Unit A – Teaching & Learning Theories

A3. Active & Transformative Learning

- Active & Transformative Learning

- Active Learning

- Transformative Learning

- Research On Active Learning

- Covering the Material vs Active and Transformative Learning

- Can Online Learning be Active?

- Assessing Transformative & Active Learning

- Identifying Transformative Outcomes For Your Course

- Helping Students Through Their Transformations

- IDI & Active & Transformative Learning

- References

Active & Transformative Learning

“For over 30 years, research has shown that higher education students learn more and better when they are actively engaged with the material, the instructor, and their classmates” (Howard, 2019, p. 4). Lu et al (2021, p. 9) provide some rationale for this: “In a student-centered class, students no longer only rely on their instructor to give them instructions. Instead, students actively communicate, collaborate, and learn from each other, as well as apply and improve their critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity skills.”

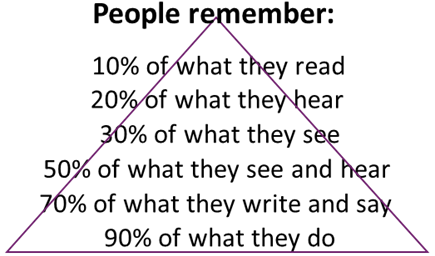

While you cannot force students to learn, you can provide the environment, expectation, and activities to support learning (Marín, 2022). The cone of learning (See Figure), attributed to a wide variety of people, is based on old adages that we learn more by doing than hearing. If we want our learners to truly learn, we need to get them involved in the learning.

Figure: Cone of Learning

NOTE: While intuitively most people would agree that the levels, if not the percentages, are right, this model is not proven, and the numbers are made up! This is based on old sayings from various cultures, so while it may ‘ring true’, please do not take it as actual research. Many websites are dedicated to explaining the origins of this mythical model (if interested, Google “cone of learning”). I share it here because it illustrates clearly how interacting with the learning material impacts how well people learn it.

Defining Active & Transformational Learning

Active and transformational learning result in students’ deeper understanding. This may involve changes in the students’ beliefs. Although some people use the terms synonymously, here we refer to them as related but not identical: All transformative learning is active learning. Not all active learning is transformational. This does not mean active learning is not valuable; “There is extensive evidence that active learning works better than a completely passive lecture” (Eddy et al., 2015, art. abstract).

The Practical Observation Rubric To Assess Active Learning (PORTAAL) project results provide some researched recommendations on increasing both participation and the quality of participation in class discussions (Eddy et al., 2015 – available at PORTAAL).

Active learning [emphasis added] is generally defined as any instructional method that engages students in the learning process. In short, active learning requires students to do meaningful learning activities and think about what they are doing… The core elements of active learning are student activity and engagement in the learning process. Active learning is often contrasted to the traditional lecture where students passively receive information from the instructor (Prince, 2004, p. 1).

“We have defined the core elements of active learning to be introducing activities into the traditional lecture and promoting student engagement” (Prince, 2004, p. 3). The goal of these activities is to promote deeper or higher-level learning.

The term ‘active learning’ is contrasted with ‘passive learning.’ “Active learning requires students to think, discuss, challenge, and analyze information. Passive learning requires learners to absorb, assimilate, consider, and translate information” (Russell, 2021).

In a lecturing course, some students may have a few ‘Aha’ moments, but these are because the student is internally motivated to be interested and listen carefully. The student has created their own learning environment.

Mezirow defines transformative learning as “the process of effecting change in a frame of reference” (1997, p. 5). Transformative learning involves students in actively thinking about the subject and how a particular concept fits within other concepts. It challenges students’ schema and, possibly, their epistemological beliefs. While some people define transformative learning as learning that involves deep learning, others define it as learning targeted at major changes in a student’s worldview. For example, Simsek (2012, p. 3341) defines transformative learning as “the kind of learning that results in a fundamental change in our worldview as a consequence of shifting from mindless or unquestioning acceptance of available information to reflective and conscious learning experiences that bring about true emancipation.”

Active Learning

Active learning can be seen as a process and as a result. The desired result is that students become more interested in the subject and involved in higher-order learning/deeper learning about the subject. The process involves using activities such as think-pair-share, long-term group projects, and journaling.

What Active Learning Is NOT

- It is not activity for activity’s sake. Active learning is purposeful activity. It involves using thoughtfully chosen activities that will support learners at various levels of Bloom’s taxonomies.

- Active learning is different from providing students with slinkies or squeeze balls while you lecture. Yes, research has shown that keeping the hands busy can support listening longer. However, while providing fidgets helps the learner listen, it is supporting passive learning, not active or transformative learning. It also may be distracting for students.

For a fuller description of active vs passive learning, refer to Petress (2008).

Measuring Activity

One good tool for measuring how student activity is built into a course is the PORTAAL rubric, designed based on research for large STEM courses. “This tool identifies 21 readily implemented elements that have been shown to increase student outcomes related to achievement, logic development, or other relevant learning goals with college-age students. Thus, this tool both clarifies the research-supported elements of best practices for instructor implementation of active learning in the classroom setting and measures instructors’ alignment with these practices” (Eddy et al., 2015, art. abstract).

Transformative Learning

Transformational learning changes the student mental schema and some TCs may be transformational. Mezirow (1997, p.5) explained the need for transformative learning: “In contemporary societies we must learn to make our own interpretations rather than act on the purposes, beliefs, judgments, and feelings of others. Facilitating such understanding is the cardinal goal of adult education. Transformative learning develops autonomous thinking.” It challenges students’ schema (see Chapter A2) and, possibly, their epistemological beliefs (Chapter A7) . Some of these challenges will be relatively minor, such as understanding opportunity cost in project management (See Table 2). Some courses such as countering bias in the workplace may have challenges which are more difficult for the students to identify in themselves (such as their own biases) or to understand (such as how diversity can increase project quality).

Transformative Learning and Taxonomies

Transformative learning requires higher-order cognitive ability, targeted at Bloom’s Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating steps. Examples of challenging ideas:

- Cockroaches are vital for human survival.

- The Google search engine is biased and promotes prejudices.

- Transformative learning is only applicable in liberal education.

The Transformative Learning Process

For students to change schema, they go through a process where they find something that differs from what they expect. They are first challenged with an idea. This may trigger an examination of their current belief about the idea with an examination of the consequences of accepting the new idea.

In major transformations, an action plan may be developed to analyze the new idea, including research into the validity of their old schema and the new idea. If the idea is contrary to their current beliefs (such as the benefits of family-centered cultures), the students may reject the idea or take a while to accept it and adjust their schema.

Sometimes a challenging idea may result in an ‘Ah-ha!’ moment – a paradigm shift. However, many times the shift is slow as more information is gathered that confirms the idea.

Transformative learning requires a change in mental schema (see Chapter A2).

For more on research in transformative learning, see the Journal of Transformative Learning.

Research On Active Learning

Although many instructors are most comfortable with a lecture-based method of teaching, research shows that this is not usually the most effective learning method for students. Instead, active and transformative learning have been proven to be more effective for both depth and breadth of learning.

Most learning theories talk about the importance of student activity in the learning process. Each theory requires that students change in order to grow. Change requires active participation.

The National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) has examined over 1600 colleges and universities and found that hands-on, integrative, and collaborative active learning experiences lead to high levels of student achievement and personal development (McCarthy, 2009).

The Purdue University IMPACT Program, which started in 2011, reports student success improvements and reports high decreases in D, F, or withdraw rates. Faculty attending the program consistently report that the results of attending the IMPACT program are sustainability and transferability. At the same time, FitzSimmons (2018) reports “IMPACT Fellows report:

- Significant increases in teaching satisfaction

- Significant improvements in pedagogical practices

- Significant increases in observed student engagement

- Significant improvements in experiences teaching in classroom learning spaces

For more information on the IMPACT project, including annual reports, presentations, and publications, see IM:PACT.

Other programs report similar results:

MDRC (2015) found that while ASAP [CUNY's Accelerated Study in Associate Programs] cost about 60 percent more overall compared with how the college typically provided instruction and support services, many more ASAP students completed their degree, making it more cost-effective than the college's ‘business as usual’ model. The ASAP program reduced the cost of graduating a student by 11 percent (Kuh et al., 2017, p. 13).

Covering the Material vs Active and Transformative Learning

It is rare that straight lecturing is either active or transformative.

Lecturing induces passivity of thought, even in the best of students. They hurriedly take notes, but have little time to reflect on or question the material being jotted down… Lecturing doesn’t always encourage students to move beyond memorization of the information presented to analyzing and synthesizing ideas so that they can employ them in new ways (Center for Teaching and Learning, Stanford University Newsletter on Teaching, 1993).

However, “there is always the pressure to cover more and more material, so that activities involving students–activities taking up classroom time–seem wasteful” (Center for Teaching and Learning, Stanford University Newsletter on Teaching, 1993).

Instructors who are interested in providing their students with active and/or transformative learning experiences must balance the pressures of ‘covering’ material with the pressures of identifying, designing, and managing learning to meet active and/or transformative learning outcomes. Well-designed courses can accomplish both but must start with careful consideration of learning outcomes.

One frequently used method for managing this, referred to as flipping, focuses on moving the content outside of the class sessions and using the classes to provide the transformative learning experiences (using models such as problem-, project-, team-based learning models, etc.).

Large Classes & Active Learning

While you may think that it may be more difficult to incorporate activities in large classes, active learning techniques are even more important in a class where students can ‘tune out.’

Instructors in the Purdue IMPACT program have focused on turning large classes (between 50 and 120 students) into interactive and transformative courses. This has included using the following learning structures:

- Problem-Based Learning

- Case-Based Learning

- Project-Based Learning

- Flipped courses

(For information about course structures, see B3.)

However, even traditional lecture-based courses can incorporate active and transformative learning. One instructor was teaching Excel to a large group of students in a lecture hall where he had the only computer (it was projected). To support student learning, he asked the students to come up with formulas in pairs, then share them with the class. Also, he asked many short-answer questions and tossed candy to the answerers (whether right or wrong). To move from active to transformative learning, he had students participate in think-pair-share activities and the homework was team-based project work where students were given a case study to build Excel spreadsheets to solve the case.

The Center for Teaching and Learning, Stanford University Newsletter on Teaching (1993) also suggests:

Several techniques are possible with large classes: lecture for thirty minutes or so, and spend the final time asking questions that require students to apply what they’ve heard, or analyze it, or relate it to their reading assignments; punctuate lectures with brief questions that require students to explain major concepts with examples or analogies; use one class a week solely for discussion, so that students come prepared to participate.

Specific group projects can be assigned that require groups to meet outside of class. Groups might be responsible for starting discussion, for presenting important concepts, or reporting on research. To generate discussion, groups can be told to research a complex issue and in class be asked to represent a specific position in an impromptu debate.

Huglin (2014) compiled a list of 12 large group learning strategies:

- Just‐in‐Time‐Teaching

- Peer‐Reviewed Research Assignments

- Group Projects/Mini‐conference

- Collaborative Learning Groups (CLGs)

- Concept Mapping

- Group Folders

- Learning Cycle Instructional Models (5E)

- Student Presentations of the Literature

- Jigsaw

- Fishbowl

- Problem‐Based Learning/Case Studies

- Think/Pair/Share

Descriptions for each are available here Active Learning Strategies for Large Group Instruction.

Lecture & Active Learning

Active and transformative learning can be incorporated into a course by:

- Including interaction during lectures or

- Adding assignments which are more thought-provoking

1. Including Interaction During Lectures

Students are least likely to be involved in transformative learning when they are passively listening to a lecture or watching a video. You can incorporate transformative learning into lectures and videos to increase student learning. This can be as simple as using the ‘bookend’ lecturing method described in Chapter C6. You can add more interactivity by introducing activities that help students analyze, synthesize, and evaluate the information described in Chapter C7.

2. Adding Activities & Assignments Which Are More Transformative

Transformative learning occurs when the students are thinking deeply about the new material, so many activities and assignments can involve transformative learning. Some learning models provide a framework specifically designed for transformative learning.

- When considering activities and assessments think through what you will do with the completed work. For example, will you provide personalized feedback on each activity, or be responding to each student’s “Muddiest point” or “Minute paper” (described in Angelo & Cross, 1993), will you group or pair students to discuss their responses, collect the responses and use for future course sessions, etc.?

- Group work assignments have major advantages over individual assignments and are frequently defined as a high-impact practice as research has shown that students learn from each other. These can be just requiring students to group together to do homework or take quizzes, or projects which require multiple group meetings. Group assignments can be during or outside of class time. Collaborative work could include:

- Peer tutoring

- Class debates

- Class discussions

- Student- or group-led lessons

- Role plays

- Case studies

- Team assignments

- Team assessments

In Chapter C7: Assessments & Activities, you can find a list of possible formative and summative assessments. Chapter C11 has information about managing group work.

Can Online Learning be Active?

With the advances in technology and the new online experiences of instructors (ex.: teaching during the pandemic), many learning models incorporate online learning and a course which is fully online can now incorporate many features of the models. For example, it is possible to use a Case-Based or Project-Based Learning model in a fully online course. Online courses can be just as active as classroom-based courses. For descriptions of some approaches, see Teaching Tools: Active Learning while Physically Distancing 2.0.

The chart in Chapter B3 of learning models which compares the models does not include classroom-based vs online except where the model specifically requires one or the other.

Assessing Transformative & Active Learning

Most frequently, transformative and active learning requires work that is difficult to measure with multiple choice tests. Instead, a rubric can focus on “evidence of critical reflection in terms of content, process and premise. Content reflection consists of curricular mapping from student and faculty perspectives; process reflection focuses on best practices, literature-based indicators and self-efficacy measures; premise reflection would consider both content and process reflection to develop recommendations” (Culatta, n.d.).

Examples of rubrics are available at the AAC&U VALUE site (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE), n.d.)

Identifying Transformative Outcomes For Your Course

To help identify active and transformational outcomes, review AAC&U’s Goals of Liberal Education, Fink’s Significant Learning categories and the Angelo & Cross Teaching Goals Inventory, (53 Likert-scale questions, available free here: Teaching Goals Inventory and Self-scoring inventory).

AAC&U’s Goals of Liberal Education

The American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) sponsored research into learning goals for twenty-first-century challenges (Kuh et al., 2008, p. 4) (Skip):

Beginning in school, and continuing at successively higher levels across their college studies, students should prepare for twenty-first-century challenges by gaining: Knowledge of Human Cultures and the Physical and Natural World • Through study in the sciences and mathematics, social sciences, humanities, histories, languages, and the arts Focused by engagement with big questions, both contemporary and enduring Intellectual and Practical Skills, including • Inquiry and analysis • Critical and creative thinking • Written and oral communication • Quantitative literacy • Information literacy • Teamwork and problem solving Practiced extensively, across the curriculum, in the context of progressively more challenging problems, projects, and standards for performance Personal and Social Responsibility, including • Civic knowledge and engagement—local and global • Intercultural knowledge and competence • Ethical reasoning and action • Foundations and skills for lifelong learning Anchored through active involvement with diverse communities and real-world challenges Integrative and Applied Learning, including • Synthesis and advanced accomplishment across general and specialized studies Demonstrated through the application of knowledge, skills, and responsibilities to new settings and complex problems

The research project then identified high-impact practices (HIPs) that support these goals:

- Capstone Courses and Projects

- Collaborative Assignments and Projects

- Common Intellectual Experiences

- Diversity/Global Learning

- ePortfolios

- First-Year Seminars and Experiences

- Internships

- Learning Communities

- Service Learning, Community-Based Learning

- Undergraduate Research

- Writing-Intensive Courses

Although some of these are specific to institute-wide or program initiatives rather than courses, some can be course-level projects.

For details on these HIPS, see Kuh et al., 2017, Kuh et al., 2008 and the AAC&U website High-Impact Practices (High-Impact Practices, n.d.).

Fink’s Significant Learning

Fink developed a taxonomy of 6 dimensions of learning that can be useful when considering transformative learning. Fink uses the term Significant Learning which he defines as requiring “that there be some kind of lasting change that is important in terms of the learner’s life” (Fink, n.d., p. 3).

Fink’s taxonomy is not hierarchical; it is relational and interactive. This is illustrated as a Venn diagram to emphasize the interrelatedness and importance of all aspects to achieve significant learning (Figure 3, from Fink, 2013, p.33.).

- Foundational Knowledge

- (Understanding and remembering ideas and information)

- Application

- (Skills, thinking, and managing projects)

- Integration

- (Connecting ideas, people, realms of life)

- Human Dimension

- (Learning about oneself and others)

- Caring

- (Developing new feelings, Interests, and/or values)

- Learning How to Learn

- (Becoming a better student, seeking more about a subject, becoming a self-directed learner)

For definitions of these, see Fink (n.d., p. 4).

Angelo & Cross’s Teaching Goals

Angelo and Cross (1993, p. 13) developed the Teaching Goals Inventory (53 Likert-scale questions, available free here: auto-calculated inventory and self-scoring inventory) targeted at helping HE instructors “identify and rank the relative importance of their teaching goals.” “The Teaching Goals Inventory (TGI) is a self-assessment of instructional goals. Its purpose is threefold: (1) to help college teachers become more aware of what they want to accomplish in individual courses; (2) to help faculty locate Classroom Assessment Techniques they can adapt and use to assess how well they are achieving their teaching and learning goals; and (3) to provide a starting point for discussions of teaching and learning goals among colleagues” (Angelo & Cross, 1993, p. 20).

They also identified 50 assessment techniques (CATS) for each sub-area. (For a spreadsheet listing CATS by teaching goal, see https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1NAIxhpdmS0MVONw6Zzb9kutBdBouGhM8w4CqFLFlTDI/edit?usp=sharing)

Table: Angelo & Cross’s Teaching Goals

| Angelo & Cross’s Teaching Goals |

|---|

| Cluster 1: Higher-Order Thinking Skills |

| Cluster 2: Basic Academic Success Skills |

| Cluster 3: Discipline Specific Knowledge & Skills |

| Cluster 4: Liberal Arts & Academic Values |

| Cluster 5: Work & Career Preparation |

| Cluster 6: Personal Preparation |

Helping Students Through Their Transformations

To help students move through challenging ideas, Harbecke (2012) suggests asking students the following:

- A disorientating dilemma.

- How do you picture the event.

- Self-examination of affect (guilt, shame, etc.).

- What are you aware of feeling? Describe it. (“It’s like…”)

- Critical assessment of assumptions.

- What does it mean to you to feel this?

- What advice are you giving yourself in the picture?

- How do you interpret what is happening?

- What is your intention?

- Exploration of new roles.

- How would you prefer this to be different? (Frame and Action)

- When this begins to occur for you, even a little bit, what will be different about you?

- Planning a course of action.

- What are you aware of that keeps this from happening?

- Describe the dangers to change.

- Describe the benefits of staying the same.

- Do you act on the changes now? What’s different at those times?

- Acquiring knowledge and skills for implementation.

- What will you need to know/accomplish/overcome for this to occur (more often)?

- Trying out new roles.

- How will you know when you are more on track?

Instructors may, therefore, need to consider Bloom’s affective taxonomy when selecting strategies.

IDI & Active & Transformative Learning

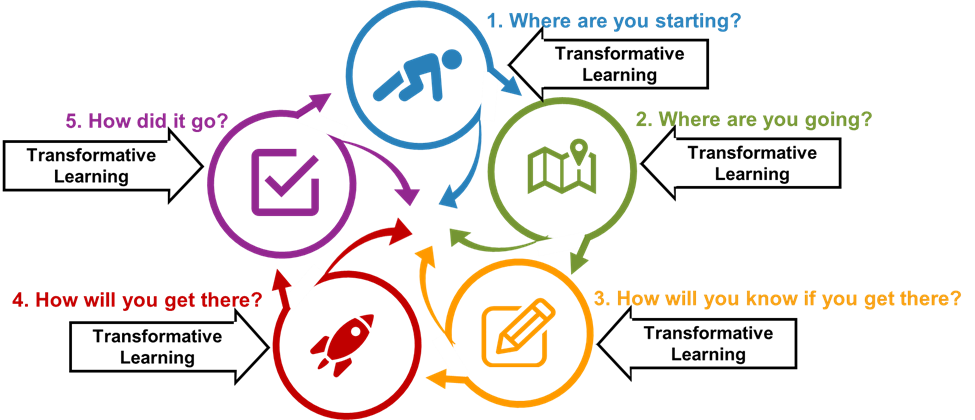

The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from transformative learning in the IDI model:

Step 1. Where are You Starting?

1.1 Review Course Requirements

- Check if your program committee identified any transformative concepts that you need to consider.

- Review AAC&U’s Goals of Liberal Education, Fink’s Significant Learning categories and the Angelo & Cross Teaching Goals Inventory to identify additional goals.

1.2 Identify Student Learning Characteristics

- Consider how might the student characteristics impact their mental models – epistemological level (Chapter A7), mental schemas and ability to accept threshold concepts (Chapter A2), etc.? How might this impact their ability to accept each transformative concept?

- Identify supports available based on possible student needs.

Step 2. Where are You Going?

2.1 Write Learning Outcomes & Objectives

- Based upon your student demographics, experience teaching, and course goals, determine what transformative learning outcomes you have for your course.

- Write your learning outcomes and objectives.

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- Determine how you will measure the achievement of each transformative outcome – this may be at the objectives level.

- Develop assessments and activities and map to outcomes and taxonomies.

- Add student support services to the syllabus.

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.1 Develop & Teach Course

- Review assessments to determine if any activities need to be included in the class outline for this class session.

- When presenting TCs and other potentially transformative concepts, use Harbecke’s (2012) discussion questions.

- Provide a copy of the class outcomes and/or objectives to your students for each session.

- Remind students of support services.

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Review all class outlines for themes relating to your course outcomes.

- Use the class outline to note how various activities worked.

References

Angelo, T., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Angelo, T., & Cross, K. P. (n.d.). Teaching Goals Inventory, Self-Scorable Version. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from http://www.tusculum.edu/adult/learning/docs/TeachingGoalsInventory.pdf

Center for Teaching and Learning, Stanford University Newsletter on Teaching. (1993, FALL). Active Learning: Getting Students to Work and Think in the Classroom. Speaking of Teaching, 5(1). https://studylib.net/doc/8109039/getting-students-to-work-and-think-in-the-classroom.

Cross, K. P., & Angelo, T. (1988). Classroom Assessment Techniques. A Handbook for Faculty. http://eric.ed.gov/?q=ED317097&id=ED317097.

Culatta, R. (n.d.). Transformative Learning (Jack Mezirow). InstructionalDesign.Org. Retrieved June 4, 2022, from https://www.instructionaldesign.org/theories/transformative-learning/.

Eddy, S. L., Converse, M., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2015). PORTAAL: A Classroom Observation Tool Assessing Evidence-Based Teaching Practices for Active Learning in Large Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Classes. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(2), ar23. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-06-0095.

Fink, L. D. (n.d.). What Is ”Significant Learning”? https://www.wcu.edu/WebFiles/PDFs/facultycenter_SignificantLearning.pdf.

FitzSimmons, J. (2018, September 19). IM:PACT Program Outcomes. Purdue University IM:PACT Program. https://www.purdue.edu/impact/outcomes/.

Harbecke, D. (2012, October 8). Following Mezirow: A Roadmap through Transformative Learning. RU Training @ Roosevelt University in Chicago. https://rutraining.org/2012/10/08/following-mezirow-a-roadmap-through-transformative-learning/.

High-Impact Practices. (n.d.). AAC&U. Retrieved July 2, 2022, from https://www.aacu.org/trending-topics/high-impact.

Howard, J. (2019, May 23). How to Hold a Better Class Discussion. CHE. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-hold-a-better-class-discussion/.

Huglin, L. (2014). Active Learning Strategies for Large Group Instruction. Boise State University. https://drive.google.com/file/d/16Ivl9nOZsJYxMWaFC6MEqeLwo16hQCxj/view.

Kuh, G., O’Donnell, K., & Schneider, C. G. (2017). HIPs at Ten. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 49(5), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2017.1366805.

Kuh, G., Schneider, C. G., & Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Association of American Colleges and Universities. https://archive.org/details/highimpacteducat0000kuhg.

Lu, K., Yang, H. H., Shi, Y., & Wang, X. (2021). Examining the key influencing factors on college students’ higher-order thinking skills in the smart classroom environment. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-020-00238-7.

Marín, V. I. (2022). Student-centred learning in higher education in times of Covid-19: A critical analysis. Studies in Technology Enhanced Learning. https://doi.org/10.21428/8c225f6e.be17c279.

McCarthy, S. A. (2009). Online learning as a strategic asset. volume I: A resource for campus leaders. a report on the online education benchmarking study conducted by the APLU-Sloan national commission on online learning. Association of Public and Land-grant Universities. 1307 New York Avenue NW Suite 400, Washington, DC 20005-4722. Tel: 202-478-6040; Fax: 202-478-6046; https://eric.ed.gov/?q=Online+learning+as+a+strategic+asset.+author%3amccarthy+volume+I&id=ED517308.

Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1997(74), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401.

Petress, K. (2008). What Is Meant by “Active Learning?” Education, 128(4), 566–569.

Prince, M. (2004). Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x.

Reid, P. (n.d.). CAT Cross-ref to Goals. Google Docs. Retrieved July 7, 2022, from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1NAIxhpdmS0MVONw6Zzb9kutBdBouGhM8w4CqFLFlTDI/edit?usp=sharing.

Russell, K. (2021, June 2). Active vs. Passive Learning: What’s the Difference? Graduate Programs for Educators. https://www.graduateprogram.org/2021/06/active-vs-passive-learning-whats-the-difference/.

Salim, Z. (2020). Active Learning while Physically Distancing 2.0. The Aga Khan University. Licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA. This work is a derivative of Baumgartner, J. et. al. (2020). Active Learning while Physical Distancing. Louisiana State University. Also licensed under CC-BY-NC-SA. Available at: https://docs.google.com/document/d/16PpcXB5Z9e8WiFwYcIMfFLv2BQidY-GzC22VXttzonk/edit

Simsek, A. (2012). Transformational Learning. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning (pp. 3341–3344). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_373.

teaching@uiowa.edu. (n.d.). Teaching Goals Inventory | Office of Teaching, Learning & Technology. Office of Teaching, Learning, & Technology, University of Iowa. Retrieved July 2, 2023, from https://tgi.its.uiowa.edu/

Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE). (n.d.). AAC&U. Retrieved June 26, 2022, from https://www.aacu.org/initiatives/value.