B. Learning & Instructional Design Principles

B1. Learning Principles

Learning Principles

“Researchers from various scientific communities have identified some principles of learning that are supported by empirical evidence and learning theories” (Graesser, 2011). Graesser et al. (2007) identified 25 learning principles and their implications for course design. Short descriptions (from Graesser, 2010) of these are:

- Contiguity Effects. Ideas that need to be associated should be presented contiguously in space and time.

- Perceptual-motor Grounding. Concepts benefit from being grounded in perceptual motor experiences, particularly at early stages of learning.

- Dual Code and Multimedia Effects. Materials presented in verbal, visual, and multimedia form richer representations than a single medium.

- Testing Effect. Testing enhances learning, particularly when the tests are aligned with important content.

- Spacing Effect. Spaced schedules of studying and testing produce better long-term retention than a single study session or test.

- Exam Expectations. Students benefit more from repeated testing when they expect a final exam.

- Generation Effect. Learning is enhanced when learners produce answers compared to having them recognize answers.

- Organization Effects. Outlining, integrating, and synthesizing information produces better learning than rereading materials or other more passive strategies.

- Coherence Effect. Materials and multimedia should explicitly link related ideas and minimize distracting irrelevant material.

- Stories and Example Cases. Stories and example cases tend to be remembered better than didactic facts and abstract principles.

- Multiple Examples. An understanding of an abstract concept improves with multiple and varied examples.

- Feedback Effects. Students benefit from feedback on their performance in a learning task, but the timing of the feedback depends on the task.

- Negative Suggestion Effects. Learning wrong information can be reduced when feedback is immediate.

- Desirable Difficulties. Challenges make learning and retrieval effortful and thereby have positive effects on long-term retention.

- Manageable Cognitive Load. The information presented to the learner should not overload working memory.

- Segmentation Principle. A complex lesson should be broken down into manageable subparts.

- Explanation Effects. Students benefit more from constructing deep coherent explanations (mental models) of the material than memorizing shallow isolated facts.

- Deep questions. Students benefit more from asking and answering deep questions that elicit explanations (e.g., why, why not, how, what-if) than shallow questions (e.g., who, what, when, where).

- Cognitive Disequilibrium. Deep reasoning and learning is stimulated by problems that create cognitive disequilibrium, such as obstacles to goals, contradictions, conflict, and anomalies.

- Cognitive Flexibility. Cognitive flexibility improves with multiple viewpoints that link facts, skills, procedures, and deep conceptual principles.

- Goldilocks Principle. Assignments should not be too hard or too easy, but at the right level of difficulty for the student’s level of skill or prior knowledge.

- Imperfect Metacognition. Students rarely have an accurate knowledge of their cognition so their ability to calibrate their comprehension, learning, and memory should not be trusted.

- Discovery Learning. Most students have trouble discovering important principles on their own, without careful guidance, scaffolding, or materials with well-crafted affordances.

- Self-regulated Learning. Most students need training on how to self-regulate their learning and other cognitive processes.

- Anchored Learning. Learning is deeper and students are more motivated when the materials and skills are anchored in real world problems that matter to the learner.

Graesser et al. (2007) provide definition, implications for teaching, and references for each of these in a 13-page document found here: https://louisville.edu/ideastoaction/-/files/featured/halpern/25-principles.pdf.

Contiguity, Repetition, Reinforcement, & Social-Cultural

According to Gagné et al. (2005, p.5-6), instructors can impact learning using four basic principles: contiguity, repetition, reinforcement, and the social-cultural environment. The first three of these, contiguity, repetition, and reinforcement, are included in the above list of 25 principles. Repetition and reinforcement defined by Gagné et al. are equivalent to a combination of several of the above principles (such as 5, 8, 10, and 11). However, social-cultural principles may be missing from the list of 25.

Social-Cultural Principles of Learning

This consists of three concepts:

Negotiated meaning – creating group work where students learn from each other and/or knowledgeable others. This is partially covered in Grasser’s Cognitive Flexibility principle.

Situated cognition – “learning [that] occurs in authentic contexts where it can be meaningfully applied is more likely to be remembered and recalled when needed” (Gagné et al., 2005, p.6). This is a combination of Graesser’s Anchored Learning, Cognitive Flexibility, Discovery Learning, and Multiple Examples principles.

Active theory – learning requires activity: mental, emotional, and/or physical (see Chapter A6). This is partially included in the following principles from Grasser: Generation Effect, Perceptual-motor Grounding, Dual Code and Multimedia Effects, Manageable Cognitive Load, Organization Effects, Feedback Effects, and Deep questions.

UDL Principles

CAST, a nonprofit education research and development organization targeted at reducing barriers to learning, developed a set of 4 principles called Critical Elements of UDL (Universal Design for Learning) (CAST, n.d.). Although these align somewhat with Graesser’s principles, Graesser’s principles do not completely fill the UDL principle (See Table).

Table: Matching UDL & Grasser Principles

| UDL Principle | Matching Graesser Principle |

|---|---|

| Clear goals | Coherence Effect, Testing Effect |

| Intentional Planning for Learner Variability | Stories and Example Cases |

| Flexible Methods and Materials | Dual Code and Multimedia Effects, Cognitive Flexibility, Discovery Learning |

| Timely Progress Monitoring | Testing Effect, Spacing Effect, Feedback Effects, Negative Suggestion Effects |

Goals, Outcomes & Objectives

Goals, outcomes, and objectives are frequently singled out and emphasized in course design because they inform the rest of the design and development process. For this reason, a major portion of many books on ID have multiple chapters about writing outcomes and objectives and several authors have written books just on outcomes and objectives (see Kennedy, 2006; Mager, 1997; Popenici et al., 2015 for examples).

Learning outcomes or learning objectives and learning goals – Unfortunately, the definitions for learning goals, outcomes, and objectives are not universal across universities or even within a campus. This workbook uses the following definitions (details on writing these – Chapter C2 and worksheets 2.1a, 2.1b, and 2.1c):

- Program Goals refer to the large purpose for your course. These may be defined by your program or accreditation association.

- Learning outcomes refer to the large or overarching goals you have for your course. These may be the same as the program goals or may be more finite. They may also include outcomes you would like to see in students that are not in the program goals.

- Learning objectives – Here, we use this term to mean the more concrete or specific goals which make up a learning outcome. So, for each learning outcome, you likely will have several learning objectives.

Learning theorists have found that sharing course outcomes and objectives with students helps the students understand context for new information and motivates them to learn (Gagné et al., 2005; Keller, 1987; Russell & Morrow, 1999; Svinicki & McKeachie, 2014).

See Chapter C2 for details on identifying and writing outcomes and objectives. Note that many of the principles here also approach inclusivity and diversity.

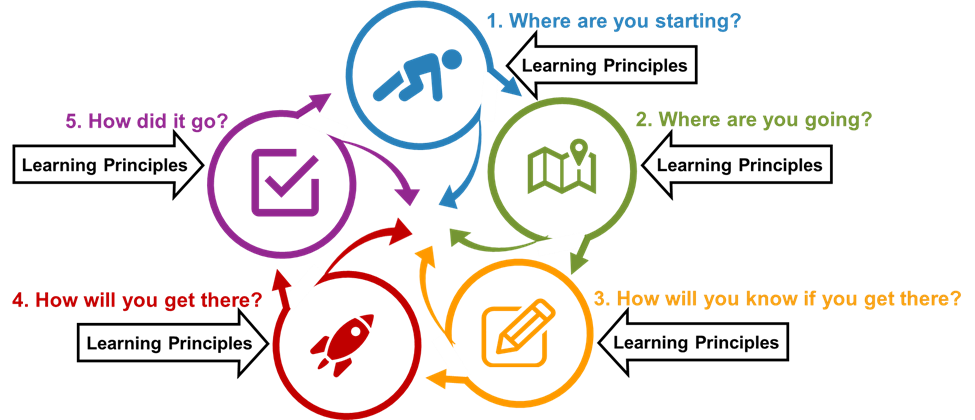

IDI & Learning Principles

The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from Learning Principles in the IDI model:

Step 1. Where are You Starting?

1.1 Review Course Requirements

- Work with Student Disability Services to proactively identify students who might need additional considerations.

Step 2. Where are You Going?

2.1 Write Learning Outcomes & Objectives

- Teach students “how to self-regulate their learning and other cognitive processes” (Graesser, 2010, p. 22).

- Provide clear individual goals through SMART objectives (CAST, n.d.).

2.2 Finalize Learning Model

- Work with Student Disability Services to proactively identify how specific learning models provide learner variability within your discipline (CAST, n.d.).

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- “Testing enhances learning, particularly when the tests are aligned with important content” (Graesser, 2010, p. 18).

- “Spaced schedules of studying and testing produce better long-term retention than a single study session or test” (Graesser, 2010, p. 18).

- “ Students benefit more from repeated testing when they expect a final exam” (Graesser, 2010, p. 19).

- “Learning is enhanced when learners produce answers compared to having them recognize answers” (Graesser, 2010, p. 19).

- “Assignments should not be too hard or too easy, but at the right level of difficulty for the student’s level of skill or prior knowledge” (Graesser, 2010, p. 22).

- “Students rarely have an accurate knowledge of their cognition so their ability to calibrate their comprehension, learning, and memory should not be trusted” (Graesser, 2010, p. 22).

- “Learning [that] occurs in authentic contexts where it can be meaningfully applied is more likely to be remembered and recalled when needed” (Gagné et al., 2005, p.6).

- Provide assessment variety and options for Flexible Methods and Materials to support Learner Variability and learner growth (CAST, n.d.).

- Include course outcomes and objectives in the syllabus.

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.1 Develop & Teach Course

- Use group work where students learn from each other and/or knowledgeable others (Gagné et al. 2005, p.5-6)

- Include psychomotor activities, particularly at early stages of learning (Graesser, 2010, p. 18). (Gagné et al., 2005, p.6).

- Use stimulating activities to increase motivation and challenge their thinking to encourage long-term retention and help them want to pay attention, which will decrease cognitive load (Graesser, 2010, p. 21).

- Provide guidance and scaffolding to help students discover important principles on their own (Graesser, 2010, p. 22).

- Create cognitive disequilibrium, such as obstacles to goals, contradictions, conflict, and anomalies, to encourage use of HOTS to solve problems (Graesser, 2010, p. 21).

- Provide assessment variety and options for flexible methods and materials to support Learner Variability and learner growth (CAST, n.d.).

- Share course outcomes and objectives for each unit.

- “Ideas that need to be associated should be presented contiguously in space and time (Graesser, 2010, p. 18).

- “Materials and multimedia should explicitly link related ideas and minimize distracting irrelevant material (Graesser, 2010, p. 19).

- “An understanding of an abstract concept improves with multiple and varied examples (Graesser, 2010, p. 20).

- “The information presented to the learner should not overload working memory (Graesser, 2010, p. 20).

- “A complex lesson should be broken down into manageable subparts (Graesser, 2010, p. 21).

- “Outlining, integrating, and synthesizing information produces better learning than rereading materials or other more passive strategies” (Graesser, 2010, p. 19).

- “Stories and example cases tend to be remembered better than didactic facts and abstract principles” (Graesser, 2010, p. 19).

- “Learning is deeper and students are more motivated when the materials and skills are anchored in real world problems that matter to the learner” (Graesser, 2010, p. 22).

4.2 Assess Students

- “Students benefit from feedback on their performance in a learning task, but the timing of the feedback depends on the task” (Graesser, 2010, p. 20)..

- “Learning wrong information can be reduced when feedback is immediate” (Graesser, 2010, p. 20).

- “Students benefit more from asking and answering deep questions that elicit explanations (e.g., why, why not, how, what-if) than shallow questions (e.g., who, what, when, where)” (Graesser, 2010, p. 21).

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Use the class outline to note how various activities worked.

References

CAST. (n.d.). Critical Elements of UDL In Instruction | Learning Designed. Learning Designed. Retrieved August 6, 2022, from https://www.learningdesigned.org/resource/critical-elements-udl-instruction.

Gagné, R. M., Wager, W. W., Golas, K., & Keller, J. M. (2005). Principles of Instructional Design (5th ed). Thomson/Wadsworth.

Graesser, A. C. (2010). Scientific Bases of Adult Learning. 2010 APA Education Leadership Conference, Washington DC. https://www.apa.org/ed/governance/elc/2010/media.

Graesser, A. C. (2011). Improving learning. Monitor on Psychology, 42(7). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/07-08/ce-learning.

Graesser, A. C., Halpern, D. F., & Hakel, M. (2007). 25 Learning Principles to Guide Pedagogy and the Design of Learning Environments. Association for Psychological Science Task Force on Life Long Learning at Work and at Home, Washington, DC. https://louisville.edu/ideastoaction/-/files/featured/halpern/25-principles.pdf.

Keller, J. M. (1987). Development and use of the ARCS model of instructional design. Journal of Instructional Development, 10(3), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02905780.

Kennedy, D. (2006). Writing and using learning outcomes: A practical guide. University College Cork. https://cora.ucc.ie/handle/10468/1613.

Mager, R. F. (1997). Preparing Instructional Objectives: A Critical Tool in the Development of Effective Instruction (3 edition). Center for Effective Performance.

Popenici, S., Millar, V., University of Melbourne, & Centre for the Study of Higher Education. (2015). Writing learning outcomes: A practical guide for academics.

Russell, L., & Morrow, M. (1999). The Accelerated Learning Fieldbook: Making the Instructional Process Fast, Flexible, and Fun. Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer.

Svinicki, M. D., & McKeachie, W. J. (2014). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers (Fourteenth edition). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.