C. Teaching Practices

C7. Assessments & Activities

- Assessments & Activities

- Grading Schema

- Learning Activities

- Getting Students to Come to Class Prepared

- Online Student Labs

- Lists of Activities

- Homework Time Estimates

- Student Projects

- Student Project Management

- IDI & Assessments

- References

Assessments & Activities

You can use projects, quizzes, portfolios, tests, and other activities for student assessment. Below, instead of saying ‘activities and assessments’, we are using the term ‘assessments’ to refer to any type of assessed work.

You can use activities throughout the course that do not ‘count’ for assessment purposes, such as think-pair-share, jig-saws, muddiest points, etc. These are usually short, lasting only one or two sessions.

Uses For Assessments

Student assessment is a critical part of university teaching. For students, assessment provides an awareness of how well they are understanding and learning what is expected. For instructors, assessment can provide an awareness of student learning gaps and progress. For the institute, a student’s final grade provides important tracking for measuring student (and instructor and institute) progress.

You can use diagnostic assessments at the beginning of a course term to determine a starting point for the course. Formative assessments can be used to determine how well students are progressing toward the course’s learning outcomes and as interim/benchmarks for students. Summative assessments are usually used to formally grade students’ ability to complete the learning outcomes. Some activities might be used for all three or for formative and summative, such as attitudes.

Diagnostic Assessments

At the beginning of a course, or sometimes the beginning of a new unit, a diagnostic assessment may be useful. Understanding your students’ basic current SKAs can help if your course is appropriate for them (too elementary or too advanced), if your course outcomes and objectives need some modification (students already have achieved some of the outcomes or some additional outcomes are needed), or if some students need additional support. This may be particularly appropriate in introductory level courses or courses where students might be coming from a variety of majors and backgrounds.

Examples:

- A business course may require that students are able to use advanced Excel features to which few students have been exposed

- A communications course may include a unit on Mayer’s 12 principles for designing multimedia, but most students have already achieved the required level of knowledge

- A chemistry course may require knowledge and application of math concepts that some of your students do not have

A diagnostic assessment can help identify either a starting point for your course, modification of some units, or the need for some additional student work (such as study sessions on specific topics, student support services, study skills tutorials, etc.).

Results of Diagnostic Assessments

Before you give a diagnostic, determine what you will do if some or all students are not proficient.

- Can you refer them to resources, such as a math tutorial, confident that it will provide the needed background or does your institution provide student tutoring that would provide proficiency? If yes, will the students be able to acquire the proficiency required before your course unit that requires it?

- Do you have the resources to include new objectives within your course?

- Can you advise non-proficient students to drop your course and add a prerequisite? What course(s) would meet these needs?

- If students take another course along-side yours, would that give them proficiency at the right time needed? What course(s) would meet these needs?

Diagnostic Assessment Contents

To identify possible student SKA gaps:

- Use worksheet 2.1b -Measurable Objective Format to identify prerequisite skills and identify how students should have been exposed to these.

- Review your student demographics to determine likelihood that students have the prerequisite. Based on how important the prerequisite is, determine if you need to identify current student achievement on this.

- If this is important, identify methods to check their current abilities (do they need to answer some questions, do they need to complete a task…).

To identify possible areas of expertise that you do not need to include in your course:

- Reviewing your sequence of outcomes, consider which ones students might be most likely to have experienced.

- Identify methods to check their abilities (do they need to answer some questions, do they need to complete a task…).

Formative Assessments

Often there is a gap between what is taught and what is learned. Formative assessments provide you information about needed additional teaching and students with awareness of what they do not know. Some formative assessments may be also used for summative assessment, such as points for drafts of a project or quizzes.

Summative Assessments

A summative assessment can be used as the only determinant of students grades or as a high-value assessment. In the past, instructors used exams (multiple choices, true/false, short answer, and essay questions) for summative assessment. However, activities such as individual and group projects, case studies, and product development etc. are being used more as they also promote learning at higher levels on Bloom’s Taxonomies.

As with formative assessments, summative assessments should be directly related to your course outcomes and objectives using the worksheets mentioned.

Writing Up Formative & Summative Activities/Strategies

Students need details for each activity. You can use some of the worksheets in the Identify Activities section of Unit W to ensure you have accurate and appropriate details.

All activities, assessments, and assignments should be directly related to your course outcomes and objectives. To help you align these, you may want to complete the assessment map worksheet 2.1c –Outcomes to Objectives.

Introducing the Activity

Although you may provide an excellent written description, students also need to hear about it and have an opportunity to ask questions.

- Do not read the instructions.

- Start with a brief description of the activity and its purpose, giving the course outcomes that are involved.

- If this is a group activity, you may note that students will start looking for others to form groups. Tell them early if you have assigned groups. Explain “When you work in the real world, you work with whoever you have to work with, and you don’t choose your buddies” (Holland, 2019, p.313).

- Provide a synopsis of the activity.

- Discuss formats for the final product (is it a simple read-out, a butcher-paper list, etc.).

- Discuss in-class time and out-of-class time expectations.

- Ask students if they have questions.

- After the students have started the activity, check with each team for questions and problems.

Grading Schema

Your course will have an assigned grading option such as pass/fail, A through F, or satisfactory/unsatisfactory. Within this, you have options for how you determine grades.

Points – One of the most common methods is to assign the maximum number of points to each assignment and assessment. You then add up all the maximum points to determine the maximum possible for the course and plot those onto the grading option.

Percentages – you may also assign percentages to each assignment and assessment. Once you have them equaling 100%, it is relatively easy to plot these against the grades. This is often easier than trying to assign points to a grade scale.

Using the LMS for grading – most LMSs provide a grading center which you can use to work out grades. At the beginning of the term, you can enter the percentages per activity & assignment, then as the term progresses, enter the percent each student achieved. The students can see these and see their progress.

Some Notes on Grades

Under the assumption that we want ALL our students to succeed in our course, here are a few considerations:

Diagnostic, formative, and summative assessments might be norm-based, comparing a student to a ‘norm’ group, or criterion-referenced, comparing a student to the course outcomes and objectives.

Curved Grading – Don’t. This is one form of norm grading where you compare the success of one student against all the other students in the class.

- You are then pre-determining that a specific number of students will succeed (regardless of their actual ability to achieve the outcomes), and that other students will not succeed (regardless of their ability to meet outcomes).

- Grading on a curve is also assuming that THIS class of students compares favorably with other classes of students; a student earning an A grade this year is achieving the same level of performance as past students and students in this class section are performing the same as students in other sections.

- If you grade on a curve, you are asking the students to compete with each other. This can provide motivation for students who typically win in a culture focused on individualism. Students from other cultures and students who typically do not win (often those with disabilities and students of color, for example) may be demotivated. To provide a safe and community-minded classroom, you should not grade on a curve (Perez, 2020).

Improvement grading – if you grade based upon how much a person has improved, you risk giving a passing grade to a student who still has not mastered the content. However, in some cases this is perfectly correct. Portfolios are a good method of doing this.

Points for Participation – if you feel student participation in discussions and activities is valuable and supports all students, then provide points to encourage students (you may want to use additional techniques, such as those in the Class Discussions section).

Group Activities – if you want students to participate in groups, provide peer assessments and use them in grading.

Multiple Choice & True/False – these types of questions are good for when students need to have memorized information or need to be able to define information and its characteristics. Writing these questions to test HOTS is difficult, but not impossible. They are also usually not appropriate for checking HOAS and HOPS. Although they are harder to grade, short answer and essay tests are usually better at higher-order SKAs.

Portfolios – portfolios are a collection of student work over the term. Usually, students are allowed to select what is in their portfolio, giving them a chance to show what they consider their best work. You can still have regular assignments that are reviewed and provide feedback (using Hattie’s model) to help students improve. Many students will be required to build a portfolio for job interviews, such as teachers, and some colleges require a portfolio for graduation.

Rubrics – Providing students with a rubric will 1) provide them with guidance on what to write and how, 2) provide you with easier and faster grading, 3) provide better feedback to students on where they can improve.

Peer assessments – if you are going to use peer assessments as part of the grading scheme, make sure you provide a rubric. Peer assessments can support critical thinking, language skills, and team building. Although you should share assessment information with the student, this should be kept anonymous.

Some Creative Options for Grading Assignments & Assessments

- Create assignment/course rubrics with students (Spangler, n.d.)

- Have students fill in evidence of learning on their assignment/course rubric (Spangler, n.d.)

- Grade with students in grading conferences (Spangler, n.d.)

- Dropping a grade – see the following articles:

- Skinner, N. F. (2015). Dropping Scores: The Case for Hope. Faculty Focus. http://info.magnapubs.com/blog/articles/educational-assessment/dropping-scores-the-case-for-hope/

- Weimer, M. (2015). Calculating Final Course Grades: What about Dropping Scores or Offering a Replacement? Faculty Focus. http://info.magnapubs.com/blog/articles/educational-assessment/calculating-final-course-grades-what-about-dropping-scores-or-offering-a-replacement/

Role of Feedback

Formative and summative assessments without effective feedback are unlikely to result in positive student improvement. “The goal of formative assessment is to monitor student learning to provide ongoing feedback that can be used by instructors to improve their teaching and by students to improve their learning” (Eberly Center, n.d.). For details on feedback types and methods, see Chapter C10.

Learning Activities

Literally hundreds of assignment and assessment types are available. Selecting an appropriate assessment depends on the learning objective(s) you are trying to measure, your learning model, the time available to both administer and evaluate the assessment, the equipment needed, your students, etc. When selecting a strategy, remember to check it against your course outcomes and objectives to ensure it also matches the needed types and level of Bloom’s Taxonomies using the assessment map worksheet 3.1c – Assessment Summary.

The following lists of activities, available online, are divided into 1) sites listing activities that are designed for classroom, 2) sites listing activities designed for both classroom and distance/online, 3) sites listing activities that recommend student technologies, and 4) sites listing a combination of activities, some of which are online and some classroom. With revision, most can be adapted to other modes.

For all activities, determine if they are complex enough that you will need an activity description sheet for students.

Getting Students to Come to Class Prepared

Unprepared students can negatively impact a class in many ways. They may be unable to participate in discussions, they may ask questions that are answered in the homework, and they may slow down group work and activities.

Here is a list of strategies to motivate such students:

- Develop a series of online pre-class quizzes specifically on the readings, video-lectures, etc. (This will also help you identify problem-areas in the subject).

- Assigning points for completion will incentivize students to complete the quizzes.

- “In many cases, grading for completion rather than effort can be sufficient, particularly if class activities will provide students with the kind of feedback that grading for accuracy usually provides” Brame (2013).

- Weinstein and Wu (2009) (as cited in Weimer, 2012) suggest “Readiness Assessment Test” (“RAT”) quizzes: 2 or 3 open-ended questions ‘to prevent students from skimming though the readings in search of answers to detailed questions.’…Answers to these questions were graded, with each answer earning up to four points.”

- Make sure your homework is reasonable. (See Homework Time Estimates below)

- Let students know your turn-around time for homework and stick to it.

- In small classes, begin by requiring that each student ask at least one relevant question related to the reading and/or lecture material.

- Refer to and/or discuss the readings during class. Often students will feel reading material will just be covered in class. Use readings as additional material and use them to build on the class content.

- Include information from homework in the quizzes and tests.

- Start class by asking questions answered in the homework:

- Ask students to write their answer then pair up (or other think-pair-share method)

- Divide students into groups of 3 or 4 and assign each group different questions, then have them “jigsaw” – a member of each group joins with members of others and reviews their Q&As

- Divide the students into groups and assign a spokesperson to report back on their group discussion

- Using a polling program to collect student answers – this can then be displayed, and students grouped to discuss different answers

More on RATs

Although the research on RATs is limited, Weinstein and Wu (2009) (as cited in Weimer, 2012) found:

- Completion of readings increased significantly

- Students preferred RATs (56% compared to 33% who preferred normal quizzes)

Online Student Labs

With the use of technologies, even labs can be virtual. Subjects such as physics, chemistry, math, earth science, and biology can be completed using virtual simulations. Refer to Badillo (2020) for more. Several companies are now making lab kits that can be sent to student homes for ‘kitchen labs.’ For more information on these, check journals and magazines in your discipline.

If you are interested in adopting a virtual or kitchen lab for your course, be aware that there are additional costs and other considerations (such as liability) that may require discussions with your institution’s department, IDs, and perhaps legal team.

Lists of Activities

1) Activities Designed for Classroom

Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching (CELT). (n.d.). 226 Active Learning Techniques. Iowa State University. https://www.celt.iastate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CELT226activelearningtechniques.pdf

226 activities categorized by:

- Lecture,

- Lecture (Small Class Size),

- Student Action: Individual,

- Student Action: Pairs,

- Student Action: Groups,

- Second Chance Testing,

- YouTube,

- Mobile and Tablet Devices,

- Audience Response Tools,

- Creating Groups,

- Icebreakers,

- Games (Useful for Review),

- Interaction Through Homework,

- Student Questions,

- Role-Play,

- Student Presentations,

- Brainstorming, and

- Online Interaction.

Each activity includes a brief description.

Cross, K. P., & Angelo, T. (1988). Classroom Assessment Techniques. A Handbook for Faculty. http://eric.ed.gov/?q=ED317097&id=ED317097

50 assessments, commonly known as 50 CATS (Classroom Assessment Techniques). These are targeted at individual student activities; however, some can be easily adapted for pairs or small groups. Although listed as assessment techniques, all of these involve students thinking about their learning. These are categorized by sub-areas within the following Areas for Formative Assessment:

- Course- Related Knowledge and Skills

- Prior Knowledge, Recall, and Understanding

- Skill in Analysis and Critical Thinking

- Skill in Synchesis and Creative Thinking

- Skill in Problem Solving

- Skill in Application and Performance

- Learner Attitudes, Values, and Self-Awareness

- Students’ Awareness of Their Attitudes and Values

- Students’ Self-Awareness as Learners

- Course-Related Learning and Study Skill, Strategies, and Behaviors

- Learner Reactions to Instruction

- Learner Reactions to Teachers and Teaching

- Learner Reactions to Class Activities, Assignments, and Materials

These are cross-referenced under 6 teaching goal categories: 1. Higher-Order Thinking Skills 2. Basic Academic Success Skills 3. Discipline Specific Knowledge and Skills 4. Liberal Arts and Academic Values 5. Work and Career Preparation 6. Personal Preparation Each CAT includes the following sections: • description, • purpose, • suggestions for use, • example, • procedure, • analyzing the data you collect, • ideas for extending and adapting, • pros & cons, and • caveats. For a spreadsheet cross-referencing the CATS to each of the categories, please see (Reid, n.d.): https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1NAIxhpdmS0MVONw6Zzb9kutBdBouGhM8w4CqFLFlTDI/edit#gid=0

Purdue Writing Lab. (n.d.). Purdue OWL // Purdue Writing Lab. Purdue Writing Lab. Retrieved September 17, 2022, from https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/purdue_owl.html

In addition to guidelines on proper referencing for various style (such as APA and MLA), the Purdue OWL provides a guide on how to avoid plagiarism and guides for students on: • Professional, Technical Writing • Writing in Literature • Writing in the Social Sciences • Writing in Engineering • Creative Writing • Healthcare Writing • Journalism and Journalistic Writing • Writing in the Purdue SURF Program • Writing in Art History

Supplemental Instruction. (n.d.). Active Learning Strategy Cards. DePaul University. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://resources.depaul.edu/teaching-commons/teaching-guides/learning-activities/Documents/Strategy%20Cards%207.25.16%20MASTER.pdf

70 strategies, categorized by level of Bloom’s Cognitive Taxonomy and by the following: • Facilitation Techniques, • Recall/Review Activities, • Organization and Visuals, • Problem Solving Activities, • Study Strategies, and • Growth Mindset. The list provides basic directions for each strategy.

2) Strategies That Include Directions for Online and Distance Use

Baumgartner, J. (n.d.). Active Learning while Physically Distancing. Louisiana State University. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from Active-Learning-while-Physically-Distancing-Louisiana-State-University.pdf

22 strategies with directions for using each in: • Online—Synchronous, • Online—Asynchronous, and • F2F Physically Distanced modes. This Google sheet includes links to useful documents and technologies to support each strategy. The strategies are organized in the following categories: • Engage Content Learning + Support Communication Skills Development, • Engage + Check Understanding, • Monitor/Assess Understanding, • Reflect on Learning, • Strengthen Understanding, • Active Engagement + Planning for Future Learning Connections, and • Providing/Getting Feedback on Work in Progress. (A slightly different version of this list is available at: https://trefnycenter.mines.edu/active-learning-in-remote-virtual-hybrid-online-and-physically-distanced-classrooms/)

Center for Teaching Innovation. (n.d.). Active Learning in Online Teaching. Cornell University. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://teaching.cornell.edu/resource/active-learning-online-teaching

18 strategies specifically for online learning, including links to technologies to support each. Organized into the following strategies: • Practice with Feedback, • Peer Learning, and • Structure. This webpage also includes sections on • Some challenges encountered when doing active learning online and • Putting it all together: Cornell courses using active learning online.

Teaching Techniques for Higher Education. (n.d.). The K. Patricia Cross Academy. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://kpcrossacademy.org/downloads/

50 strategies (including some from the original CATS, but many new) providing both online and classroom directions. Categories: • Active/Engaged Learning (39) • Discussion (2) • Games (20 • Graphic Organizing (6) • Group Work (11) • Learning Assessment (17) • Note Taking (4) • Presentation (4) • Problem Solving (4) • Project Learning (6) • Reading (2) • Reciprocal Teaching (9) • Reflecting (10) • Writing (16) Each strategy includes activity type, teaching problem addressed, learning taxonomic level, step-by-step instructions, support materials, variations and extensions, instructor’s technique template, example, references and resources. Each activity has a separate download. For online adaptation information, refer to the videos at their website.

3) Strategies That Recommend Student Technologies

(These are also listed by Taxonomy Level)

Carrington, A. (2016). The Padagogy Wheel English V5. In Support of Excellence. https://designingoutcomes.com/english-speaking-world-v5-0/

Although this primarily provides a list of technologies for completing student activities, it also provides a long list of types of assignments many of which can be completed without technologies. The Padagogy Wheel is sorted by both Bloom’s Cognitive Taxonomy and the SAMR Model. For each of the Cognitive and SAMR levels, it provides: • A list of action verbs • Activities for each level • Technologies which may be used by students to complete the activities While the Padagogy Wheel provides a handy verbs and activities list, some people find difficult for technology selection as the technologies are not directly linked to each activity. For those with a knowledge of the technologies and those who enjoy reviewing various technologies, however, this works well.

Churches, A. (2008). Bloom’s digital taxonomy [PDF]. Retrieved 11/11/2022 from https://louisville.edu/delphi/resources/-/files/resources/pages/Blooms-Digital-Verbs.pdf

This first lists action verbs for each level of Bloom’s cognitive taxonomy specific to digital learning. It then provides a list of digital tools for each verb. For example, Creating: New Game > Gamemaker, RPGmaker and Evaluating: Report > Word Processing or web published – Report, blog entry, wiki entry, web page, DTP, Presentation, Camera.

Schrock, K. (n.d.). Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Everything. Retrieved September 17, 2022, from https://www.schrockguide.net/

Provides strategies and links to other websites categorized by: • Assessment • Creativity • Devices • Emerging Technologies • Information/Digital Literacy • Pedagogy • Professional Growth This includes a page called Bloomin' Apps, listing activities tied directly to apps, sorted by Bloom’s Cognitive Taxonomy and by iPad, Android, online, and G suite. Six tools are provided for each level for iPad and Android app, and five per level for online and G Suite. Links for each app are provided. Another page, Activating Strategies for Use in the Classroom, provides 48 strategies with brief descriptions.

4) Lists of a Combination of Activities

Discipline Specific Activities

MERLOT. (n.d.). Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.merlot.org/merlot/

According to the MERLOT website (n.d.), “The MERLOT system provides access to curated online learning and support materials and content creation tools, led by an international community of educators, learners and researchers.” Of particular interest: Academic Discipline Portals and Academic Support Portals which allow you to drill down to find resources appropriate for your class. This then provides links to the actual material.

Activities & Topics

Bonk, C., & Khoo, E. (2014). Adding Some TEC-VARIETY: 100+ Activities for Motivating and Retaining Learners Online. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. https://www.academia.edu/8067390/Adding_some_TEC_VARIETY_100_Activities_for_motivating_and_retaining_learners_online

Despite the title, this free, online book, includes activities which can be either online or f2f. A list of appropriate technologies, by category, is included at the end of the book. Note, however, that the book was written in 2014 and technologies may have changed. The activities are arranged in the following categories: 1. Tone/Climate: Psychological Safety, Comfort, Sense of Belonging 2. Encouragement: Feedback, Responsiveness, Praise, Supports 3. Curiosity: Surprise, Intrigue, Unknowns 4. Variety: Novelty, Fun, Fantasy 5. Autonomy: Choice, Control, Flexibility, Opportunities 6. Relevance: Meaningful, Authentic, Interesting 7. Interactivity: Collaborative, Team-Based, Community 2. Engagement: Effort, Involvement, Investment 3. Tension: Challenge, Dissonance, Controversy 4. Yielding Products: Goal Driven, Purposeful Vision, Ownership Each activity includes: • Description and Purpose of Activity • Skills and Objectives • Advice and Ideas • Variations and Extensions • Key Instructional Considerations • Risk • Time • Cost • Learner-centered • Duration of the learning activity

Ed Tech Deck. NWACCo. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.nwacco.org/

“The Ed Tech Deck is a collaborative effort featuring contributions from Instructional Technology staff from NWACC schools. Our goal was to create an instructional and technological resource for Faculty, with a physical deck for a quick introduction or overview for a topic, and a corresponding website for expanded information and links” (NWACCo, n.d.). Currently about 60 cards are available. Cards present a wide range of topics such as cloud storage, presentation tips for students, screencasting, and augmented reality interactive storytelling. Each card includes: • Description • Purpose • Procedure • Considerations • Level • Resources Cards can be searched and filtered by the following categories: • Cool tools and apps • Digital citizenship • Digital literacy • Instructional tech roundtable • iPad apps • Jobs

Teaching Techniques for Higher Education (n.d.). K. Patricia Cross Academy. Retrieved 11/13/2022 from https://kpcrossacademy.org/.

The Cross Academy offers 50 classroom techniques: “Whether you find yourself teaching online, on-site, or a hybrid of both, our free teaching techniques are focused on helping your students learn and retain new knowledge and skills.” Each technique includes a video and a download of a worksheet and instructions.

The techniques can be filtered on various terms. (number in parenthesis indicates number of techniques for that item)

Activity Type

Active/Engaged Learning (39)

Discussion (2)

Games (2)

Graphic Organizing (6)

Group Work (11)

Learning Assessment (17)

Note Taking (4)

Presentation (4)

Problem Solving (4)

Project Learning (6)

Reading (2)

Reciprocal Teaching (9)

Reflecting (10)

Writing (16)

Teaching Problem Addressed

Cheating (5)

Insufficient Class Preparation (9)

Lack of Participation (11)

Low Motivation/ Engagement (23)

Poor Attention/Listening (14)

Poor Note-Taking (5)

Surface Learning (32)

Learning Taxonomic Dimension

(based on Fink’s taxonomy, discussed in Chapter A3)

Foundational Knowledge (26)

Application: Analysis and Critical Thinking (25)

Application: Creative Thinking (9)

Application: Problem Solving (11)

Integration and Synthesis (17)

Human Dimension (5)

Caring (20)

Learning How to Learn (24)

Problem-Based Learning Resources

The Problem-Based Learning Clearinghouse. (n.d.). Institute for Transforming University Education, University of Delaware. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.itue.udel.edu:443/pbl/problems

In addition to sample syllabi, exams, and rubrics, the clearinghouse has “a collection of problems that assist educators in using problem-based learning. …Teaching notes and supplemental materials accompany each problem, providing insights and strategies that are innovative and classroom-tested” (The Problem-Based Learning Clearinghouse, n.d.). These can be filtered by level, length, and the following disciplines:

Accounting

Aviation Science

Biological Sciences

Biotechnology

Business Administration

Chemistry

Chemistry and Biochemistry

Composition and Rhetoric

Economics

Education

English

Environmental Science

Faculty Development

Finance

Food and Resource Economics

Foreign Languages

Geography

Mechanical Engineering

Medical Education

Multidisciplinary

Nutrition

Nutrition and Dietetics

Physics and Astronomy

Plant and Soil Sciences

Political Science

Problem-based Learning

Psychology

Public Policy

Research Design

Science Education

Sociology

Statistics

Women’s Studies

Other Uses for a Discussion Forum

Question and Answer Forum – Macdonald (n.d.) suggests a forum where students post questions about course material. Macdonald instructs students to post their question and “articulate your thinking about the question: What do you know already? What is confusing you? If you had to answer this question right now, how would you answer?” Macdonald responds after at least one student has commented.

Prud’homme-Généreux (2021) wrote up alternate ideas for using online discussions, with purpose, description, tips, examples, and variations for each, and suggestions on tools that can support each idea. Many of these can be applied to either full class discussions or teams. The main 21 ideas are:

Apply Learning

- #Hashtag that Photo Safari – students post a photo related to a course concept. Other students then recommend hashtags for each picture.

- Virtual Scavenger Hunt – students do an internet search for examples of a concept. After these are posted, students collaborate and compare the examples.

- Guessing Game – students post a description or example of a concept without naming the concept. Other students try to name the concept.

- Forced Analogy – students try to compare a concept to an unrelated object.

- Flawed Design – “Learners design an example that is purposefully ‘broken’ and defies the concept learned in class.” Other students then identify the flaws.

Explore Concepts Through Divergent Thinking

- Sticky Note Party – (synchronous) (Requires virtual collaborative pinboard) based on a prompt, students each create a pile of virtual sticky notes with one idea on each. One-by-one, students present their ideas and other students add their similar ideas to it. Students then try to categorize the resulting piles.

- Wisdom of Crowds – (synchronous) (Requires virtual collaborative pinboard) to prioritize ideas, students start with a Sticky Note Party, then the group ranks the resulting piles.

- Lotus Diagram – (Requires virtual collaborative pinboard or presentation program) one group of students start a concept map for a concept, creating first-level ideas. A second group then adds secondary ideas, then a third group adds tertiary ideas. If using multiple concurrent concept maps, team discussion boards can be used for each concept.

- Mash-up – (synchronous) students define a problem then brainstorm to come up with an unrelated concept and brainstorm how the problem can be solved using the unrelated concept.

Explore Concepts through Convergent Thinking

- Report on Live Discussion – (synchronous) students share something personal (such as an experience). Students then write a reflection and post it.

- Give One, Take One – (Can use virtual collaborative pinboard or presentation program) Each student is given a prompt and 3-4 different statements that could be prompt responses. Students reflect on the statements then pair up to discuss which they agree with and why. They then exchange one statement. This is repeated three times then teams review and agree on five statements that the team holds to be true.

- Role Play – each student is assigned stakeholder role in a scenario. They discuss their motives, values, goals, etc.as the stakeholder (not as themselves).

- Jigsaw – (Team boards required for both initial and subsequent teams)Teams of students each become ‘experts’ in an aspect of a problem. New teams are formed with a member comprised of a member of each original team and the new teams try to solve the problem.

- Case Study – (Team boards required) students use a team discussion board to exchange ideas and negotiate how to solve a problem, how well the team’s solution works, etc.

- Round Robin – (Team boards required) given a discussion prompt, the first student starts an answer and next student completes the response, and starts a second response, etc.

- 3CQ Model – (Compliment-Connect-Comment-Question) each response must consist of each element of 3CQ.

Foster Metacognition

- Fishbowl – a small group of students participate in a discussion then the observers comment on the discussion.

- Role Swap – (Team boards required) each student is assigned a role such as facilitator, skeptic, fact checker and summarizer to help the discussion progress.

- Muddiest Points – students ask questions about what content is unclear. Use the questions to begin discussions.

- Karma Points – “Whenever learners want to recognize an idea that is noteworthy for inspiring and advancing their thinking, they can award “Karma Points” to the learner who made that post.” Points can be used in grading such as by a minimum to be considered good participation.

- Mood Board – (can use virtual collaborative pinboard or presentation program) (Separate board for each student) students create their own board of pictures, words, quotes, etc. that capture their feelings about the topic.

Homework Time Estimates

When you assign homework, consider the total workload – preparation, readings, and other assignments. The Carnegie guideline for student out-of-class work is 2 hours per credit hour each week. This includes preparation, reading, homework, etc.

Use a course workload estimator to determine if your combination of assignments and readings is appropriate:

- Rice University’s Course Workload Estimator – https://cte.rice.edu/workload (Course Workload Estimator, n.d.)

- Wake Forest University’s Enhanced Course Workload Estimator – https://cat.wfu.edu/resources/tools/estimator2/ (Barre et al., n.d.)

Student Projects

Individual Student Projects

(For group work, see Chapter C11)

A common student reaction to a major assignment can be complete bafflement on how to approach it. For many students, managing a project will be new.

If you have longer assignments for students, you may want to provide them with additional support. This can be in several forms:

- project management skills (project definition, task identification and scheduling, monitoring…)

- group management (stages of group forming, managing group members,…)

- product management (the actual results of the project, such as a written report, presentation…)

- decision making and problem solving processes (such as a Kepner-Tregoe model)

If you know a project manager, you may want to request that they present to your class. This can be over several sessions, scheduled to fit the project’s progress, such as:

- At the beginning, stakeholder and project definition, what is and is not included, etc.

- Project breakdown into tasks, assignments, dependencies, scheduling, etc.

- Risk and mitigation/management identification

- Monitoring and controlling progress, communicating with stakeholders

- Closing the project

Each of these can be a short presentation of the concept followed by students working on their projects.

Student Project Management

For major assignments which include stages, consider your students’ experiences in managing projects. Many may need help with developing a task list and timeline. You could ask an instructor from a local business school to give a presentation (your institution’s human resources team might also offer a workshop). Also consider giving your students project management forms. You can refer students to the following articles:

- Check your discipline’s journal and websites for free forms.

- If you do not have forms used within your discipline, review the free forms available from PBLWorks (https://my.pblworks.org/resources). This includes many resources for you on how to design a project assignment, but also 12 Student Handouts to help students manage their projects. Although these are designed for K-12 projects, they pretty much work for any HE term-long group work as well. If these do not seem appropriate for you, a Google search on “free project management forms for students” will provide you with many options.(n.d.)

- Benz, M. (n.d.)The Best FREE Google Project Management Apps Out There. Business 2 Community. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from https://www.business2community.com/strategy/the-best-free-google-project-management-apps-out-there-02177836.

- Esposito, E. (2020). The best free project management software in 2020. Zapier. https://zapier.com/blog/free-project-management-software/.

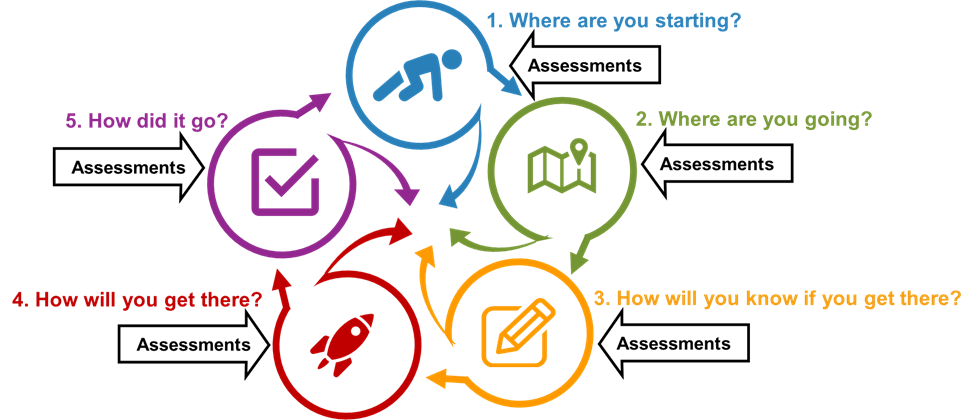

IDI & Assessments

The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from assessments in the IDI model:

Step 1. Where are You Starting?

1.1 Review Course Requirements

- Identify required grading schema.

1.2 Identify Student Learning Characteristics

- Determine what course and content your students have probably been exposed to.

Step 2. Where are You Going?

2.1 Write Learning Outcomes & Objectives

- Use worksheet 2.1b -Measurable Objective Format to identify prerequisite skills and identify how students should have been exposed to these.

- Review your student demographics to determine likelihood that students have the prerequisite.

- Reviewing your sequence of outcomes, consider which ones students might be most likely to have experienced.

- Based on what you expect as current student knowledge, determine what additional outcomes and objectives might be needed.

2.2 Finalize Learning Model

- Based on the desired assessments and activities, identify appropriate learning models.

- If your course has a lab section, consider what learning models might be appropriate.

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- Identify how you will grade student work (grading schema).

- Determine if you need a pre-assessment to identify current student knowledge.

- Identify student supports that might provide needed pre-requisite skills and knowledge.

- Create formative assessments to help you and your students understand their progress.

- Identify if you have long-term activities (such as projects) that will be used for assessment.

- Determine if you need a summative assessment or if an activity will provide the needed assessment.

- If you want a high-stakes summative assessment, develop it.

- Develop assessments that provide formative assessments and lead to success in the summative assessment or activity.

- Compare all assessments to the course outcomes and Bloom’s level, using worksheet 3.1c – Assessment Summary.

- Consider pre-session quizzes that check students understanding of the homework.

- Develop rubrics for all assessments which are used for formative and summative assessments.

- Add rubrics to your syllabus, or provide them as hand-outs, in the LMS, or some combination, but make sure students have them available.

- Based on all your assessments, including homework and discussions, determine points or percentages for each.

- Determine the value of each grade (A vs B, P vs F, etc.) and add this to your syllabus.

- Add all assessments, activities, and assignments to instructor’s schedule.

- Add appropriate assessments, activities, and assignments to students’ schedule in syllabus.

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.1 Develop & Teach Course

- Review course schedule, assessments, activities, and assignments designed in step 3 to determine what needs to be included in this session.

- Review the available activity lists to identify additional types of short activities which might be appropriate for your course at various points. (Note that these will probably not be used for assessment.)

- Use an activity to open each class session, based on the homework.

- Identify back-up activities in case one doesn’t work or the class has extra time.

- Pay attention to how activities are working to intervene if necessary.

4.2 Assess Students

- Use formative assessments and effective feedback techniques to support student growth and motivation.

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Use the class outline to note how well assessments supported student learning of the course outcomes.

References

All Resources | MyPBLWorks. (n.d.). Retrieved March 23, 2021, from https://my.pblworks.org/resources?_ga=2.171049956.576301045.1616508546-1448589906.1616508546&_gac=1.79634150.1616508546.Cj0KCQjwo-aCBhC-ARIsAAkNQiuX4XSNNDBw0Rc4W83zsy8lipb–MLG6pwAYkgjDOpzsIz4JJqrTZoaApiTEALw_wcB.

Badillo, J., Londino-Smolar, G., & Savvides, P. (2020). 7 Things You Should Know About Virtual Labs. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, 2.

Barre, B., Brown, A., & Esarey, J. (n.d.). Workload Estimator 2.0. Center for the Advancement of Teaching | Wake Forest Univesity. Retrieved April 6, 2023, from https://cat.wfu.edu/resources/tools/estimator2/.

Baumgartner, J. (n.d.). Teaching Tools: Active Learning while Physically Distancing. Louisiana State University. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from Active-Learning-while-Physically-Distancing-Louisiana-State-University.pdf (yorku.ca).

Benz, M. (n.d.). The Best FREE Google Project Management Apps Out There. Business 2 Community. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from https://www.business2community.com/strategy/the-best-free-google-project-management-apps-out-there-02177836.

Bonk, C., & Khoo, E. (2014). Adding Some TEC-VARIETY: 100+ Activities for Motivating and Retaining Learners Online. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. https://www.academia.edu/8067390/Adding_some_TEC_VARIETY_100_Activities_for_motivating_and_retaining_learners_online.

Brame, C. J. (2013, January 31). Flipping the Classroom. Vanderbilt University. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/flipping-the-classroom/.

Carrington, A. (2016, September 3). The Padagogy Wheel English V5. In Support of Excellence. https://designingoutcomes.com/english-speaking-world-v5-0/.

Center for Excellence in Learning and Teaching (CELT). (n.d.). 226 Active Learning Techniques. Iowa State University. https://www.celt.iastate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/CELT226activelearningtechniques.pdf.

Center for Teaching Innovation. (n.d.). Active Learning in Online Teaching. Cornell University. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://teaching.cornell.edu/resource/active-learning-online-teaching.

Churches, A. (2008). Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy. Unpublished Paper. http://burtonslifelearning.pbworks.com/f/BloomDigitalTaxonomy2001.pdf.

Course Workload Estimator. (n.d.). Rice University Center for Teaching Excellence. Retrieved March 23, 2021, from https://cte.rice.edu/workload.

Cross, K. P., & Angelo, T. (1988). Classroom Assessment Techniques. A Handbook for Faculty. http://eric.ed.gov/?q=ED317097&id=ED317097.

Esposito, E. (2020, September 29). The best free project management software in 2020. Zapier. https://zapier.com/blog/free-project-management-software/.

Holland, D. G. (2019). The Struggle to Belong and Thrive. In E. Seymour & A.-B. Hunter (Eds.), Talking about Leaving Revisited (pp. 277–327). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2_9.

Macdonald, S. (n.d.). Online Discussion Forums. Berkley University Graduate Student Instructor Teaching & Resource Center. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://gsi.berkeley.edu/gsi-guide-contents/technology-intro/gsi-examples/online-discussion-forums/.

MERLOT. (n.d.). Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.merlot.org/merlot/.

NWACCo. (n.d.). Ed Tech Deck. NWACCo. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.nwacco.org/about/.

Perez, K. M. (2020, September 8). Fostering a Sense of Belonging in STEM. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/09/08/encouraging-sense-belonging-among-underrepresented-students-key-their-success-stem.

Prud’homme-Généreux, A. (2021, March 29). 21 Ways to Structure an Online Discussion, Part 1 | Faculty Focus. Faculty Focus | Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/online-education/online-student-engagement/21-ways-to-structure-an-online-discussion-part-1/.

Purdue Writing Lab. (n.d.). Purdue OWL // Purdue Writing Lab. Purdue Writing Lab. Retrieved September 17, 2022, from https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/purdue_owl.html.

Reid, P. (n.d.). CAT Cross-ref to Goals. Google Docs. Retrieved July 7, 2022, from https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1AkMMP75OdeOL4PNjTYvuKaDBTRn2wqxDdBAQtjAuCCo/edit?usp=sharing&usp=embed_facebook.

Schrock, K. (n.d.). Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Everything. Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Everything. Retrieved September 17, 2022, from https://www.schrockguide.net/.

Skinner, N. F. (2015, October 22). Dropping Scores: The Case for Hope. Faculty Focus. http://info.magnapubs.com/blog/articles/educational-assessment/dropping-scores-the-case-for-hope/.

Spangler, S. (n.d.). Flipping Assessment: Making Assessment a Learning Experience. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from http://info.magnapubs.com/blog/articles/educational-assessment/flipping-assessment-making-assessment-a-learning-experience/.

Supplemental Instruction. (n.d.). Active Learning Strategy Cards. DePaul University. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://resources.depaul.edu/teaching-commons/teaching-guides/learning-activities/Documents/Strategy%20Cards%207.25.16%20MASTER.pdf.

Teaching Techniques for Higher Education. (n.d.). The K. Patricia Cross Academy. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://kpcrossacademy.org/downloads/.

The Problem-Based Learning Clearinghouse. (n.d.). Institute for Transforming University Education, University of Delaware. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://www.itue.udel.edu:443/pbl/problems.

Weimer, M. (2012, November 19). Deep Learning vs. Surface Learning: Getting Students to Understand the Difference. The Teaching Professor. https://www.teachingprofessor.com/topics/for-those-who-teach/deep-learning-vs-surface-learning-getting-students-to-understand-the-difference/.