C. Teaching Practices

C2. Learning Goals

- Learning Goals, Outcomes, & Objectives

- The Flow from Outcomes to Objectives

- Course Learning Outcomes

- Learning Outcomes vs Learning Objectives

- Writing Learning Outcomes

- Writing Objectives

- Sequencing Outcomes & Objectives

- IDI & Course Outcomes & Objectives

- References

Learning Goals, Outcomes, & Objectives

A critical part of good course design is the development of the learning outcomes and objectives. These provide guidance to you on how to develop all other parts of your course.

They also provide students with guidance on where they should focus their learning. Berrett (2012) notes:

Whatever method a faculty member attempts…he or she should start by defining the underlying concepts to be taught and the learning outcomes that will be demonstrated. And it is not enough… to simply declare that the learning outcome is to cover the first four chapters of a textbook. …It's a whole different paradigm of teaching… likening the professor's role to that of a cognitive coach. A good coach figures out what makes a great athlete and what practice helps you achieve that. They motivate the learner to put out intense effort, and they provide expert feedback that's very timely.

Fowler (2016) explains part of the need for courses outcomes:

while it is quite likely that the instructor is very good in his or her field, unless there is some general standard by which all sections of a course are explicitly measured, there is no way to assess whether students across sections are succeeding and no way of systematically determining where, if the student learning environment is failing the student, such failures are occurring. Is it the student, instructor or learning resource that needs to be reviewed?... Simply put, well-defined student learning outcomes combined with valid assessments enable an institution to ensure that regardless of who is teaching the course, all students who succeed have demonstrated the stated performances.

Well-written course outcomes help you as well as: your students, people teaching pre-req and post-reqs, your program committee, and, especially at accreditation time, your institution.

The Flow from Outcomes to Objectives

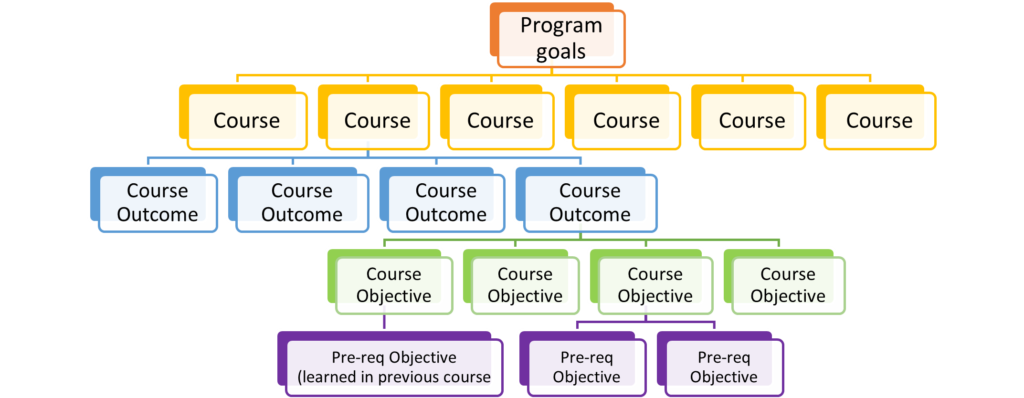

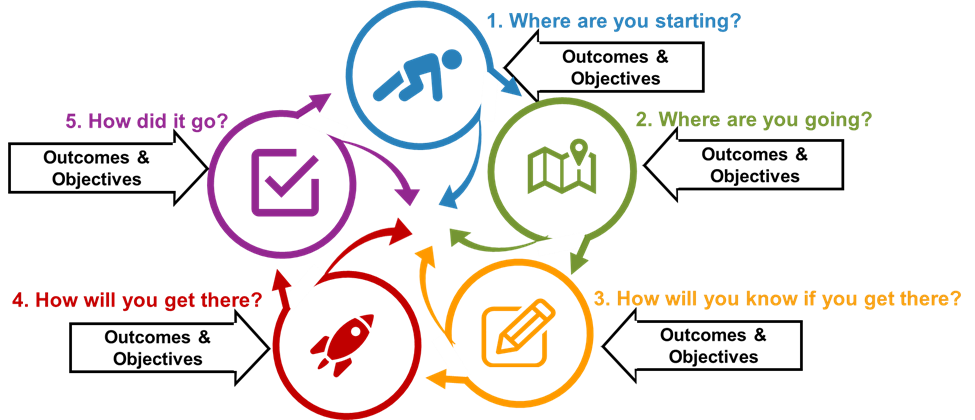

In this workbook, ‘goals’ refers to the large program goals, outcomes are specific goals for the course, and objectives are how you will meet the outcomes (See Figure 1).

- The successful completion of all objectives should result in the successful completion of the course outcomes.

- The successful completion of course outcomes from all courses in the program should result in the successful completion of the program.

Course Learning Outcomes

Figure 1: Relation of Goals, Outcomes, & Objectives

Considerations when developing course outcomes:

- What are your institute’s requirements?

- What are your program’s requirements?

- What do you want your students to learn (not just what material, but also consider transformative learning, threshold concepts, metacognitive growth, etc.)? This may be influenced by your philosophy of education, your specific field of study, your students’ majors, the level of the course, and other factors.

Program goals

Each program has specific goals of what students should be able to do as a result of completing the program. Program goals are typically also defined at a course level and are approved by the department, university, the accrediting body, and possibly several other entities such as the state.

Program goals lead to the identification of courses. Each course has specific outcomes which, when combined with all the other courses, support the program goals. Together, the courses in the program are responsible for meeting all the goals. Some program goals may meet institute goals (such as foundational outcomes.

Because your course is one in a series, future courses may require that students learn specific skills, knowledge and/or attitudes (SKAs) in your course. Therefore, you should check with these course instructors to determine what outcomes and objectives you need to include in your course.

While the program committee will have approved the program goals, the course outcomes are frequently redefined by each instructor (this may result in the same course, taught by different instructors, having different outcomes and focuses). To ensure that the program goals are still met, instructors must understand how each course supports the program(s).

Some courses are required for multiple majors. For example, The Ohio Stater University course Teaching Reading Across the Curriculum is taken by both Agriscience Education majors and Career and Technical Education majors. For these courses, instructors need to be aware of how the course fits into each major to ensure that the goals of each are met.

Course outcomes are large, so are broken down into manageable parts called course objectives. Some course objectives may have pre-requisite objectives which might be covered in a previous course or in this course (which will help you identify sequencing).

In addition, if your course is not a first-year course, your students will enter with SKAs. By reading the course descriptions and outcomes for previous courses, you can determine a starting point or level for your course.

Contact your program coordinator and/or department administrator for help finding program documentation.

Suggestions:

- Remember your course may be a part of multiple programs.

- If you have not discussed your outcomes with the instructors teaching the pre- or post-requisite courses recently, you may find it helpful to ensure that you agree about the expectations of your class.

- Check if your program committee has developed threshold concept outcomes for the program and, if so, which may apply to your course.

Institute Requirements for Course Outcomes

(Although the term Foundational is used in this workbook, these requirements might be listed in your institute as Foundational, VALUE, General, Common Requirements, or may have a different title.)

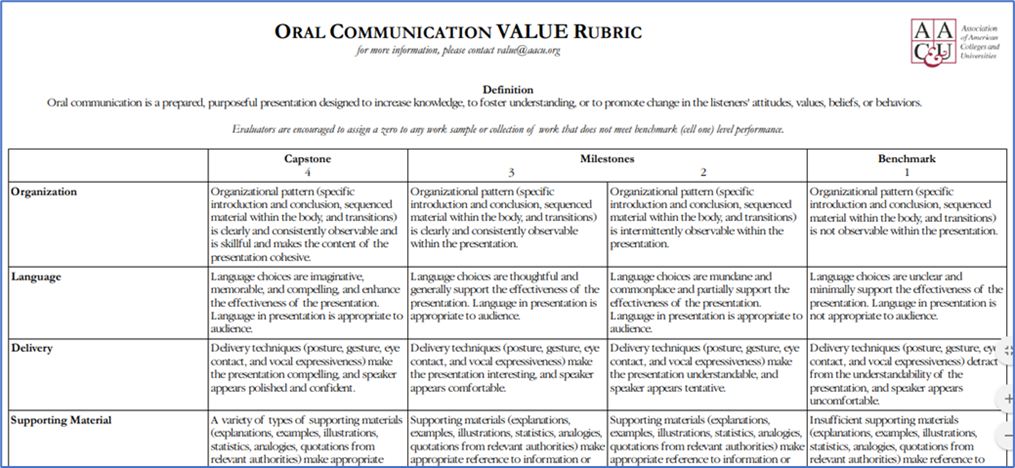

Many institutes also require that their students achieve learning outcomes not specific to their discipline. For example, a common requirement is that students learn some basic oral communication skills. Many courses may have some of these requirements. Although the requirements may not be listed in the course catalog, as an instructor, you may be required to include the requirements in your course. The following examples

Examples of Foundational Learning Outcomes

Figure 2: Oral Communication VALUE Extract

Extracted from the AAUC Values Rubrics site (Rhodes, 2010), the definition of Oral Communications is “Oral communication is a prepared, purposeful presentation designed to increase knowledge, to foster understanding, or to promote change in the listeners’ attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors.” (See Figure 2 for a sample of the rubric.) (Access as .pdf from AAUC website)

Table 1: Purdue University foundational learning outcomes

From Purdue University (Expected Outcomes – Office of the Provost – Purdue University, n.d.), the foundational learning outcomes for Communications include: (Skip)

3. ORAL COMMUNICATION Requirement: One course -- activity of conveying meaningful information verbally; communication by word of mouth typically relies on words, visual aids and non-verbal elements to support the conveyance of the meaning. Oral communication is designed to increase knowledge, foster understanding, or to promote change in the listener’s attitudes, values, beliefs, or behaviors. Key Skills: • Uses appropriate organizational patterns (introduction, conclusion, sequenced material, transitions) that is clearly and consistently observable when making presentations • Uses language that is thoughtful and generally supports the effectiveness of the presentation (and is appropriate to the audience). • Uses appropriate delivery techniques when making a presentation (posture, gesture, eye contact, vocal expression) • Effectively uses supporting materials in presentations (explanations, examples, illustrations, statistics, analogies, quotations) • Clearly communicates a central message with the supporting materials

Table 2: Program: Communication, BA – Purdue University

COM 11400 - Fundamentals Of Speech Communication (satisfies Oral Communication for core) (Skip) COM 11400 - Fundamentals Of Speech Communication Credit Hours: 3.00. A study of communication theories as applied to speech; practical communicative experiences ranging from interpersonal communication and small group process through problem identification and solution in discussion to informative and persuasive speaking in standard speaker-audience situations. Typically offered Fall Spring Summer. NOTE: Concurrent registration is not permitted for ENGL 10600 and COM 11400. CTL:ICM 1103 Fundamentals Of Public Speaking Credits: 3.00

Table 3: Assessment and Reaffirmation of Foundational Oral Communication Outcome

Sample extracted from the Purdue University examples of courses meeting foundational outcomes (Assessment and Reaffirmation of Foundational Oral Communication Outcome, n.d.): (Skip)

Assessment and Reaffirmation of Foundational Oral Communication Outcome Report Template Course name and section number: COM 114 Learning outcomes for oral communication: • Students will be able to use appropriate organizational patterns (introduction, conclusion, sequenced material, transitions) during presentations. • Students will be able to use language that is thoughtful and generally supports the effectiveness of the presentation (and is appropriate to the audience). • Students will be able to use appropriate delivery techniques when making a presentation (posture, gesture, eye contact, vocal expression). • Students will be able to effectively use supporting materials in presentations (explanations, examples, illustrations, statistics, analogies, quotations). • Students will be able to clearly communicate a central message with the supporting materials. Provide a short description of the work that students performed to meet the oral communication outcome: Students gave a 3-5 minute presentation persuading their classmates to support or join a charity or nonprofit organization, or to attend a specific event put on by such an organization. Specific criteria for the presentation included; use an appropriate organizational pattern, use at least four sources, use an extemporaneous delivery style, develop a thesis that previews your main points, and develop two main points with strong support.

Your Goals

In addition to program and institutional goals, you may have other goals, influenced by your philosophy of education, your specific field of study, the level of the course, and other factors.

Some course outcomes will be obvious based on the course description. Others may be identified when you review the course pre- and post-requisites. You also may identify outcomes when you think through your responsibilities as an educator; for example, you may identify learning outcomes based on Fink’s significant learning taxonomy, how you see inclusivity fitting into your course, or your epistemology.

To help you identify your goals, you may want to take the Teaching Goals Inventory, available free online in these locations:

- Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (n.d.). Teaching Goals Inventory. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://tgi.its.uiowa.edu/ (provides automated reports.

- Cross, K. P., & Angelo, T. A. (1988). Classroom Assessment Techniques. A Handbook for Faculty. http://eric.ed.gov/?q=ED317097&id=ED317097.

- Angelo, T., & Cross, K. P. (n.d.). Teaching Goals Inventory, Self-Scorable Version. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from http://www.tusculum.edu/adult/learning/docs/TeachingGoalsInventory.pdf.

- Or review other transformational learning goals – discussed in A3.

- You may also want to read about motivation, epistemology, and other theories discussed in Unit A.

Outcomes do not have to be specific, but they will lead to specific objectives.

Worksheets in Chapter W2 may help you identify your learning outcomes.

Learning Outcomes vs Learning Objectives

Unfortunately, the definitions for learning goals, outcomes, and objectives are not universal across universities or even within a campus. Your accrediting agency may use them differently as well! The following definitions describe how these terms are used in this workbook:

- Learning outcomes refer to the large or overarching goals you have for your course.

- Learning objectives – Here, we use this term to mean the more concrete or specific goals which make up a learning outcome. So, for each learning outcome, you likely will have several learning objectives.

Chatterjee & Corral (2017) explain the difference between the levels here (note that this article refers to learning goals, while the IDI model uses the term learning outcomes): (Skip)

An anesthesiologist starts his grand rounds presentation on the topic of malignant hyperthermia (MH) with the following learning objectives:

- Understand the pathophysiology of MH.

- Review the clinical presentation of MH.

- Discuss the treatment of MH.

- Become familiar with caffeine-halothane contracture testing for MH.

This list informs the attendees about the topics covered during the presentation. However, do they know what is expected of them when they apply this content in their own clinical practice? We have all seen learning “objectives” mentioned, such as the ones above, at the beginning of a presentation or workshop. But is what we see actually a learning objective? Learning objectives are often confused with learning goals [or outcomes]; the example above is such a case in point. Learning goals [or outcomes] are related to—but different from—learning objectives. A learning outcome is a broad statement of an expected learning goal of a course or curriculum. Learning goals [outcomes] provide a vision for the future and often summarize the intention or topic area of several related learning objectives. Learning objectives are drawn from the learning goals [outcomes]. They are guiding statements for each learning encounter, and they connect intention with reality within the learning experience as well as to the assessment planned.

Writing Learning Outcomes

Outcomes are not as specific as objectives and usually cannot be measured directly.

- For each outcome topic, write an outcome statement that includes descriptive, integrated, holistic and enduring characteristics.

- Word your learning outcomes as warm and positive such as “We will…” (Supiano, 2021).

- Map your outcomes using worksheets in step 2 (use Chapter A6 to identify which of Bloom’s taxonomies are involved and which categories/levels of each. This will help you when writing learning objectives.

Fowler (2016) describes the format in more depth:

Descriptive: They describe the specific dimensions of what a student should know and be able to do, and what dispositions they should embody. Integrated: They integrate multiple dimensions of performance. Outcomes are not simply stated as: “student follows x procedure to create product y.” Rather, outcomes are stated in terms of complex performances acknowledging that there may be many solutions, procedures or skills students can integrate as they solve real problems. Holistic: Related to the above, outcomes are written to encompass the comprehensive aspects of a performance, identifying the specific criteria under which a performance is “successful.” Enduring: Generally speaking, the ultimate aim of any educator or educational institution is to help students develop traits or qualities that remain with them beyond graduation. Outcomes are written to apply to a variety of settings, not just to accomplish a specific task in a course.

Table 4: Example outcomes from Fowler (2016)

| Non-Example | Example |

| Evaluate a business plan | Evaluate business strategies for their relevance to and appropriateness for international standards of practice. |

| Differentiate between mitosis and meiosis and describe the importance of each. | Explain the importance of mitotic cell division in genetic variation. |

Writing Objectives

Tone

Supiano (2021) reports that research shows a warm tone is better received by students and “makes students more likely to reach out for help.”

For this reason, the traditional wording of objectives is changed a little here. Instead of the traditional:

“At the end of (TIMEFRAME such as course, unit), the student will be able to (ACTION VERB) to (EXTENT, SUCCESS LEVEL, etc.), under (CONDITIONS).”

Based on Supiano’s recommendation:

“At the end of (TIMEFRAME such as course, unit), we will be able to (ACTION VERB) to (EXTENT, SUCCESS LEVEL, etc.), under (CONDITIONS).”

While this may seem a small change, students who read these are more likely to reach out for help than students who read the syllabus section about available help.

Format

For each outcome, you will have several objectives. Objectives need to be measurable, so you and your students understand clearly when they have met the objective. Use Bloom’s Taxonomies to determine what level of learning you are aiming for, then use that again to identify an appropriate verb. Bloom’s Taxonomies are included in chapter A6, but a printable copy is available in the Appendices, References, & Indices.

Objectives are more specific than outcomes and leave little room for interpretation (so, for example, various instructors using the same objectives should evaluate student success the same way). Many instructors find that writing clear objectives helps them better understand exactly what they need to teach and, often, how to teach that objective. For example, an instructor once told me that he didn’t understand why students performed so badly on his tests until he clarified his objectives: he then realized that he was teaching one level of knowledge but testing at another! By ‘level’ he was referring to Bloom’s taxonomy categories. Clear objectives helped him identify what he wanted his students to accomplish and also helped him identify how to accurately measure just that.

According to Mager (1997):

- An objective is a description of a performance you want learners to be able to exhibit before you consider them competent.

- An objective describes an intended result of instruction, rather than the process of instruction itself.

And the components are (Wikiversity, 2018):

- Performance: The objective should describe what the participant should be able to do; also referred to as behavior and includes an action verb.

- Condition: The objective should describe under what constraints the participant’s performance occurs. This includes length of time, specific circumstances, etc.

- Criterion: The objective should determine at what point the performance is acceptable; it describes the standards that must be met, such as the extent, success level, etc.

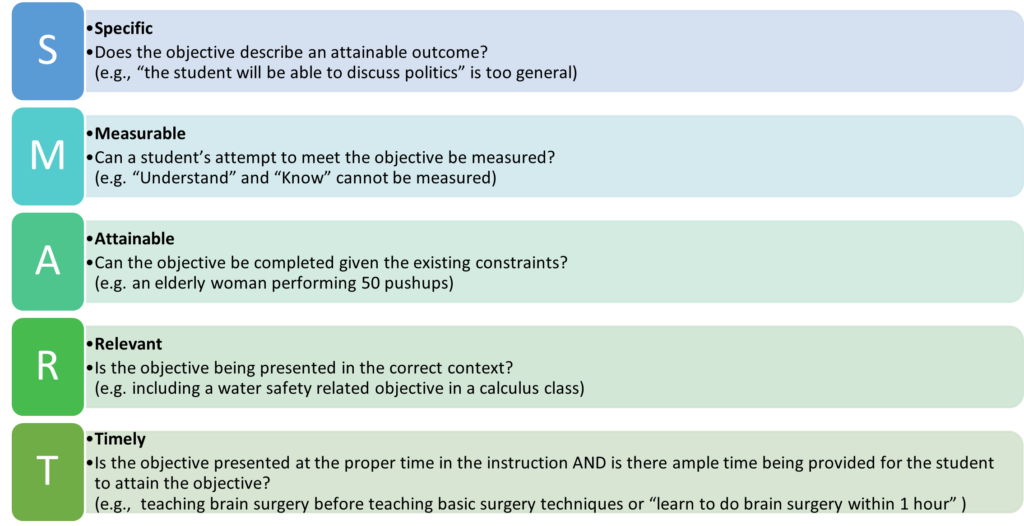

SMART Objectives

You can test your objectives against the SMART criteria (See Figure 3). Ensuring that your objectives are SMART will help you later:

- In the design, development, and teaching of your course, particularly when writing assessments.

- In discussions about assessment expectations and results with your students.

Examples Of Objective Verb Selection

The University of Arkansas provides the following examples and explanations (Shabatura, 2020). Note that these objectives do not include the conditions or timeframes. They are emphasizing the verb selection.

Original version: Understand immigration policy. How can we improve this? Understand is not a measurable verb. A conversation with this instructor revealed that she was really wanting to focus on historical aspects. These are things her students would be able to describe, which is measurable. Revised version: Describe the history of American immigration policy. Original version: Formulate a management plan for each of the above. How can we improve this? The instructor intended this objective to be third of fourth on a list. However, each objective must stand alone without reference to other objectives. Revised version: Develop a management plan for the four commonly found greenhouse pests of tomatoes–aphids, fungus gnats, white-flies and scale.

Figure 3: SMART Criteria for Objectives

Table 5: Examples of SMART Objectives from Chatterjee & Corral

Chatterjee & Corral (2017) provide examples from a medical field (Skip).

| Weak learning objective | SMARTer learning objective | Explanation |

| Review the anesthetic considerations in pediatric traumatic brain injury. | Formulate an anesthetic plan for a child presenting with abusive head trauma that includes the following steps from the 2012 guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children and adolescents with 80% accuracy: rapid sequence induction, in-line cervical stabilization for intubation, maintain normocarbia, avoid hyperthermia, avoid hypotension, treat seizures, monitor intracranial pressure and treat intracranial hypertension. | Verbs such as review, understand, appreciate, learn or become familiar with are not measurable or observable and should be avoided. |

| Be aware of anesthetic considerations with neurophysiologic monitoring in spine surgeries. | Accurately compare the effects of at least three intravenous anesthetic agents on the latency and amplitude of somatosensory and motor evoked potentials for neurophysiologic monitoring during posterior spinal fusion. | Even though the context is dearly stated, ‘be aware of’ is not measurable or observable. |

| Discuss possible complications during open mid-gestation fetal surgeries. | Critically analyze the risk of preterm labor, preterm premature rupture of membranes and uterine dehiscence following open mid-gestation fetal myelomeningocele repair in the Management of Myelomeningocele Study. | Analyze is a higher order cognitive skill than discuss. |

| Describe the anesthetic implications of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in a former premature infant. | Perform a preoperative evaluation of a former premature infant with bronchopulmonary dysplasia who is scheduled for emergency inguinal hernia repair that includes a detailed history, lung auscultation, measuring baseline oxygen saturation, administering preoperative bronchodilators and ruling out concurrent pneumonia, within 30 minutes. | Evaluate is a higher order cognitive skill than describe. |

Writing Objectives

Unit W has series of worksheets to help you identify and write your outcomes and then your objectives. However, if you want more help, see this website which has a tutorial: Instructional design/Learning objectives: Wikiversity (2014) http://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Instructional_design/Learning_objectives.

Sequencing Outcomes & Objectives

Your learning outcomes may suggest a natural sequence to you. For example, Frank Dooley’s AGEC 20300 course includes the following three learning outcomes (among others):

- Master the language (jargon and terminology) of economics.

- Be able to create, interpret, and understand key economic graphs.

- Develop an understanding of economic theory, especially price and output determination, elasticity, cost theory, and production theory.

It would be difficult for students to complete number 4 without first completing number 3. In turn, number 5 is dependent on number 4.

Sometimes the sequence for your outcomes will be obvious. For example, before students can balance a bank statement, they must have particular math skills, spreadsheet skills, and banking terminology, to name a few (These may be called pre-requisite objectives).

In other instances, however, you may find that the sequence is less obvious, and so you may want to consider some other rationale for sequencing outcomes. For example, going from a general concept of the components of something before building a comprehension of that topic might be an option. But reversing the sequence to develop comprehension and then analyze the components might also work.

When defining your sequence, consider scaffolding – building on existing student schemas.

Your outcomes need to be sequenced based on a logic such as:

- simple SKAs to complex SKAs

- general to specific,

- specific to general,

- early to late (for example, history courses typically start back in time and move forward),

- small to large,

- large to small,

- another sequence that will make sense to your students.

IDI & Course Outcomes & Objectives

Although learning outcomes and objectives are developed and written in the first two steps, they will influence all steps in the IDI model. The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from outcomes & objectives in the IDI model:

Step 1. Where are You Starting?

1.1 Review Course Requirements

- Check the course and program descriptions for required learning outcomes.

- Check for accreditation requirements that might be included in your course.

- Identify which courses require learning outcomes from your course (where your course is a pre-requisite).

- Check if your program committee identified any threshold concepts that you need to consider.

- Consider threshold concepts, metacognition, cognitive load, inclusivity, and other concepts for ideas of other goals. Review the Teaching Goals Inventory (Angelo & Cross, 1993).

1.2 Identify Student Learning Characteristics

- How might the student characteristics impact their mental models – epistemological level (Chapter A7), mental schemas and ability to accept threshold concepts (Chapter A2), etc.?

Step 2. Where are You Going?

2.1 Write Learning Outcomes & Objectives

- Write your learning outcomes using worksheet 2.1a – Outcomes.

- Write your learning objectives using worksheets 2.1b -Measurable Objective Format and 2.1c –Outcomes to Objectives.

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- For each assignment and assessment, check which outcomes and objectives they work toward (Worksheet 3.1c – Assessment Summary).

- When identifying student readings, match them to outcomes and objectives (Worksheet 3.1e – Selecting Student Readings)

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.1 Develop & Teach Course

- Check your class outlines to make sure they are aligned with the outcomes and objectives (Worksheet 4.1a – Class Outline).

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Use the class outline to note how various activities worked toward achieving the course outcomes.

References

Angelo, T. A., & Cross, K. P. (n.d.). Teaching Goals Inventory. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from https://tgi.its.uiowa.edu/ (provides automated reports).

Angelo, T., & Cross, K. P. (n.d.). Teaching Goals Inventory, Self-Scorable Version. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from http://www.tusculum.edu/adult/learning/docs/TeachingGoalsInventory.pdf.

Angelo, T., & Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Assessment and Reaffirmation of Foundational Oral Communication Outcome. (n.d.). Purdue University. Retrieved June 1, 2010, from https://www.purdue.edu/provost/students/s-initiatives/curriculum/documents/hle-found-learn-oc-example-.pdf.

Berrett, D. (2012, February 19). How “Flipping” the Classroom Can Improve the Traditional Lecture. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/How-Flipping-the-Classroom/130857.

Chatterjee, D., & Corral, J. (2017). How to Write Well-Defined Learning Objectives. The Journal of Education in Perioperative Medicine : JEPM, 19(4). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5944406/.

Cross, K. P., & Angelo, T. A. (1988). Classroom Assessment Techniques. A Handbook for Faculty. http://eric.ed.gov/?q=ED317097&id=ED317097.

Expected Outcomes—Office of the Provost—Purdue University. (n.d.). Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://www.purdue.edu/provost/students/s-initiatives/curriculum/outcomes.html.

Fowler, G. (2016, March 8). Student Learning Outcomes: A Primer. OLC. https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/student-learning-outcomes-primer/.

Mager, R. F. (1997). Preparing Instructional Objectives: A Critical Tool in the Development of Effective Instruction (3 edition). Center for Effective Performance.

Program: Communication, BA – Purdue University—Acalog ACMS. (n.d.). Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://catalog.purdue.edu/preview_program.php?catoid=10&poid=15700&returnto=13443.

Rhodes, T. (2010). Assessing outcomes and improving achievement: Tips and tools for using rubrics. Association of American Colleges and Universities. https://www.aacu.org/value/rubrics/oral-communication.

Shabatura, J. (2020, April 28). Learning Objectives: Examples and Before & After. University of Arkansas, TIPS for Teaching with Technology. https://tips.uark.edu/learning-objectives-before-and-after-examples/.

Supiano, B. (2021, March 25). Teaching: How Your Syllabus Can Encourage Students to Ask for Help. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2021-03-25.

Wikiversity. (2018, May 29). Instructional design/Learning objectives. https://en.wikiversity.org/wiki/Instructional_design/Learning_objectives.