Unit A – Teaching & Learning Theories

A10. Motivation

Motivation

Motivation plays a large part in students’ attention. In a study of graduate students, Sogunro (2017, p. 175) asked participants to rank eight factors in teaching and found that “quality instruction, relevance and pragmatism, and quality curriculum were the three most highly rated motivating factors,” with quality instruction being ranked highest by over 40%. Quality instruction was defined by the students as a competent instructor effectively engaging students. This means that we need to help students want to learn intrinsically, not just extrinsically through grades.

“Students will never use knowledge they don’t care about, nor will they practice or apply skills they don’t find valuable. So, another goal of the course is affective” (Rose et al., 2006, p. 139).

During the student analysis phase of course design, identify what are the students’ motivations for taking your course and for learning your subject. For example, do they have an intrinsic interest in the topic (is this their major – not that this guarantees interest) or are they taking this course as a requirement for graduation? Probably some students will fall into each category. However, if you are teaching a graduate level course or a senior-level course, your students may be more intrinsically motivated to learn.

Concepts that impact motivation:

- Cognitive load theory provides information about the ability to process information based in part on student motivation.

- UDL discusses the importance of motivation to support student attention and learning.

- Some learning outcomes such as significant learning might be impacted by student motivation.

- Load, power, & margin (A11) provides information about non-educational pressures on an individual.

(For comparisons of various motivation theories, see Park (2017), Souders (2020), or Madsen (1974).)

Motivational Outcomes & Objectives

Supiano (2021) reports that research shows a warm tone is better received by students and “makes students more likely to reach out for help.” To support this, when writing objectives, changing ‘student’ or ‘you’ to ‘we’ provides a warmer, collaborative tone.

Motivational outcomes might be worded like this:

“By the end of this course, we will be able to demonstrate the value of…”

Defining Active & Transformational Learning

Transformative learning requires higher-order cognitive ability, targeted at Bloom’s Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating steps. Examples of challenging ideas:

- Cockroaches are vital for human survival.

- The Google search engine is biased and promotes prejudices.

- Transformative learning is only applicable in liberal education.

Specific example

Outcome: By the end of this course, we will be able to demonstrate the value of Bloom’s taxonomies.

Objectives:

- By the end of this workbook, we will be able to explain why Bloom’s Taxonomies are important in designing a course.

- By the end of this workbook, we will have incorporated Bloom’s Taxonomies into their courses.

ARCS

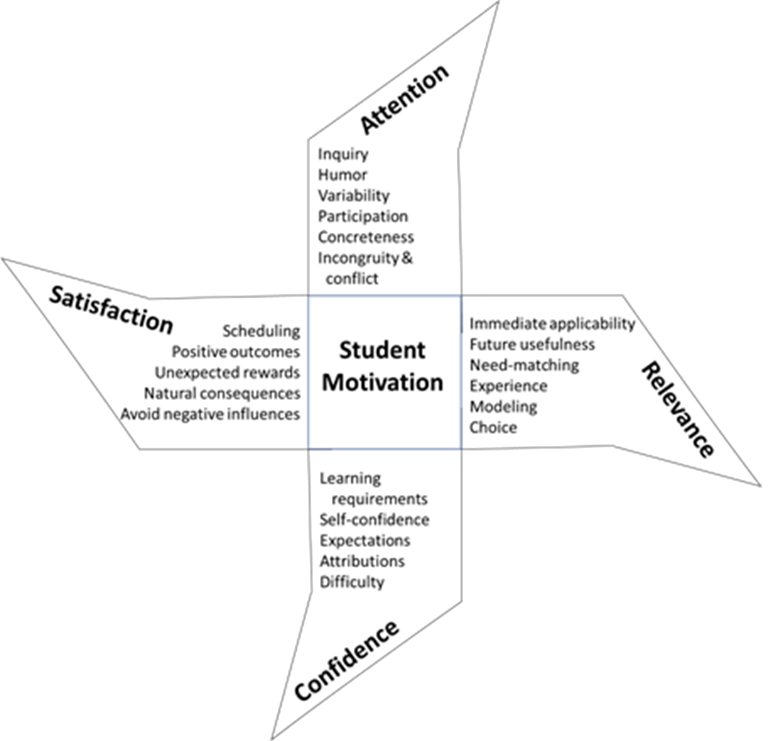

In the ARCS model, Keller (2010) identified four features in student motivation (Figure). The following are extracted from Keller (1987):

The ARCS Model defines four major conditions (Attention, Relevance, Confidence, and Satisfaction) that have to be met for people to become and remain motivated (Keller, 1987, p. 2). Attention. … As an element of learning, the concern is for directing attention to the appropriate stimuli. … Getting attention is not enough. A real challenge is to sustain it, to produce a satisfactory level of attention throughout a period of instruction. To do this, it is necessary to respond to the sensation-seeking needs of students (Zuckerman, 1971) and arouse their knowledge-seeking curiosity (Berlyne, 1965), but without overstimulating them. The goal is to find a balance between boredom and indifference versus hyperactivity and anxiety (Keller, 1987, p. 3). Relevance…. Relevance can come from the way something is taught; it does not have to come from the content itself. For example, people high in "need for affiliation" will tend to enjoy classes in which they can work cooperatively in groups. Similarly, people high in "need for achievement" enjoy the opportunity to set moderately challenging goals, and to take personal responsibility for achieving them. To the extent that a course of instruction offers opportunities for an individual to satisfy these and other needs, person will have a feeling of perceived relevance (Keller, 1987, p. 3). Confidence. There are several factors that contribute to one's level of confidence, or expectancy for success. For example, confident people tend to attribute the causes of success to things such as ability and effort instead of luck or the difficulty of the task (Weiner, 1974; Dweck, 1986). They also tend to be oriented toward involvement in the task activity and enjoy learning even if it means making mistakes. Also, confident people tend to believe that they can effectively accomplish their goals by means of their actions (Bandura, 1977; Bandura & Schunk, 1981… Fear of failure is often stronger in students than teachers realize. A challenge for teachers in generating or maintaining motivation is to foster the development of confidence despite the competitiveness and external control that often exist in schools (Keller, 1987, p. 5). Satisfaction. According to reinforcement theory, people should be more motivated if the task and the reward are defined, and an appropriate reinforcement schedule is used. Generally this is true, but people sometimes become resentful and even angry when they are told what they have to do, and what they will be given as a reward.… When a student is required to do something to get a reward that a teacher controls, resentment may occur because the teacher has taken over part of the student's sphere of control.… The establishment of external control over an intrinsically satisfying behavior can decrease the person's enjoyment of the activity (Keller, 1987, p. 6).

Keller developed a list of strategies for each step in ARCS, available in his article (Keller, 1987).

Figure: ARCS Model

Keller also identified actions to take during course design and teaching to enhance student motivation (See Table 1). Texas Tech University Worldwide eLearning (n.d.) also provides a table for applying ARCS concepts (See Table 2). Both Texas Tech University’s and Keller’s suggestions have been incorporated in the IDI worksheets.

Table 1: Steps in the ARCS Motivational Design Process (From Keller, 2010, p.6)

| STEP | ACTIONS |

|---|---|

| 1. Obtain Course information | Obtain course description & rationale Describe setting and delivery system Describe instructor information |

| 2. Obtain audience (student) information | List entry skill levels Identify attitudes toward school or work Identify attitudes toward course |

| 3. Analyze audience | Prepare motivational profile List root causes Identify modifiable influences |

| 4. Analyze Existing materials | List positive features List deficiencies or problems Describe related issues |

| 5. List objectives & assessments | List motivational design goals Specify learner behaviors Describe confirmation me1hods |

| 6. List potential tactics | Brainstorm list of A, R, C, & S tactics Identify beginning, during, end, and continuous tactics |

| 7. Select & design tactics | Integrate A, R, C, & S tactics Identify enhancement versus sustaining tactics |

| 8. Integrate with instruction | Combine motivational and instructional plans List revisions to be made |

| 9. Select & develop materials | Select available materials Modify to fit the situation Develop new materials |

| 10. Evaluate & revise | Obtain student reactions Determine satisfaction level Revise if necessary |

Table 2: Applying the ARCS Model (From Texas Tech University Worldwide eLearning, n.d.)

| Component | Subcategories | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| A Attention | Perceptual Arousal | Real-world Examples: Use related and specific examples about content. Humor: Use a small amount humor to maintain interest. (Much humor may be distracting.) Incongruity and Conflict: Go against learners’ past experiences or provide opposite point of view. |

| Inquiry Arousal | Active participation: Provide learners with hands on or role playing activities. Inquiry: Ask learners questions to allow them to do brainstorming or critical thinking. | |

| Variability | Use variety of methods and approach (e.g. videos, discussion groups, lectures, collaborate learning) to sustain interest. | |

| R Relevance | Goal Orientation | Perceived Present Worth: Explain why and how this content will help the learners today. Perceived Future Usefulness: Explain why and how this content will help the learners in the future (e.g. finding a job, getting into a college, etc.). |

| Motive Matching | Needs Matching: Assess learners to get better understanding whether they learn because of achievement, power, or affiliation. Choice: Allow learners to choose their own instructional method and strategies. | |

| Familiarity | Link to Previous Experience: Give learners a sense of continuity by allowing them to establish connections between new information and what they already know. Modeling: Show learners role models using the content that you present to improve their lives. | |

| C Confidence | Learning Requirements | Communicate Objectives and Prerequisites: Provide learners with learning standards and evaluation criteria so that they can establish positive expectations and achieve success. |

| Success Opportunities | Facilitate Self-growth: Give learners opportunity to be successful by providing multiple and varied experiences. Provide Feedback: Give learners feedback about their improvements and deficiencies during the process so that they can adjust their performance. | |

| Personal Control | Give Learners Control: Learners need to get control over their learning process so that they can feel that their success does not totally depend on external factors. Instead, they have internal factors affecting their success. | |

| S Satisfaction | Intrinsic Reinforcement | Encourage intrinsic enjoyment of learning experience so that learners have fun, continue the learning process without expecting reward or other kind of external motivational elements. |

| Extrinsic Reward | Praise or Rewards: Provide learners with positive feedback, rewards, and reinforcements. Be careful about the scheduling of reinforcement. It is more effective when you provide reinforcement at non-predictable intervals. | |

| Equity | Maintain consistent for success. Use consistent assessment rubrics, and share them with learners. |

Academic Dishonesty

A quick word about academic dishonesty (Cheating) – this is a major problem in many courses. Goldonowicz (2014, p.3) reports “92% of students from one study reported that either they or someone they knew had cheated.” Other studies have found similar results. “A number of factors have been found to influence whether students cheat, including neutralizing attitudes, perceived norms, pressures to succeed, likeliness of punishment, and moral beliefs” (Goldonowicz, 2014, p. 4).

Students rationalize dishonesty in several ways. Some students claim severe constraints on their time make cheating a sensible response. Academic entitlement is also a growing reason for cheating; students feel that they are paying for college and expect good grades in return.

“Cheating is an inappropriate response to a learning environment that’s not working for the student” (Lang, 2013). Lang states:

We can characterize some students as mastery-oriented in their learning, and some as performance-oriented. Mastery-oriented students have a real desire to learn and master the material; performance-oriented students want to do well on the assignments and exams, and are less concerned about the material for its own sake. … the design of the learning environment can nudge students toward mastery or performance orientations. The more choices and control you can give to students over how they will demonstrate their learning to you, the more you nudge them toward mastery learning. … Without question, the best means of improving student metacognition is with frequent, low-stakes assessments. Whatever you are going to ask students to do on their graded assessments, give them the opportunity to try smaller, low-stakes versions in class or on homework assignments before they have to ramp up and try for the grade.

Goldonowicz (2014, p.14) reports

Research on student motivation indicates that an effective way to motivate students to complete a goal is by increasing the students’ perceived responsibility for the consequential actions (Cheng & Hsu, 2012). When students are reminded of their personal responsibility, the pressures and interdependence with the other class members can cause the students to change their behavior (Richmond & McCroskey, 1984). Additionally, teachers are urged to create an environment that values student participation and encourages students to accept responsibility for their academic behaviors (Cohen, 1985). Cheng and Hsu’s research shows that if a student feels personally responsible for his or her performance, he or she is likely to change his or her prior attitudes in a positive way (Cheng & Hsu, 2012). Ultimately, the drive for academic success is related to how one views one’s own academic competence and need for achievement (Harmann, Widner & Carrick, 2013). Chiesl (2007) argued that to curb the occurrence of cheating in the college classroom, professors should clearly inform students that honesty is highly valued in the class. Yet, this clarification on its own is not enough. It has been found that students tend to cheat when policies are unclear and unenforced (Passow et al., 2006). Therefore, instructors need to be explicit with what is considered to be cheating (O’Rourke et al., 2010).

A recent research study, as reported by Alonso (2022), found that a combination of six interventions can help curb dishonesty:

discussing academic integrity early in the course; requiring students to achieve 100 percent on an academic integrity quiz; allowing students to withdraw assignments they may have second thoughts about handing in; reminding students about the cheating policy partway through the term; demonstrating anticheating tools, such as software that identifies similarities in completed student assignments; and normalizing academic help and support.

IDI & Motivation

The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from Motivation in the IDI model:

Step 1. Where are You Starting?

1.2 Identify Student Learning Characteristics

- Identify why your students are attending your course.

Step 2. Where are You Going?

2.1 Write Learning Outcomes & Objectives

- Identify any motivation outcomes you may want to include in your course (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

2.2 Finalize Learning Model

- Think of any motivational issues that may arise based on the selected learning model (such as how to motivate students to do readings or start a project early)

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- If you included motivation objectives in your course, determine how you will measure these.

- Consider what types of assignments might motivate students.

- Identify projects and problems that will stimulate student inquiry.

- Consider your approaches to cheating. How will you reinforce your syllabus statements about academic dishonesty?

- “Give learners feedback about their improvements and deficiencies during the process so that they can adjust their performance” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- “Allow learners to choose their own instructional method and strategies” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.). “The more choices and control you can give to students over how they will demonstrate their learning to you, the more you nudge them toward mastery learning” (Lang, 2013).

Syllabus

- “Provide learners with learning standards and evaluation criteria so that they can establish positive expectations and achieve success” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- “Use consistent assessment rubrics and share them with learners in the syllabus.” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- Be very clear about what constitutes cheating and the consequences (Goldonowicz, 2014, p.7).

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.1 Develop & Teach Course

- “Provide learners with hands on or role-playing activities” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- “Show learners role models using the content that you present to improve their lives” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- “Use variety of methods and approach (e.g. videos, discussion groups, lectures, collaborate learning) to sustain interest” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

First Day/Class

- Ask the students about their motivation for attending the course and their attitudes toward learning and the course.

- “Assess learners to get better understanding whether they learn because of achievement, power, or affiliation.” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- “Explain why and how this content help the learners in the future (e.g. finding a job, getting into a college, etc.).” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

Ongoing

- “Use related and specific examples about content.” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- “Encourage intrinsic enjoyment of learning experience so that learners have fun, continue the learning process without expecting reward or other kind of external motivational elements.” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- “Ask learners questions to allow them to do brainstorming or critical thinking” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- Use “novel or unexpected approaches to instruction or injecting personal experiences and humor” (Mi, 2015,p.1)

- “Go against learners’ past experiences or provide opposite point of view” (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- Stimulate “curiosity by asking questions or presenting problems to solve” (Mi, 2015).

- Use “a range of methods and different forms of media to meet students’ varying needs, or varying an instructional presentation” (Mi, 2015).

- Use positive feedback and rewards to motivate students.

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Brainstorm a list of tactics for motivation at the end of each class (Worldwide eLearning, n.d.).

- Use the class outline to note how various activities worked.

References

Alonso, J. (2022, November 10). Simple Interventions Can Curb Cheating, Study Finds. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2022/11/10/low-effort-interventions-can-combat-student-cheating .

Goldonowicz, J. (2014). Cognitive Dissonance in the Classroom: The Effects of Hypocrisy on Academic Dishonesty [University of Central Florida]. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5535&context=etd.

Keller, J. M. (1987). Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. Journal of Instructional Development, 10(3), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02905780.

Keller, J. M. (2010). The ARCS Model of Motivational Design. In Motivational Design for Learning and Performance. Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4419-1250-3_3.

Lang, J. M. (2013, September 11). “Cheating Lessons” (S. Golden, Interviewer) [Interview]. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/09/11/author-new-book-discusses-ways-reduce-cheating-and-improve-student-learning.

Madsen, K. B. (1974). Modern Theories of Motivation: A Comparative Metascientific Study (p. 472). John Wiley & Sons.

Mi, M. (2015). Instructional Design for Motivation. Strategies’for’Engagement, Oakland University’s Instructional Fair 2015. https://www.oakland.edu/Assets/Oakland/cetl/files-and-documents/InstructionalFair/05_Mi_Motivation_IF2015.pdf.

Park, S. W. (2017). Motivation Theories and Instructional Design. In Foundations of Learning and Instructional Design Technology. https://lidtfoundations.pressbooks.com/chapter/motivation-in-lidt-by-seungwon-park/.

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal Design for Learning in Postsecondary Education: Reflections on Principles and their Application. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19(2), 135–151.

Sogunro, O. A. (2017). Quality Instruction as a Motivating Factor in Higher Education. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(4), 173–184.

Souders, B. (2020, January 7). Motivation in Education: What it Takes to Motivate Our Kids. PositivePsychology.Com. https://positivepsychology.com/motivation-education/.

Supiano, B. (2021, March 25). Teaching: How Your Syllabus Can Encourage Students to Ask for Help. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2021-03-25.

Worldwide eLearning. (n.d.). ARCS Model of Motivation. Texas Tech University. http://www.tamus.edu/academic/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2017/07/ARCS-Handout-v1.0.pdf.