B. Learning & Instructional Design Principles

B4. Inclusivity & Diversity in the Class

- Inclusivity & Diversity in the Class

- Defining Diversity

- Two Aspects of Diversity in Teaching – Content & Practices

- Inclusivity for Equal Access

- Universal Design for Learning

- Outside the Classroom

- IDI & Inclusivity for Equal Access

- References

Inclusivity & Diversity in the Class

As an instructor, you will want to create an inclusive environment for all your students to ensure they have equal learning experiences.

A multicultural diverse classroom is a conscious creation advocated and spearheaded by a teacher where … [the teacher] creates a bond and amiable inclusive atmosphere with acceptance and tolerance of diversity. … It can be seen as a classroom where the curriculum has elements of diversity and allow[s] students with exceptionalities to participate in the general education (Sengupta et al., 2019, p.6).

Many institutes are calling for improving student success in HE specifically to create inclusive, equitable opportunities for students (SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee, UNESCO, n.d.; Sengupta et al., 2019; Seymour & Hunter, 2019; TEAM-UP, 2020a). “A key part of this goal is to create inclusive classrooms – both physical classrooms and online classrooms. So, the key question for educators becomes: how can we make classrooms more inclusive?” (Sengupta et al., 2019, p. 4).

Much of this work falls to instructors to provide an inclusive, welcoming environment. Some types of courses such as ESL, business management, English writing, art, education, and music can incorporate diversity into classroom discussions. In others, such as engineering, chemistry, and other ‘hard sciences’, instructors may have difficulty identifying what being more inclusive means.

This chapter defines diversity and talks about why inclusivity matters, what it means, and how you can incorporate inclusivity into your course to provide equal access to learning.

Inclusivity can also be included in the course as part of your goals for transformational learning. For more on this, see Chapter A5.

Student Diversity

Often, HE institutes refer to the ‘traditional college student’ – at one time, the average student was entering HE straight from high school, was living on campus and did not work. Today, the reality is quite different. According to “College Student Demographics | Postsecondary Success,”(2016), almost 50% of students are older, over 33% are part-time, and over 50% work at least part-time. The “College Student Demographics | Postsecondary Success,” (2016) illustrates today’s student in an infographic (Figure). If over 50% of students are employed and over 60% are full-time students, your ‘typical student’ will probably be a ‘non-traditional’ student.

With changes in the American (and world) culture, more students are also willing to indicate their differences in mental health abilities and gender preferences. And, in many universities, instructors are seeing an increase in the number of international students in their classes.

Figure: From “College Student Demographics | Postsecondary Success,” 2016)

Defining Culture, Race And Ethnicity

According to Ormrod et al. (2019, p.109), “the concept of culture encompasses the behaviors and belief systems that characterize a long-standing social group.” Culture, race and ethnicity are often confused. The following comparison is from Lesson Plan – Culture, Race & Ethnicity, n.d.

Culture

Culture is not about superficial group differences or just a way to label a group of people. • It is an abstract concept. • It is diverse, dynamic and ever-changing. • It is the shared system of learned and shared values, beliefs and rules of conduct that make people behave in a certain way. • It is the standard for perceiving, believing, evaluating and acting. • Not everyone knows everything about their own culture.

Race

The term ‘race’ is not appropriate when applied to national, religious, geographic, linguistic or ethnic groups. Race does not relate to mental characteristics such as intelligence, personality or character. • Race is a term applied to people purely because of the way they look. • It is considered by many to be predominantly a social construct. • It is difficult to say a person belongs to a specific race because there are so many variations such as skin colour. • All human groups belong to the same species (Homosapiens).

Ethnicity

Ethnicity is a sense of peoplehood, when people feel close because of sharing a similarity. It is when you share the same things, for example: • physical characteristics such as skin colour or bloodline, • linguistic characteristics such as language or dialect, • behavioural or cultural characteristics such as religion or customs or • environmental characteristics such as living in the same area or sharing the same place of origin.

For many instructors, culture is an unknown – what might different cultures honor/focus on in comparison to others? According to Hofstede (2016), culture can be defined based on several continuums:

- Power Distance Index – “Power Distance is the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions (like the family) accept and expect that power is distributed unequally” (Hofstede, 2016). Some cultures have high respect for authority and rank while others believe power should be distributed.

- Collectivism vs. Individualism – In an individualism society, like many cultures within the USA, individual rights and actions are important. In cultures which focus on collectivism, people focus more on being a part of the whole (Hofstede, 2016). At the individualism end of the scale, people may focus on attaining personal goals. At the collectivism end, people might focus on the good of the group.

- Uncertainty Avoidance Index – ”Uncertainty avoidance deals with a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity” (Hofstede, 2016). In high uncertainty avoidance cultures, risk-taking might be avoided and strict rules might be in place. A lower avoidance culture might respect risk-taking and be more relaxed on rules.

- Femininity vs. Masculinity – Hofstede uses the term ‘tough vs tender’ to differentiate between masculine-focused and feminine-focused cultures. More masculine cultures focus on distinct roles based on gender, with the masculine figure dealing with facts and the feminine dealing with feelings (Hofstede, 2016).

- Short-Term vs. Long-Term Orientation – “In a long-time-oriented culture, the basic notion about the world is that it is in flux, and preparing for the future is always needed. In a short-time-oriented culture, the world is essentially as it was created, so that the past provides a moral compass, and adhering to it is morally good” (Hofstede, 2016). Long-term oriented people would focus more on the future as opposed to the present day.

- Restraint vs. Indulgence – Hofstede differentiates between duty and freedom, here. “In an indulgent culture it is good to be free. Doing what your impulses want you to do, is good. Friends are important and life makes sense. In a restrained culture, the feeling is that life is hard, and duty, not freedom, is the normal state of being” (Hofstede, 2016).

For more details of the 6 dimensions of culture, see GEERT HOFSTEDE (2022).

Important Notes About Culture:

- You can’t tell culture by looking at someone – although an individual may look like they are, for example, Muslim or a South Pacific Islander, that does not mean that they were raised in a culture traditional to one of these groups.

- Culture is always in flux – culture shifts are based on environmental factors, politics, commerce, etc.

- Very few people are exactly defined the same as their primary culture – each person even within a family may be at different points on each continuum.

- Culture is not equal to country of origin – although Hofstede has ‘maps’ showing each country’s continuum point on each scale, countries often have more than one culture. For example, on Hofstede’s ‘map’, New Zealand shows a primary culture high on individualism and low power distance. The Māori culture which focuses on family and whanau (physical, emotional, and spiritual extended family), might show differently. And intercultural families may be defining a new culture.

- Culture has sub-cultures – Few countries have a single culture. Within the Western World culture, we have sub-cultures such as an American culture and within this we have sub-cultures such as a west-coast culture and within this we have San Francisco and within this we have other subcultures.

Defining Diversity

Diversity includes race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation, culture, and religion, but also includes mental and physical ability and immigration status (undocumented aliens, for example). In addition, first-generation college students, students who are parents, and working adults provide more classroom diversity. With some of these groups, such as working adults, you may be able to identify what differences they may bring, some other diverse groups may be more difficult.

And, of course, no person can be defined by just one category of diversity. For example, a single person may be an international ADHD adult working full time with children at home.

However, by being aware that the classroom provides a rich diversity, you can bring in a variety of teaching and learning approaches to not just support the diversity, but to also help each person appreciate and understand better how others are situated. As mentioned above, teaching approaches to increase inclusivity will also help all your learners learn more and better.

Diversity Includes Disability

“People with disabilities are the largest minority group any person can join at any time, and due to accidents and old age eventually do” (Disabled World – Disability News and Information, n.d.). People with disabilities often bring new issues to a classroom, but also bring often very different approaches to problem-solving, group work, etc. while we often think about how we can support disabled students, we do not as often think about the importance of the different perspectives they might bring. Some are obvious: a wheelchaired student in an architecture class, for example. But some are less obvious, such as this report by Manchanda (2019) “I saw a student explain to a peer how his dyslexia made it difficult for him to decode words, but that it also made him a harder, more creative worker.”

International Students

Hudson (2020, p.2) points out that the Western culture perpetrates a myth that individual failure is an individual’s responsibility and that if we treat everyone the same, we are unbiased. Hudson states that we have implicit biases which result in unconscious prejudices. However, in addition to this, treating everyone the same often means treating everyone based on our own cultural preferences, which is implicitly unfair to people of other cultures and backgrounds. Hudson (2020, p.3) continues that many professors are “born into a culture where Whiteness is framed as the norm and respected as the ideal human social identity in the best occupations, media images and history books.”

Many international students have additional difficulties in the classroom. These could be cultural (ex.: some cultures do not expect students to talk during class), language concerns (ex.: English speakers with strong accents may be reluctant to talk), or assumptions about their beliefs (ex.: some students may assume women in burkas will be reluctant to share or have fundamentalist beliefs).

International students may also suffer from culture shock. The following website can help you help your students: International Student.

If you have many international students, create a list of resources for them such as the International Student website. You may also want to review:

- Purdue University Global Learning guide (n.d.). Your institute may have a similar center, providing support to both instructors and students.

- Farnsworth (2018) also points out some of his experiences teaching international students.

Two Aspects of Diversity in Teaching – Content & Practices

Arkoudis et al. (2013, p.222) point out that we need to consider both content and teaching and learning practices. To provide for a diverse student classroom, we need to include diverse content. This includes both using field contributions from minority experts and showing a variety of cultures, peoples, and situations in readings and presentations that balance negative and positive connotations. The TEAM-UP report of The American Institute of Physics (AIP) also found “The connection of physics to activities that improve society or benefit one’s community is especially important to African American students” (TEAM-UP, 2020b, p.36). (For suggestions on inclusive content, see Reid & Maybee, 2021).

Teaching practices need to move beyond the lecture. “Recent evidence indicates that lecturing actively harms underrepresented minority and low-income students” (Freeman & Theobald, 2020). Learning models such as problem-based, case-based, project-based, and inquiry-based learning have been shown to greatly improve achievement of under-represented minority students as well as low-income students (Freeman & Theobald, 2020). Perez (2020) stresses that “fostering a sense of belonging is key to allowing a diverse undergraduate population of STEM majors to flourish.” He continues “Belonging is not merely an abstract concept, but is tied to how resources such as study groups, dialogue with instructors and scholarly reputation are allocated” (Perez, 2020).

Inclusivity for Equal Access

Why Inclusivity is Important for Equal Learning

Hall et al.’s (2011, p.421) research concluded “Interacting with racially diverse peers is positively correlated with social, academic, and non-academic gains.”

Diversity in the classroom has been shown to lead to better student learning. For example, Nawarathne (2019, p.2048) found that including a diversity assignment in organic chemistry “improved students’ knowledge and awareness of versatile carbon bonding, molecular diversity, and social diversity.” Hurtado et al. (as reported by Thiry, 2019, p.400) found that STEM minority students were better able to relate and learn from material that was more relatable to their lives. Students involved in collaborative, diverse learning projects are better able to communicate with and understand others (Loes et al., 2018, p.937).

Many studies have shown that inclusivity in the classroom impacts student acceptance for diversity in other situations. And Loes et al. (2018, p.936) report that “exposure to collaborative learning activities positively influenced students’ openness to diversity, regardless of their individual background characteristics.” “Having contact with diverse individuals, in addition to teaching anti-racist practices, may be important in developing a variety of culturally competent skills” (Jacobsen, 2019, p.390).

As graduates are often hired into positions which include culturally diverse employees, the ability to work inclusively is increasingly important. For example, Padilla-Angulo et al. (2019, p.842) report that graduates in business schools often lack needed entrepreneurial skills, but “interdisciplinary groups have a positive and significant impact on the EI [entrepreneurial intentions] of students by improving their entrepreneurial PBC [perceived behavioural control -self-efficacy], an important predecessor of EI.” Padilla-Angulo et al. (2019) also report that diversity is sought after in business team members and executives. And Gordon et al. (2019, p. 1) report that businesses are expecting employees to be able to work effectively with diverse colleagues.

As we enter an unprecedented academic year, each individual instructor has the power, and responsibility, to ensure belonging is a critical component of course design and pedagogy. To do otherwise not only impedes scientific progress, by excluding the talent of the majority of humanity, but also is an injustice to students who enter our classrooms trusting in the promise of education (Perez, 2020).

STEM Diversity and Inclusion Issues

Nationally, we are not producing as many STEM graduates as are needed for the workforce. STEM majors have a high switch-rate; almost half of students leave their initial STEM major to pursue other majors or leave university. In 1997 and again in 2019, Seymour et al. (2019, p. 1) researched why students leave STEM as a major. As they stated, “The nation can only produce sufficient competent STEM graduates if we can attract and retain more students in these majors…. Our progress is undercut because we still have a revolving door problem: although increasing numbers of students—including those from underrepresented minority groups (URMs) —enter STEM disciplines, losses from these majors remain persistently high” (Seymour et al., 2019, p.2). AIP has also identified this as a major issue and created a special team to identify and make recommendations for retaining students (TEAM-UP, 2020b).

Seymour (2019, p. 438) states while 48% of students entering STEM majors switch to other majors, “switching rates for students of color… are reported in the most recent CIRP and NCES analyses as 42% for African American, 41% for Hispanic students, and 28% for white students.”

Although this is an issue for businesses needing STEM majors, student switching or dropping out face other, more personal issues: “The more serious consequences of STEM switching… however, may be wastage of talent, compromise, or distortion of career aspirations, time and money wasted, debts increased, lost confidence, pride, and a sense of direction—all of which also affect switchers’ families and communities” (Seymour et al., 2019, p.4).

Specifically, among other reasons, Seymour & Hunter (2019) found that students are leaving STEM majors because they do not feel a sense of community or feel a high level of competition, they do not feel prepared for the level of knowledge/learning, and/or could not relate to the material. TEAM-UP (2020b, p. 10) “identified five factors responsible for the success or failure of African American students in physics and astronomy: Belonging, Physics Identity, Academic Support, Personal Support, and Leadership and Structures.”

Certainly, not all issues are within an instructor’s control, but in Talking About Leaving Revisited, Hunter (2019, p.92) reported the following issues of poor teaching, poor curricular design and the negative climate of STEM:

- Competitive, unsupportive STEM culture makes it hard to belong

- Poor quality of STEM teaching

- Negative effects of weed-out classes

- STEM curricular design problems: pace, overload, labs, alignment

- Conceptual difficulties with one or more STEM subject(s)

- Problems related to class size

- Difficulties in seeking and getting appropriate timely help

- Poor teaching, lab or recitation support by TAs

- Language difficulties with foreign instructors or TAs

The TEAM-UP (2020b, p. 15) report from AIP stressed that although faculty can take some actions, department and college action is needed to improve success of African-American students in physics and astronomy. However, among the TEAM-UP recommendations are the following which apply most directly to faculty (TEAM-UP, 2020b):

- With the encouragement and support of their chairs, faculty should learn, practice, and improve skills that foster student belonging in their interactions with African American undergraduates (1a)

- Faculty should feature and discuss a broad range of career options with undergraduates, utilizing resources such as the AIP/SPS Careers Toolbox and the advice of African American alumni (2e)

- Faculty should seek funding for undergraduate students to work in research groups or as Learning Assistants and find other ways to help students advance academically while earning money (4b)

- Faculty and staff should normalize seeking help by discussing stress and self-care with students and referring them to campus resources (4c).

- Faculty should strive to understand that students do not leave behind their identity and experiences when entering the classroom and should recognize the unique promise of each student from a perspective of strengths rather than weaknesses (4d)

- Faculty who teach or advise undergraduates should become aware that counterspaces are important for African American students and should assist students in finding the support they need inside and outside the department (1c)

- Faculty and staff serving as undergraduate advisers should work closely with central advising offices to ensure that students facing academic, financial, and other difficulties can find the support they need (3c)

- Professional societies should lead a coalition, similar to the Societies Consortium on Sexual Harassment in STEMM, to address identity-based harassment beyond sexual harassment. Alternatively, members participating in the Societies Consortium should urge the existing body to broaden its efforts to include all forms of identity-based harassment including microaggressions and acts motivated by racism and bias (1e)

- Professional societies should encourage existing and new groups within their organizations, such as the new APS Forum on Diversity and Inclusion, to examine ways to advance the recommendations of this and similar reports (5e)

Universal Design for Learning

Universal Design for Learning “is a research-based set of principles to guide the design of learning environments that are accessible and effective for all” (CAST, 2018). UDL guidelines are actually applicable to ALL students when considering inclusivity. They also provide guidance on how to proactively introduce inclusivity. “Universal Design for Instruction … requires that faculty anticipate student diversity in the classroom and intentionally incorporate inclusive teaching practices (Scott et al., 2003, p. 10)

The main concepts in UDL are:

- Students who are engaged (actively interested) in the topic learn more deeply

- Students don’t all learn the same way, even if they are actively engaged (some learn better with auditory teaching, others with visual, others with more tactile, others in groups…), so if you can vary the instruction methods you can support more learners

- Students come to class with different levels of study skills, motivation to learn (see ARCS), content information (different schemas), epistemological understanding, etc.

- Learning means more than just acquiring information. Students need to be able to apply that information in appropriate circumstances (and identify when it is appropriate).

UDL Guidelines

CAST provides a series of guiding questions as well as guidelines, both of which can be used as a checklist to help you determine UDL concerns in your course. Details for each point are available on the CAST website (https://udlguidelines.cast.org/more/downloads) in a variety of formats.

How The UDL Guidelines Help

According to Meyer et al. (2016, p.58):

First, they provide a framework for thinking systematically about individual variability as it relates to learning. The Guidelines draw on learning science research to reveal the primary dimensions along which students are likely to vary. They provide scaffolds for remembering who and what to consider in the design of high-performance learning environments. Second, the Guidelines provide concrete suggestions (in the form of “checkpoints”) for how to address systematic variability among students. Those suggestions are the result of a multi-year review of thousands of research articles that identified specific experimentally validated instructional techniques, adaptations, and interventions.

For more information, see:

- Accessibility in Word. (n.d.). [Online Course]. Sacramento State. Retrieved April 12, 2021, from https://csus.instructure.com/courses/54131

- Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2016). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice (1 edition). Cast Incorporated. http://udltheorypractice.cast.org/home?3

Additional UDL Information

Burgstahler, S. (2013). Websites, Publications, and Videos. In Universal Design in Higher Education: Promising Practices (p. 70). DO-IT, University of Washington. https://www.washington.edu/doit/resources/books/universal-design-higher-education-promising-practices

The last few pages of this online book lists websites with specific information such as:

- Universal Design of Web Pages in Class Projects,

- Equal Access: Universal Design of Computer Labs, and

- Universal Design Applications in Biology:

Web pages with further information:

- UDL-Universe: A Comprehensive Faculty Development Guide: UDL Syllabus Rubric

- Universal Design for Learning

- UDL: A Powerful Framework

- Three Principles Of Udl

- CAST

- UDL Checklist (.pdf)

- Poore-Pariseau, C. (2013). Universal Design in Assessments. In Universal Design in Higher Education: Promising Practices (p. 70). DO-IT, University of Washington. www.uw.edu/doit/UDHE-promising-practices/ud_assessments.html

Outside the Classroom

As an instructor you may also want to consider your role in student support outside of the classroom.

- TEAM-UP (2020a, p. 5) suggests that “African American students often face challenges that require assistance from non-faculty experts, and awareness and referral by faculty can improve the students’ utilization of resources.”

- In professional organizations;

- recommend and champion special interest groups to represent the needs and interests of specific groups of marginalized and under-represented students

- pay particular attention during meetings and when reviewing organization material to identity-based harassment and microaggressions (TEAM-UP, 2020b, p. 11).

- At institute and professional organization conferences, art shows, displays, etc., post examples of student work

- Consider starting or joining a mentoring program within your subject-specific context (Arkoudis et al., 2013, p.232)

- The TEAM-UP (2020b, p. 52) report recommends finding funding for undergraduate students to work in research groups or as Learning Assistants.

- If you are an undergraduate adviser, work with central advising offices “to ensure that students facing academic, financial, and other difficulties can find the support they need” (TEAM-UP, 2020b, p. 42).

- Identify counterspaces (“safe spaces”) for undergraduates that provide support for underrepresented groups (TEAM-UP, 2020b, p. 104).

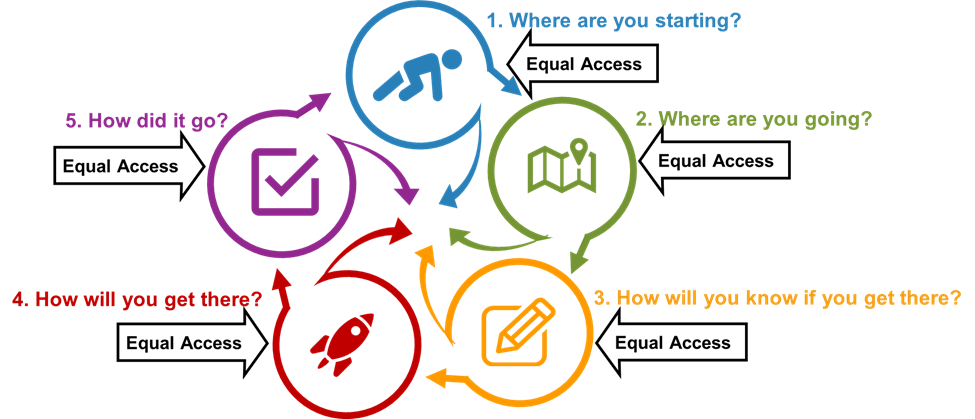

IDI & Inclusivity for Equal Access

The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from transformative learning in the IDI model: (Note additional possible actions in ‘Outside the classroom’ above.)

Step 1. Where are You Starting?

1.2 Identify Student Learning Characteristics

- Especially in first-year courses, do not assume students have the prerequisite prior knowledge (Addy et al., 2020). Consider a first-day pre-test and/or pre-req content review.

Step 2. Where are You Going?

2.2 Finalize Learning Model

- Use strategies that encourage group learning and inquiry-based learning.

Syllabus

- Please note that your organization may have a statement that must be included in your syllabus.

- Develop a graphical version of your syllabus (Quality Learning and Teaching, 2020).

- Give your students your preferred name and pronouns.

- Include a statement about an expectation of respect and consideration for all perspectives and experiences (Booker & Campbell-Whatley, 2018, p.16; Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020). For examples, see Office of Teaching Effectiveness and Innovation, Clemson University, n.d. Arkoudis et al. (2013, p.230) recommend key strategies:

- “Setting clear expectations about peer interaction;

- Respecting and acknowledging diverse perspectives;

- Assisting students to develop rules regarding interaction within their group; Informing students how engaging with diverse learning strategies will assist their learning;

- Providing groupwork resources for students.”

- Include a statement about the value of diversity in groups (Arkoudis et al., 2013, p.233).

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- Review worksheet 3.1a for questionnaires for first-day

- Do not use competition for grades or awards and don’t grade on a curve (Perez, 2020).

Assignment ideas to improve inclusivity

- Assign group homework and assign students to groups.

- “Provide examples and/or illustrations of all major course assignments” (Online Education and Training, California State University system, n.d.).

- Include assignments in which students provide feedback on each other’s work. Explain how this will be used and how it impacts grades.

Flexible assignments

- Provide students with a selection from a series of questions or topics or allow them to propose a topic idea for feedback from the instructor. Include a variety of types of assignments from quizzes, reflections, problem solving assignments, and collaborative work (K. Andrews, personal communication, 2020).

- Identify alternative student options for assignments & testing, such as:

- Alternative presentation methods

- Low-threat assignments & feedback

- Alternative testing methods

- Identify alternative methods of presentation, potentially:

- Group projects

- Videos and texts

- Individual or group presentations

- Written reports (group or individual)

- Provide students with a selection from a series of questions or topics or allow them to propose a topic idea for feedback from the instructor (K. Andrews, personal communication, 2020)

- Use a contract grading system where students can work with you to determine what work they will complete (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020)

- Provide students options for how they complete assignments (K. Andrews, personal communication, 2020)

- Allow students to experiment with different modes of displaying understanding (K. Andrews, personal communication, 2020)

Larger assignments/final projects or papers

- For projects and major assignments, include recommended (or required) steps to complete the task (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020).

- Especially for larger assignments, have check-ins such as a reference list and outline, then first draft, then final.

Group work

Please note that some universities have policies about how instructors group students.

- If you are planning on using group activities/projects, ask students to complete a short questionnaire to identify their skills (Reid & Garson, 2016, p.27).

- Smolcic & Arends (2017, p.60) report that although the students at first found it uncomfortable, matching international and national students in learning groups increased student introspection and awareness of their own and other cultural differences.

- Assign students to groups. “When you work in the real world, you work with whoever you have to work with, and you don’t choose your buddies”. (Holland, 2019, p.313).

- Loes et al. (2018, p.937) suggest groups of no more than 6 students.

- Ask groups to identify at least two methods for group communication, such as in-class discussions and out-of-class discussion boards.

- Ask groups to develop group rules regarding interaction within their group (Arkoudis et al., 2013, p.230).

- Clearly explain how learners will be assessed (including how other group member’s input impacts individual grades).

- Provide clear, well-defined roles and outcomes – include information on typical group roles and on how groups process (ex: Forming, storming norming, performing). Require that students change roles during group projects.

- For longer group work (such as term-long projects) at set times ask the students to change roles.

- Include peer progress reports on larger projects, where students provide feedback to you on how well group members are working together.

- Provide information about implicit bias such as assumed roles that may occur based on group’s cultural and/or gender make-up.

Selecting course materials

- Select readings with diverse images, content, and articles, including diverse practitioners and scholars (Booker & Campbell-Whatley, 2018, p.20).

- Select readings with a balance of deficit- and asset-based images, examples, and depictions of communities (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020).

- Provide examples of multicultural perspectives (Booker & Campbell-Whatley, 2018, p.23; Goldwasser & Hubbard, 2019, p.4, Reid & Maybee, 2021, p.2).

- Consider how you can provide equitable access to materials such as books and articles by using library resources, allowing older editions, and/or using OCR materials. (Addy et al., 2020; Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020).

Feedback

- Reflect on your feedback methods and types to ensure that you are providing constructive, unbiased, and effective feedback (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020; TEAM-UP, 2020b, p. 48). (See ChapterC10 on Feedback).

- “Offer clear and specific feedback on assignments and encourage resubmission of assignments” (Online Education and Training, California State University system, n.d.).

- Consider one-on-one feedback or provide a recording of your comments and feedback.

- Focus on student strengths rather than weaknesses (TEAM-UP, 2020b, p. 48).

- Require peer feedback on assignments (Arkoudis et al., 2013, p.230). Provide students with guidelines or a rubric for providing feedback and explain how the feedback will be used (will it impact grades, will it be used for revisions?…).

- Allow revisions based on feedback.

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.1 Develop & Teach Course

- When asking students to do research, discuss with them the problems with browser algorithms (such as Google) which may provide racist, incorrect and/or slanted results (Noble, 2018).

- Look for “opportunities to bring student reflections into the classroom space for discussion and to develop shared understandings” (Smolcic & Arends, 2017, p.68).

- Use different ways of providing information.

- Use different methods for student interaction

- Paired and small group discussions

- Full-class discussions

- In-class chat sessions during lectures

Possible approaches

- Use online discussion boards and other options for asynchronous group participation (Arkoudis et al., 2013, p.232; Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020).

- To ease asking questions, provide multiple participation methods – synchronous and asynchronous – such as such as whole-class discussions, backchannels, small group discussions, and paired discussions, both in the classroom and online (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020).

- Support collaboration & community (K. Andrews, personal communication, 2020).

- Help students find a study buddy.

- Create a Discussion Board for shared resources.

- Use group activities.

Content considerations for lectures and course readings

- When discussing pioneers in your field, consider international and diverse experts as well as content examples showing a variety of cultures, peoples, and situations (Addy et al., 2020; Reid & Maybee, 2021, p. 2; Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020).

- Discuss a broad range of career options with undergraduates.

- Tell your class about your interactions with diverse colleagues and how this has benefitted you and/or your field.

- Relate the coursework to students’ lives (Thiry, 2019, p.400).

- Review any presentation slides to include diverse images, content, and articles, including diverse practitioners and scholars (Booker & Campbell-Whatley, 2018, p.20).

- Review any presentation slides to ensure you have a balance of deficit- and asset-based images, examples, and depictions of communities (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020).

First Day

- On the first day of classes, ask students to complete a short questionnaire on their background, attributes, expectations, cultural concerns, etc. (Addy et al., 2020).

- Refer to your worksheet 3.1a to identify any questionnaires you want to administer.

- Introduce yourself to your class (Goldwasser & Hubbard, 2019, p.6).

- Tell your students your preferred name and pronouns.

- Begin “the course with explicit statements about the diverse nature of topics discussed in the class and how there was an expectation of respect and consideration for all perspectives and experiences” (Booker & Campbell-Whatley, 2018, p.17).

- Discuss stress and self-care and include syllabus links to student support groups (TEAM-UP, 2020b, p. 5).

- Work with the class to co-develop classroom guidelines (Addy et al., 2020; Arkoudis et al., 2013, p.230).

- Ask students to write note cards (or messages) to you giving their names, their preferred names and preferred pronouns (“he, him”, “she, her”, “they, them”, “zi, zir”, “ze, hir”, etc.). If you do not think you will be able to remember students’ preferred names and/or pronouns, let them know that you will try and ask them to correct you if you mis-speak.

Discussions

- Consider how you will react to microaggressions so you are prepared if needed.

- Discuss implicit bias that the activity may introduce and strategies for removing the bias (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020). For example, are students with accents overtalked or ignored or, just the opposite, given special attention (ex.: People with British accents are sometimes assumed to be more intelligent)?

- Be aware of ‘tokenism’ – that is, watch for signs that a person is being asked to speak for their entire culture, race, religion, disability, etc.

- Start discussions by asking students to pair up to discuss a specific question before asking them to share with the whole class.

- Provide students with blank note cards or an in-class chatroom to ask questions and make comments if they don’t want to talk aloud.

- Pay attention to who is talking. Find non-threatening ways of including others in the discussions. Microaggressions may exclude students from discussions and activities, and stigmate students.

- If some students are dominating the conversation, ask them to hold their thoughts for 2 minutes or ask them to take the opposite view.

- Specifically ask students for different ideas/approaches/examples.

- If you are looking for specific answers (such as math or other facts), consider making it more fun and less threatening by using candy to reward answers – perhaps even incorrect answers.

- After asking a question, wait. Often students will take a while to formulate an answer. Count silently to 15 before talking again.

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Use the class outline to note how various activities worked.

References

Accessibility in Word. (n.d.). [Online Course]. Sacramento State. Retrieved April 12, 2021, from https://csus.instructure.com/courses/54131.

Addy, T. M., Dube, D., & Mitchell, K. A. (2020, August 5). Fostering an Inclusive Classroom. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/08/05/small-steps-instructors-can-take-build-more-inclusive-classrooms-opinion.

Arkoudis, S., Watty, K., Baik, C., Yu, X., Borland, H., Chang, S., Lang, I., Lang, J., & Pearce, A. (2013). Finding common ground: Enhancing interaction between domestic and international students in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.719156.

Bass, G., & Lawrence-Riddell, M. (2020, January 6). UDL: A Powerful Framework. Faculty Focus | Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/course-design-ideas/universal-design-for-learning/.

Booker, K. C., & Campbell-Whatley, G. D. (2018). How Faculty Create Learning Environments for Diversity and Inclusion. InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching, 13, 14–27.

Burgstahler, S. (2013). Websites, Publications, and Videos. In Universal Design in Higher Education: Promising Practices (p. 70). DO-IT, University of Washington. www. uw.edu/doit/UDHE-promising-practices/resources.html.

CAST. (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org/.

Center for Teaching Excellence. (n.d.). Global Learning—Center for Instructional Excellence—Purdue University. Purdue University Center for Teaching Excellence. Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://www.purdue.edu/cie/globallearning/.

College Student Demographics | Postsecondary Success. (2016, October 3). Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation – Postsecondary Success. https://postsecondary.gatesfoundation.org/what-were-learning/todays-college-students/.

Disabled World—Disability News and Information. (n.d.). Disabled World. Retrieved September 23, 2020, from https://www.disabled-world.com/.

Farnsworth, B. (2018, July 2). Enhancing the Quality of the International Student Experience. Higher Education Today. https://www.higheredtoday.org/2018/07/02/enhancing-quality-international-student-experience/.

Freeman, S., & Theobald, E. (2020, September 2). Is Lecturing Racist? Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/09/02/lecturing-disadvantages-underrepresented-minority-and-low-income-students-opinion.

Gordon, S. R., Yough, M., Finney, E. A., Haken, A., & Mathew, S. (2019). Learning about Diversity Issues: Examining the Relationship between University Initiatives and Faculty Practices in Preparing Global-Ready Students. Educational Considerations, 45(1). https://eric.ed.gov/?q=Diversity+in+the+classroom+better+student+learning&ff1=dtySince_2016&ff2=eduHigher+Education&pg=2&id=EJ1219107.

Hall, W. D., Cabrera, A. F., & Milem, J. F. (2011). A Tale of Two Groups: Differences Between Minority Students and Non-Minority Students in their Predispositions to and Engagement with Diverse Peers at a Predominantly White Institution. Research in Higher Education, 52(4), 420–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9201-4.

Hofstede, G. (2016, February 1). The 6D model of national culture. Geert Hofstede. https://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/.

Holland, D. G. (2019). The Struggle to Belong and Thrive. In E. Seymour & A.-B. Hunter (Eds.), Talking about Leaving Revisited (pp. 277–327). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2_9.

Hudson, N. J. (2020). An In-Depth Look at a Comprehensive Diversity Training Program for Faculty. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 14(1). https://eric.ed.gov/?q=diversity+in+classroom&ff1=dtySince_2016&ff2=subTeaching+Methods&ff3=eduHigher+Education&pg=2&id=EJ1256240.

Hunter, A.-B. (2019). Why Undergraduates Leave STEM Majors: Changes Over the Last Two Decades. In E. Seymour & A.-B. Hunter (Eds.), Talking about Leaving Revisited (pp. 87–114). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2_3.

Jacobsen, J. (2019). Diversity and Difference in the Online Environment. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 39(4–5), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2019.1654589.

Lesson plan—Culture, race & ethnicity. (n.d.). LESSON PLAN – CULTURE, RACE & ETHNICITY. Retrieved July 31, 2022, from https://www.harmony.gov.au/get-involved/schools/lesson-plans/lesson-plan-culture-race-ethnicity.

Loes, C. N., Culver, K. C., & Trolian, T. L. (2018). How Collaborative Learning Enhances Students’ Openness to Diversity. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(6), 935–960. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2018.1442638.

Manchanda, S. (2019, August 12). I started talking about disability in my classroom. It changed both me and my students. Chalkbeat. https://www.chalkbeat.org/2019/8/12/21108612/i-started-talking-about-disability-in-my-classroom-it-changed-both-me-and-my-students.

Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice (1 edition). Cast Incorporated. http://udltheorypractice.cast.org/home?3.

Nawarathne, I. N. (2019). Introducing Diversity through an Organic Approach. Journal of Chemical Education, 96(9), 2042–2049. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.8b00646.

Office of Teaching Effectiveness and Innovation, Clemson University. (n.d.). Diversity & Inclusion Syllabus Statements. Office of Teaching Effectiveness and Innovation, Clemson University. Retrieved September 30, 2020, from https://www.clemson.edu/otei/resources/review-of-teaching.html.

Padilla-Angulo, L., Díaz-Pichardo, R., Sánchez-Medina, P., & Ramboarison-Lalao, L. (2019). Classroom interdisciplinary diversity and entrepreneurial intentions. Education + Training, 61(7/8), 832–849. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2018-0136.

Perez, K. M. (2020, September 8). Fostering a Sense of Belonging in STEM. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/09/08/encouraging-sense-belonging-among-underrepresented-students-key-their-success-stem.

Poore-Pariseau, C. (2013). Universal Design in Assessments. In Universal Design in Higher Education: Promising Practices (p. 70). DO-IT, University of Washington. www.uw.edu/doit/UDHE-promising-practices/ud_assessments.html.

Quality Learning and Teaching. (2020, January 24). LibGuides: UDL-Universe: A Comprehensive Faculty Development Guide: UDL Syllabus Rubric. UDL-Universe: A Comprehensive Faculty Development Guide: Home. https://enact.sonoma.edu/c.php?g=789377&p=5650618.

Quality Learning and Teaching. (2020, January 24). LibGuides: UDL-Universe: A Comprehensive Faculty Development Guide: UDL Syllabus Rubric. UDL-Universe: A Comprehensive Faculty Development Guide: Home. https://enact.sonoma.edu/c.php?g=789377&p=5650618.

Reid, P., & Maybee, C. (2021). Textbooks and Course Materials: A Holistic 5-Step Selection Process. College Teaching, 0(0), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2021.1987182.

Scott, S., Mcguire, J., & Shaw, S. (2003). Universal Design for Instruction: A New Paradigm for Adult Instruction in Postsecondary Education. Remedial and Special Education – REM SPEC EDUC, 24, 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325030240060801.

SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committee, UNESCO. (n.d.). Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) | Education within the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [UNESCO]. SDG-Education 2030 Steering Committees. Retrieved September 20, 2020, from https://sdg4education2030.org/the-goal.

Sengupta, E., Blessinger, P., Hoffman, J., & Makhanya, M. (2019). Introduction to strategies for fostering inclusive classrooms in higher education. In Strategies for Fostering Inclusive Classrooms in Higher Education: International Perspectives on Equity and Inclusion. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/S2055-364120190000016005/full/html.

Seymour, E. (2019). Then and Now: Summary and Implications. In E. Seymour & A.-B. Hunter (Eds.), Talking about Leaving Revisited (pp. 437–473). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2_13.

Seymour, E., & Hunter, A.-B. (Eds.). (2019). Talking about Leaving Revisited: Persistence, Relocation, and Loss in Undergraduate STEM Education. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2.

Seymour, E., Hunter, A.-B., & Weston, T. J. (2019). Why We Are Still Talking About Leaving. In E. Seymour & A.-B. Hunter (Eds.), Talking about Leaving Revisited (pp. 1–53). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2_1.

Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning. (2020). Effective Teaching Is Anti-Racist Teaching. Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, Brown University, 1812. https://www.brown.edu/sheridan/teaching-learning-resources/inclusive-teaching/effective-teaching-anti-racist-teaching.

Smolcic, E., & Arends, J. (2017). Building Teacher Interculturality: Student Partnerships in University Classrooms. Teacher Education Quarterly, 44(4), 51–73.

TEAM-UP. (2020a). The Time Is Now: Recommendations (No. 978-1-7343469-0–9; Team-Up, p. 186). American Institute of Physics. https://www.aip.org/diversity-initiatives/team-up-task-force.

TEAM-UP. (2020b). The Time Is Now: Systemic Changes to Increase African Americans with Bachelor’s Degrees in Physics and Astronomy (No. 978-1-7343469-0–9; Team-Up, p. 186). American Institute of Physics. https://www.aip.org/diversity-initiatives/team-up-task-force.

Thiry, H. (2019). What Enables Persistence? In E. Seymour & A.-B. Hunter (Eds.), Talking about Leaving Revisited (pp. 399–436). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2_12.

Universal Design For Learning. (n.d.). The Teaching Commons, Georgetown University. Retrieved July 12, 2020, from https://commons.georgetown.edu/teaching/design/universal-design/.