C. Teaching Practices

C10. Feedback on Student Assignments & Assessments

Feedback on Student Assignments & Assessments

(For information on selecting, designing, and scheduling assessments, see Chapter C7. For information about receiving feedback from students, see Chapter C12.)

“Feedback is one of the most powerful influences on learning and achievement” (Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p. 81). To provide students with feedback, you will need to provide formative assessments which monitor how the student is doing and provide both the students and instructor guidance on how to improve (Eberly Center, n.d.).

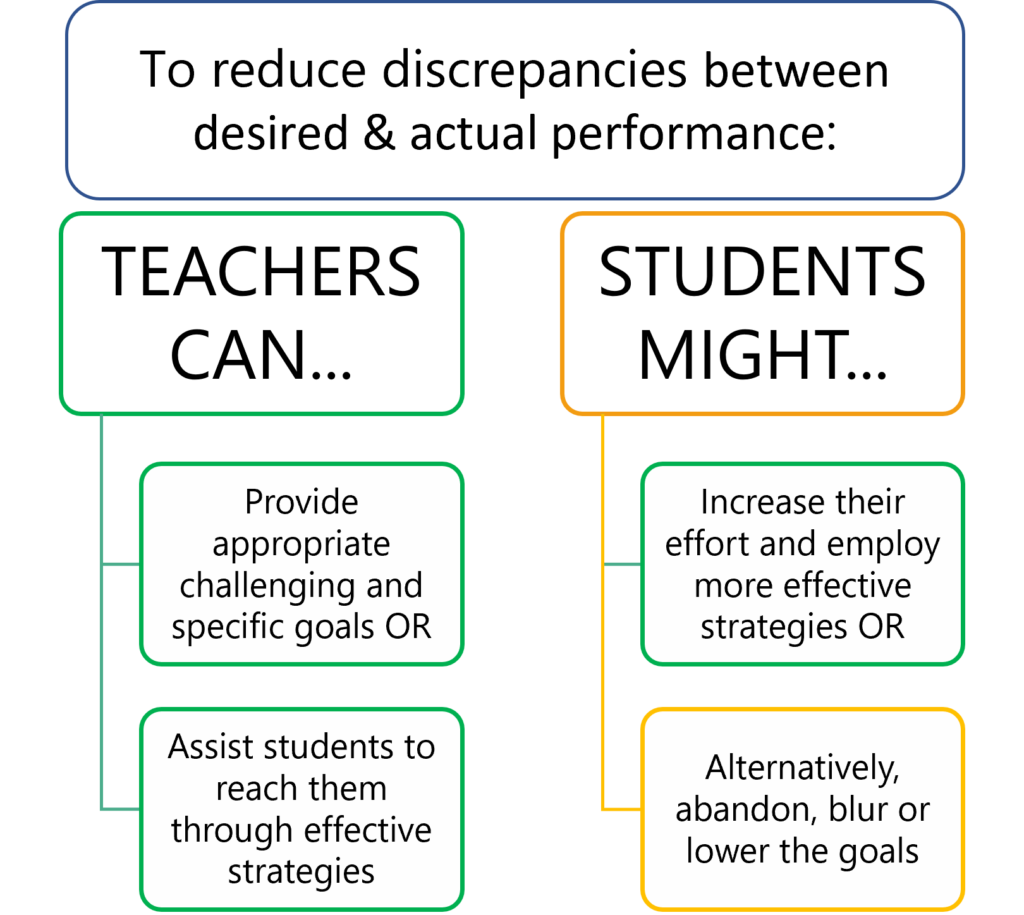

Feedback helps students “reduce discrepancies between current understandings/performance and a desired goal” (Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p.86). To do this, feedback needs to be carefully formatted and provided, providing information on current performance compared to a clear goal. However, the feedback should also provide guidance on how the student can improve. By combining both feedback on the current work and information for improvement, the feedback becomes instruction.

Wiggins (2012) defines the essentials of good feedback as:

- Goal-Referenced

- Tangible and Transparent

- Actionable

- User-Friendly

- Timely

- Ongoing

- Consistent

Why Is Formative Feedback Important?

When I was taking my masters classes, I had the same instructor for several courses. On every essay I received “Nice job. I enjoyed reading this. A-“. The guy who sat next to me always received “Nice job. I enjoyed reading this. A+“. Neither of us received any other comments. I had no idea how to improve and basically gave up trying to get beyond the A-.

Hattie & Timperley (2007, p. 82) explain that feedback can be instructional if the feedback is combined with correction. However, if the feedback is not clear, the student may not realize what they did wrong and what they need to learn (Hattie, 2018) (Figure 1). Without feedback, students try to determine how to act on future assessments (Hattie et al., 2015, p. 175). The students can take a positive or negative approach to this.

Instructor feedback can help students take positive approaches to removing differences between desired and actual performance. By providing effective feedback – providing guidance on what was wrong, what can be improved, how it can be improved, and how this shows improvement from the last effort – instructors can help students improve. Without appropriate feedback, the students are often at a loss on how to improve. In fact, repeated practice without feedback can actually reinforce incorrect learning. Incorrect work which is marked incorrect but without good feedback can actually do more harm than good. (Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p. 87) (2007, p. 87) defined the options as improving or giving up (Figure 1).

Figure 1: How to Reduce Discrepancies between Desired & Actual Performance (adapted from Hattie & Timperley, 2007, p. 87)

SOLO (Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome)

The Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome (SOLO) taxonomy is primarily used when evaluating student work. The SOLO taxonomy classifies understanding into five (5) levels (From FutureLearn, n.d.):

- Prestructural: at this level the learner is missing the point.

- Unistructural: a response based on a single point.

- Multistructural: a response with multiple unrelated points.

- Relational: points presented in a logically related answer.

- Extended abstract: demonstrating an abstract and deep understanding through unexpected extension.

According to Biggs (n.d.):

As learning progresses it becomes more complex. SOLO… is a means of classifying learning outcomes in terms of their complexity, enabling us to assess students’ work in terms of its quality not of how many bits of this and of that they have got right. At first we pick up only one or few aspects of the task (unistructural), then several aspects but they are unrelated (multistructural), then we learn how to integrate them into a whole (relational), and finally, we are able to generalised that whole to as yet untaught applications (extended abstract).

Student use of the taxonomy can help them understand their own level of understanding (Taken from Frame (n.d.):

Students can categorise their own understanding in this taxonomy, or the difficulty of a lesson or question. They can see what they need to do to understand the topic at the next level. And they can appreciate why they need to learn apparently disparate facts – only when they’ve done that can they link them all together in the next lesson.

Using SOLO taxonomy involves learners in their own differentiation and makes the process behind learning explicit. It highlights the difference between surface and deep understanding, helping students understand where they are on that spectrum, and what they need to do to progress.

Students become aware of the reasons for everything they do and realize improvements are due to their own strategies rather than luck or fixed ability.

SOLO Taxonomy Table of Verbs

- For SOLO verbs and examples, see Table 1 (opens .pdf in new tab).

- For an example of a SOLO grading rubric, see FULT_ePortfolio_marking_rubric (n.d.).

- For more on SOLO, see the book: Biggs, J., & Collis, K. F. (1982). Evaluating the quality of learning: The SOLO taxonomy (structure of the observed learning outcome). Academic Press.

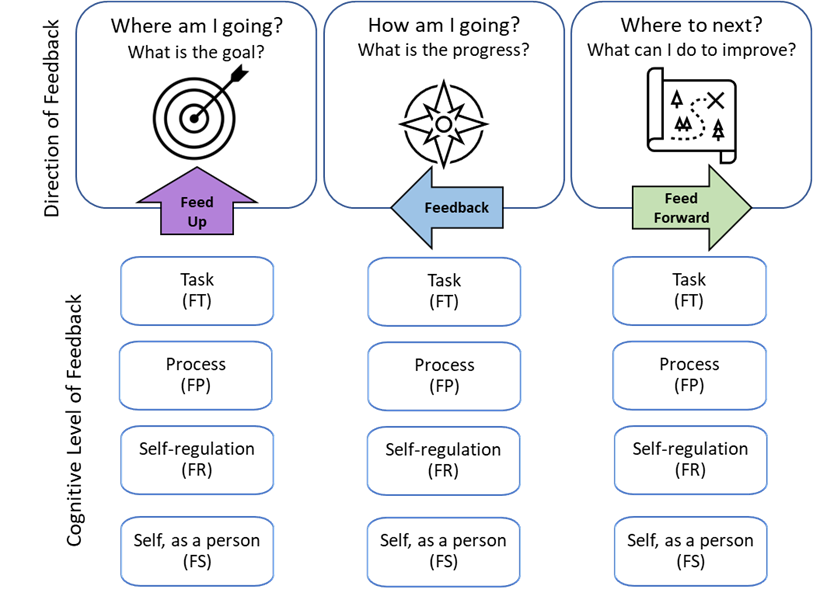

Types of Feedback – Direction

Hattie and Timperley (2007) described feedback as separated into three directions (Figure 2) – Feed up, Feedback, and Feed forward and each direction can have four levels of feedback. Wisniewski et al. (2020, p.2) explain:

Feedback can have different perspectives: “feed-up” (comparison of the actual status with a target status, providing information to students and teachers about the learning goals to be accomplished), “feed-back” (comparison of the actual status with a previous status, providing information to students and teachers about what they have accomplished relative to some expected standard or prior performance), and “feed-forward” (explanation of the target status based on the actual status, providing information to students and teachers that leads to an adaption of learning in the form of enhanced challenges, more self-regulation over the learning process, greater fluency and automaticity, more strategies and processes to work on the tasks, deeper understanding, and more information about what is and what is not understood).

Each of the three directions of feedback can be given on four levels (Figure 2): Feedback about:

- task performance (FT)

- the process (FP)

- self-regulation (FR)

- self, as a person (FS)

Figure 2: Direction & Level of Feedback Based on Hattie & Timperley (2007)

(View image as Google sheet in new tab)

Wisniewski et al. (2020, p.2) explain:

Feedback can be differentiated according to its level of cognitive complexity: It can refer to a task, a process, one’s self-regulation, or one’s self. Task level feedback means that someone receives feedback about the content, facts, or surface information (How well have the tasks been completed and understood? Is the result of a task correct or incorrect?). Feedback at the level of process means that a person receives feedback on the strategies of his or her performance. Feedback at this level is aimed at the processing of information that is necessary to understand or complete a certain task (What needs to be done to understand and master the tasks?). Feedback at the level of self-regulation means that someone receives feedback about the individual’s regulation of the strategies they are using to their performance. In contrast to process level feedback, feedback on this level does not provide information on choosing or developing strategies but to monitor the use of strategies in the learning process. It aims at a greater skill in self-evaluation or confidence to engage further on a task (What can be done to manage, guide and monitor your way of action?). The self level focuses on the personal characteristics of the feedback recipient (often praise about the person)[emphasis added].

The combinations of direction and level of the feedback must be considered to construct the most effective feedback. For more information on Hattie’s feedback model, see the 2015 book Visible Learning into Action (Hattie et al., 2015) and The applicability of Visible Learning to higher education. (Hattie, 2015).

Examples of Feedback

- Description of each feedback type with examples from Missouri EduSAIL (n.d.)- Table (.pdf opens in another tab)

- Student self-assessment feedback from Harris et al. (2015, p.8) – Table (.pdf opens in another tab)

- Instructor feedback form designed to provide faster yet more detailed feedback from S. Taylor (2013) – Table (.pdf opens in another tab)

- For an example of a peer and self-feedback form designed to help students provide clear and specific feedback see Table by S. Taylor (2013) (.pdf opens in another tab)

Using Rubrics for Feedback

“Students rarely have an accurate knowledge of their cognition so their ability to calibrate their comprehension, learning, and memory should not be trusted” (Graesser, 2010, p. 22). Feedback can help students realize what they don’t know, what they did wrong, and what they need to do to improve.

Rubrics can provide you and students with a clear description of what is expected on assignments. They tell students what you and they should focus on and to what standard or level they should be able to perform.

Rubrics can also be used for easier grading and feedback. A rubric can focus on “evidence of critical reflection in terms of content, process and premise. Content reflection consists of curricular mapping from student and faculty perspectives; process reflection focuses on best practices, literature-based indicators and self-efficacy measures; premise reflection would consider both content and process reflection to develop recommendations” (Culatta, n.d.).

Examples of rubrics are available at the AAC&U site: Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE), n.d.

When creating assignments, consider asking the students to include a self-reflective copy of the rubric. If they have been ignoring the rubric, this is a good method to have them focus more on expectations. Rubrics can also be provided for peer assessments.

For each assessment/assignment, develop a clear definition of how you will assign points/grades.

Rubric Support:

- How to build a rubric – Indiana University Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning webpage Rubric Creation and Use (Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning, n.d.).

- Examples of rubrics and formatting – AACU site Sample Rubrics – http://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics.

List of Automated Rubric Creation Tools:

- Epperson, A. (2016, September 28). Rubric Maker—Where to Create Free Rubrics Online. PBIS Rewards. https://www.pbisrewards.com/blog/free-online-rubric-maker/.

- College of Technology, Instructional Design Office. (n.d.). Rubric Tool. University of Houston. Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.uh.edu/tech/instructional-design/learn-with-cot-id/best-practices/blackboard-rubric-tool/index.

- Rubric Resources – Albright College. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.albright.edu/academic/faculty-resources/teaching-and-learning-resources/albright-faculty-toolkit/rubric-resources/.

IDI & Feedback to Students

The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from Feedback to Students in the IDI model:

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- Create rubric forms (from Killian, 2018) to:

- Affirm what they did well.

- Correct and direct.

- Point out the process.

- Coach students to critique their own efforts.

- Review the rubric against the SOLO taxonomy to ensure you are targeting feedback to the appropriate level.

- Identify common student errors and develop appropriate feedback for each, using Hattie’s model.

- Include objectives for each assessment and how they link to learning outcomes.

- Develop peer and self-feedback rubrics and forms.

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.2 Assess Students

- Use the pre-developed feedback and the feedback form (Worksheet 4.2 – Optional – Assignment Feedback Form) to provide appropriate feedback.

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Use the class outline to note how well the feedback helped students.

References

Biggs, J. (n.d.). SOLO Taxonomy. John Biggs. Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.johnbiggs.com.au/academic/solo-taxonomy/.

Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Rubric Creation and Use. Indiana University Bloomington. Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://citl.indiana.edu/teaching-resources/assessing-student-learning/rubric-creation-use/index.html.

College of Technology, Instructional Design Office. (n.d.). Rubric Tool. University of Houston. Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.uh.edu/tech/instructional-design/learn-with-cot-id/best-practices/blackboard-rubric-tool/index.

Culatta, R. (n.d.). Transformative Learning (Jack Mezirow). InstructionalDesign.Org. Retrieved June 4, 2022, from https://www.instructionaldesign.org/theories/transformative-learning/.

Eberly Center. (n.d.). Formative vs Summative Assessment. Elberly Center – Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/assessment/basics/formative-summative.html.

Epperson, A. (2016, September 28). Rubric Maker—Where to Create Free Rubrics Online. PBIS Rewards. https://www.pbisrewards.com/blog/free-online-rubric-maker/.

Frame, R. (n.d.). What is SOLO taxonomy? RSC Education. Retrieved July 6, 2020, from https://edu.rsc.org/ideas/what-is-solo-taxonomy/3008902.article.

FULT ePortfolio marking rubric. (n.d.). From Introduction to Learning and Teaching in Higher Education, UNSW Sydney. https://ugc.futurelearn.com/uploads/files/ea/57/ea57852a-d368-433f-9bfc-deeed51028e0/FULT_ePortfolio_marking_rubric_FINAL.pdf.

FutureLearn. (n.d.). Introduction to the SOLO taxonomy. FutureLearn. Retrieved July 4, 2020, from https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/learning-teaching-university/0/steps/26410.

Graesser, A. C. (2010). Scientific Bases of Adult Learning. 2010 APA Education Leadership Conference, Washington DC. https://www.apa.org/ed/governance/elc/2010/media.

Harris, L. R., Brown, G. T. L., & Harnett, J. A. (2014). Analysis of New Zealand primary and secondary student peer- and self-assessment comments: Applying Hattie and Timperley’s feedback model. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(2), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.976541.

Hattie, J. (2015). The applicability of Visible Learning to higher education. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 1(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000021.

Hattie, J. (2018, June 20). Getting Feedback Right: A Q&A With John Hattie – Education Week (S. D. Sparks, Interviewer) [Education Week]. https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2018/06/20/getting-feedback-right-a-qa-with-john.html.

Hattie, J., Masters, D., & Birch, K. (2015). Visible learning into action. Routledge.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487.

Killian, S. (2018, December 26). Feedback: The First Secret John Hattie Revealed. EVIDENCE-BASED TEACHING. https://www.cnyric.org/tfiles/folder1306/Feedback_%20The%20First%20Secret%20John%20Hattie%20Revealed%202.15.19.pdf.

MoEdu-SAIL. (n.d.). Strategy 3: Levels of Feedback. Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education: Northern Arizona University, Institute for Human Development. Retrieved November 11, 2022, from https://www.moedu-sail.org/topic/strategy-3-levels-feedback/.

Rubric Resources – Albright College. (n.d.). Retrieved November 3, 2022, from https://www.albright.edu/academic/faculty-resources/teaching-and-learning-resources/albright-faculty-toolkit/rubric-resources/.

Taylor, S. (2013, November 3). Making Feedback Visible: Four Levels Experiment. Wayfinder Learning Lab. https://sjtylr.net/2013/11/03/making-feedback-visible-four-levels/.

Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education (VALUE). (n.d.). AAC&U. Retrieved June 26, 2022, from https://www.aacu.org/initiatives/value.

Wiggins, G. (2012, September). Seven Keys to Effective Feedback—Educational Leadership. Educational Leadership, 70(1), 10–16.

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The Power of Feedback Revisited: A Meta-Analysis of Educational Feedback Research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087.