C. Teaching Practices

C11. Group Work

- Group Work

- IDI & Group Work

- References

Group Work

Many Students Don’t Like Group Work

There are three basic reasons that some students don’t like group work. Some students feel it is more time consuming than working alone. Others feel that not all group members contribute equally or some members derail group discussions. Students with a duelist mindset may resist group learning, problem-based learning, flipped classrooms, etc. because they believe they are wasting their time listening to non-experts.

To help students with group work, Arkoudis et al. (2013, p. 230) recommend that you include statements in your syllabus to support groups:

- “Setting clear expectations about peer interaction;

- Respecting and acknowledging diverse perspectives;

- Assisting students to develop rules regarding interaction within their group;

- Informing students how engaging with diverse learning strategies will assist their learning;

- Providing groupwork resources for students.”

- Defining clearly how communities of learners will be assessed (including peer feedback) (Arkoudis et al., 2013, p. 234).

- Including a statement about the value of groups diversity in the syllabus (Arkoudis et al., 2013, p.230).

Rationale For Group Work

Group work has been shown to strengthen all students’ understanding of material and also complete quality work. Kirschner et al. (2018, p. 217) propose that collaborative learning can support learning because each team member brings different working memory information to the group. “By having multiple working memories working together on the same task, the effective capacity of the multiple working memories may be increased due to a collective working memory effect.”

Vygotsky (1978) found that students, working together, reached a deeper level of learning than when working alone. According to Stamper (2022)“Learning from others opens up students’ minds to new perspectives, enhances their ability to learn new lessons, and allows them to rethink their beliefs and form their own opinions.”

Fink shares two major course purposes which specifically apply to groups:

- Become more informed and thoughtful citizens: Developing our readiness to participate in civic activities at one or more levels, for example, the local community, state government, national government, and international advocate groups

- Preparing us for the world of work: Developing the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for being effective in one or more professional fields

Group Work for Diversity

Gordon, et al. (2019, p. 1) report that businesses are expecting employees to be able to work effectively with diverse colleagues. Padilla-Angulo et al. (2019) report that diversity is sought after in business team members and executives. However, Hall et al. (2011) found that positive interactions with diverse peers is a learned behavior.

For many students, group work provides a less stressful class environment and increases their sense of belonging. “Belonging is not merely an abstract concept, but is tied to how resources such as study groups, dialogue with instructors and scholarly reputation are allocated” (Perez, 2020). In addition, group work often lessens the competitive atmosphere in many courses.

Smolcic & Arends (2017, p.60) report that although the students at first found it uncomfortable, matching international and national students in learning groups increased student introspection and awareness of their own and other cultural differences.

Forming Groups

Please note that some institutes have policies about how instructors group students.

Many researchers recommend that students should not select their own team members as they will often create homogenous groups (Arkoudis et al., 2013, p.229; Smolcic & Arends, 2017). “Create groups … that mitigate or eliminate tokenism” (Goldwasser & Hubbard, 2019). Match international and national students in study pairs or groups. Smolcic & Arends (2017) report that although the students at first found it uncomfortable, it increased student introspection and awareness of their own and other cultural differences.

- Check with your IT department to see if group management software is available (such as CATME or The Team Formation Tool). If no software is available, ask students to complete a short questionnaire to identify their skills (provide a list but offer a fill-in-the-blank). This can then be used to group students to provide each group with a good skill mix (R. Reid & Garson, 2016, p. 27; TEAM-UP, 2020). “For instance, “how comfortable are you with image editing programs?”, “how comfortable are you in a leadership role?”, “how comfortable are you managing a project?”, “how comfortable are you writing applications for the web?” (Pursel, n.d.)

- Assign students to groups. Explain “When you work in the real world, you work with whoever you have to work with, and you don’t choose your buddies” (Holland, 2019, p.313).

- Loes et al. (2018, p.937) suggest groups of no more than 6 students.

- Reid & Garson (2016) describe an activity they used to provide instructors some input for forming diverse groups:

On one piece, they (students) listed six characteristics of a successful group, for example, respectful of members’ ideas, sharing the workload, showing up on time, and so on. On the second piece of paper, they were asked to write down four strengths that they brought to the group, such as research skills, presentation skills, writing skills, and so on. They were also given an opportunity to write down the name of one person in the class with whom they would like to work. This allowed the students some agency in choosing a group mate while still allowing the instructor the freedom to strategically create the most optimal mix of cultures and skills for the majority of the groups. Interestingly, students often did not identify another person to work with and were content to let the instructor form the groups.

Assessing Group Work

Make sure you tell students how they will be assessed on each group activity. You can grade students in group work based on their intermediate and end product and/or how well they functioned within the group. Pursel (n.d.) lists the following options for grades:

- A single group grade

- Grade adjusted based on peer reviews

- Individual grades

- A group grade and an individual grade

On long-term projects, although you can wait until the end of a project to provide feedback on how team members did, providing formative assessments during the project may be beneficial. These can be products, drafts, or status updates on the activity and/or peer assessments.

Peer Assessment

“If peer-reporting is used, the average of reported values from multiple team-members should be considered” (University of Washington, n.d.). Although you can wait until the end of a project to receive feedback on how team members did, providing formative assessments during the project may be beneficial.

Several peer assessments for teams are available. The following examples might be useful:

- Pursel, B. (n.d.). Working with Student Teams. Retrieved June 30, 2017, from https://sites.psu.edu/schreyer/

- Team effectiveness diagnostic. (n.d.). London Leadership Academy. Retrieved March 27, 2021, from https://www.londonleadershipacademy.nhs.uk/leadershiptoolkit/leading-teams-and-change/leading-teams

- University of Washington. (n.d.). Group Collaboration Guide. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://canvas.uw.edu/courses/1076981/modules

Short-Term Group Work

Students may be grouped for a long-term project or for less formal work. For the latter, the groups can be the same all semester or you can change the group members. Using discussion groups or chats, many of these can be synchronous or asynchronous, classroom or distance Some common activities include:

- Discussions: after students have completed some readings, they can be grouped to discuss questions you specify.

- Short projects: Ask groups to brainstorm a specific topic or mindmap connections between concepts.

- Jigsaw activities: small groups brainstorm a topic then new groups are formed with 1 member from each of the previous groups to discuss their findings.

- Think-Pair-Share: individually, students think of answers to a specific question, then pair up to discuss together, then either group with others to share or share in a full=-class discussion.

You can modify many other activities to provide paired and grouped activities. See the section on Learning Strategies (XX) for some additional suggestions.

During the group activity, pay attention to how the groups are progressing. Restad (2013) remarks that it is important to participate along with the class:

Be ready to give a five-minute flash lecture to address a confusion you discovered while circulating through the teams. Challenge one team to defend its conclusions against those of another. Build on the class’s insights by making a well-timed observation or summation that furthers the conversation.

Introducing the Activity

Although you may provide an excellent written description, students also need to hear about it and have an opportunity to ask questions.

- Do not read the instructions.

- Start with a brief description of the activity and its purpose, giving the course outcomes that are involved.

- You may note that as soon as you mention a group activity, students will start looking for others to form groups. Tell them early if you have assigned groups. Explain “When you work in the real world, you work with whoever you have to work with, and you don’t choose your buddies” (Holland, 2019, p.313).

- Provide a synopsis of the activity.

- Discuss formats for the final product (is it a simple read-out, a butcher-paper list, etc.).

- Discuss in-class time and out-of-class time expectations.

- Ask students if they have questions.

- After the students have started the activity, check with each team for questions and problems.

Introducing the Activity – Inclusion Strategies

If you have many group activities planned, consider a presentation on inclusion issues and strategies. You may need to remind students of these before each activity. The following suggestions are specifically about member inclusion.

- Discuss the importance of diversity and inclusivity (defining both) in group activities.

- Provide information about implicit bias such as assumed roles that may occur based on group’s cultural and/or gender make-up. Introduce strategies for removing the bias (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020). For example, is it assumed that the female in the group will provide emotional support or take a serving role? Are students with heavy accents overtalked or ignored?

- Ask students to be aware of ‘tokenism’ – that is, watch for signs that a person is being asked to speak for their entire age, culture, race, religion, disability, etc.

- Ask students to pay attention to microaggressions within the group: These may include excluding students from discussions and activities, and stigmatizing students.

- Provide strategies for students to help overcome biases and microaggressions such as developing group rules, limiting talking time per person, breaking into smaller groups at points and coming back to the larger group with ideas, etc.

- Discuss cognitive dissonance and the ‘Shimon Peres solution.’ (See Chapter A8)

Long-Term Group Work

Group work assignments have major advantages over individual assignments and are frequently defined as a high-impact practice as research has shown that students learn from each other. Group assignments can range from requiring students to group together to do homework or take quizzes or grouping students for long-term projects.

Because group work is a frequently used method to encourage active and transformative learning, some suggestions are included here.

Activity Description for Long-Term Group Work

When writing up the activity description for students, consider these:

- Dates of group work in class.

- Due dates for status reports, drafts, peer feedback, specific deliverables, etc.

- Course outcomes and objectives this supports.

- Any expectations that students change roles during the project. (This is a common instructional technique targeted at helping students experience different group roles. For this, you can provide a description of various common group roles.)

- Any out of class group work expectations.

- The advantages of group work based on research.

- Recommended (or required) steps to complete the task (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020)

- Dates of check-ins such as a reference list and outline, first draft, final, status updates, etc.

- Dates of peer evaluations and a peer evaluation rubric. Consider using these after a few group meetings to ensure the groups are functioning well.

- Why you are assigning groups rather than allowing them to choose group members.

- A worksheet for each student to fill in member names and contact methods (at least two methods for each student).

- How learners will be assessed (including how other group member’s input impacts individual grades).

- Information about group processes, including typical group roles and group stages (ex: forming, storming norming, performing).

- Information about project management and processes.

- Dates when students should change roles (to give each member an opportunity to understand and practice each role).

- Think through whether you will allow students to ‘fire’ group members and, if so, under what conditions. Determine what will happen to ‘fired’ students (can they form their own group, do they need to do the work on their own…). Include this information in the activity description to ensure students are clear on your decisions.

You may also want to review the PBLWorks Essential Project Design Elements Checklist.

Introducing the Activity

Although your written activity description may be excellent, students also need to hear about it and have an opportunity to ask questions.

- Do not read the instructions to the students.

- Start with a brief description of the activity and its purpose, giving the course outcomes that are involved.

- You may note that as soon as you mention a group activity, students will start looking for others to form groups. Tell them early that you have assigned groups. Explain “When you work in the real world, you work with whoever you have to work with, and you don’t choose your buddies” (Holland, 2019, p.313).

- Provide a synopsis of the activity.

- Discuss formats for the final product (will it require a report or presentation, or can the groups select a reporting format?).

- Discuss in-class time and out-of-class time expectations.

- Provide a timeline, including peer assessments and check-in dates and times.

- Ask students if they have questions.

- Break the students into their groups to discuss the assignment. Many times students will not have a clear idea of the project results, so ask them to discuss what they think the assignment is and ask them to develop at least three questions for you.

- Ask them to develop their group contract (see below). Ask students to discuss their communication styles and how these can be used to strengthen the group.

- Bring the class back together and have each group ask their questions.

- As you answer questions, take a note of common concerns to determine if you need to address these by discussing them with the class, making changes to the assignment, clarifying something, etc.

Introducing the Activity – Inclusion Strategies

On long-term group work, it is important that all members are contributing. To help with this, consider discussing inclusion issues and strategies near the beginning of the work. The following suggestions are specifically about member inclusion.

- Discuss the importance of diversity and inclusivity (defining both) in group activities.

- Provide information about implicit bias such as assumed roles that may occur based on group’s cultural and/or gender make-up. Introduce strategies for removing the bias (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020). For example, is it assumed that the female in the group will provide emotional support or take a serving role? Are students with heavy accents overtalked or ignored?

- Ask students to be aware of ‘tokenism’ – that is, watch for signs that a person is being asked to speak for their entire age, culture, race, religion, disability, etc.

- Ask students to pay attention to microaggressions within the group: These may include excluding students from discussions and activities, and stigmatizing students.

- Provide strategies for students to help overcome biases and microaggressions such as developing group rules, limiting talking time per person, breaking into smaller groups at points and coming back to the larger group with ideas, etc.

- Discuss cognitive dissonance and the ‘Shimon Peres solution.’ (See Chapter A8)

- Especially for larger assignments, have check-ins such as peer reviews.

Group Contracts

Group contracts can be developed by each group to ensure they all have a common understanding of their responsibilities to the group. You can either recommend or require group contracts and provide a recommended list of contents. Many examples are available online under a ‘college group contract’ search, including a course on collaboration available from the University of Washington (n.d.).

Contracts might include:

- What is the group purpose?

- Names and primary contact information for all group members

- If a member asks a question, when is expected answer (48 hours, 3 days, next meeting…)?

- When will the group meet? Where and for how long?

- How soon do you need to notify the group that you cannot attend meeting?

- What are consequences of not making a meeting?

- How will we ensure that all members are able to participate (consider both inclusivity and role comfort)?

- Who is filling each group member role?

- What is the process used to remove a group member (if allowed)? What steps must the group take first?

- Where will we share documents?

- How will we know when a section of the project is completed (is it by majority vote, group leader decision, etc.)?

- What is the group action plan and who is participating in each step? Who is responsible for final product?

- Under what conditions can the group ‘fire’ a member?

- What does the group do if a member doesn’t complete assigned work?

- Under what conditions does the group ask the instructor for help?

- With assignment?

- With member conflicts and issues?

Voting Students Out of a Group

At times, a group may find member(s) who are not supporting the group and/or causing disruptions. As an instructor, you should determine if a group can vote-out members. If you decide this is ok:

- You also need to decide what to do with voted-out members. Options include allowing them to do the work on their own, allowing them to ask another group to take them in, and/or allowing voted-out students to form another group.

- You need to decide when a student can be voted out. Because an early stage of group work is storming, you may require that students work together for a set time frame before allowing them to vote-out members.

Ongoing Management

If you know a project manager, you may want to request that they present to your class. This can be over several sessions, scheduled to fit the project’s progress, such as:

- At beginning of assignment, stakeholder and project definition, what is and is not included, etc.

- Project breakdown into tasks, assignments, dependencies, scheduling, etc.

- Risk and mitigation/management identification

- Monitoring and controlling progress, communicating with stakeholders

- Closing the project

Each of these can be a short presentation of the concept followed by students working on their projects.

Handouts for Students

You may want to provide students with information about managing groups such as group stages (so they don’t feel like they aren’t making progress) and/or group member roles. The following sources might be useful:

Group Work

Forming Groups | Introduction to Communication. (n.d.). Retrieved April 14, 2021, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/introductiontocommunication/chapter/forming-groups/.

Groups Roles | Introduction to Communication. (n.d.). Retrieved April 14, 2021, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/introductiontocommunication/chapter/groups-roles/.

University of Minnesota. (2016a). 13.2 Small Group Development. In Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition, 2016. This edition adapted from a work originally produced in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that it not receive attribution. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/13-2-small-group-development/.

University of Minnesota. (2016b). 13.3 Small Group Dynamics. In Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition, 2016. This edition adapted from a work originally produced in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that it not receive attribution. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/13-3-small-group-dynamics/.

University of Minnesota. (2016b). 14.2 Group Member Roles. In Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition, 2016. This edition adapted from a work originally produced in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that it not receive attribution. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/14-2-group-member-roles/.

Project Work

For group project management technologies, refer students to the following articles:

Benz, M. (n.d.). The Best FREE Google Project Management Apps Out There. Business 2 Community. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from https://www.business2community.com/strategy/the-best-free-google-project-management-apps-out-there-02177836.

Esposito, E. (2020, September 29). The best free project management software in 2020. Zapier. https://zapier.com/blog/free-project-management-software/.

If you do not have forms used within your discipline, review the free forms available from PBLWorks (https://my.pblworks.org/resources). This includes many resources for you on how to design a project assignment, but also 12 Student Handouts to help students manage their projects. Although these are designed for K-12 projects, they pretty much work for any HE term-long group work as well. If these do not seem appropriate for you, a Google search on “free project management forms for students” will provide you with many options.

Technology For Group Work

Student groups might need technology to meet, manage the group, and share documents and notes. The LMS probably has the ability to provide virtual group meeting spaces. Your institution may provide students with shared drives such as OneDrive, GoogleDrive, or DropBox. If these are not available, Google provides free sharable documents, including spreadsheets and presentations.

The following pages list apps which might be useful.

- University of Washington. (n.d.). Group Collaboration Guide. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://canvas.uw.edu/courses/1076981/modules.

- Mason, J. (2021, March 19). The 9 Best Teach Tools For Collaboration. We Are Teachers. https://www.weareteachers.com/student-collaboration-tech-tools/.

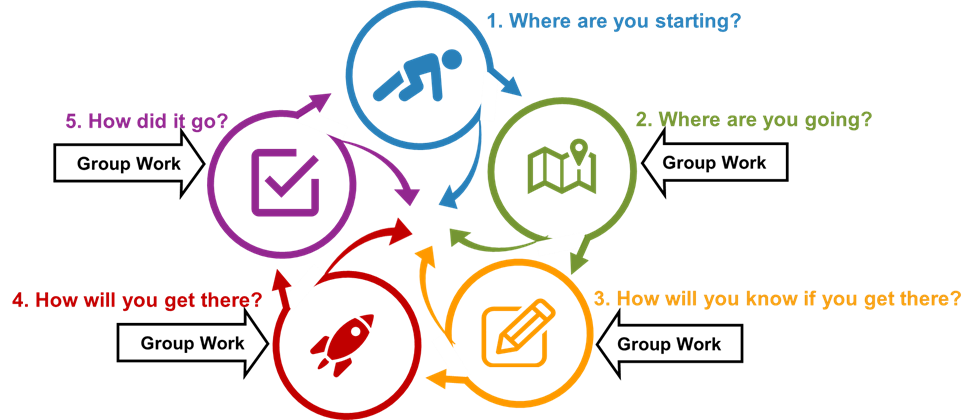

IDI & Group Work

The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from group work in the IDI model:

Step 2. Where are You Going?

2.1 Write Learning Outcomes & Objectives

- Consider adding a statement to your syllabus about expectations for peer interaction.

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- Develop a grading method for group work, including rubrics.

- Develop a peer evaluation for group work if desired.

- For long-term group work:

- Check if a group management app is available.

- Determine group formations.

- Determine if you will allow voting students out of groups and repercussions.

- If you are inviting a guest speaker, schedule it and add to class calendar.

- Add information to the syllabus about grading group work and any major projects.

- Determine how you will provide long-term group work information to students (include in syllabus, hand-out in class, both?)

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.1 Develop & Teach Course

- For all short-term group work, determine details on management, such as how you will introduce the activity, watch progress, assess, and close.

- Review ‘Introducing the Activity’ and ‘Introducing the Activity – Inclusion Strategies‘ for short-term or long-term group work.

- Identify all hand-outs for the activity and determine when you will provide these (potentially add some to syllabus).

Introducing the Activity

- Do not read the instructions to the students.

- Start with a brief description of the activity and its purpose, giving the course outcomes that are involved.

- You may note that as soon as you mention a group activity, students will start looking for others to form groups. Tell them early if you have assigned groups. Explain “When you work in the real world, you work with whoever you have to work with, and you don’t choose your buddies” (Holland, 2019, p.313).

- Provide a synopsis of the activity.

- Discuss formats for the final product (is it a simple read-out, a butcher-paper list, etc.).

- Discuss in-class time and out-of-class time expectations.

- Ask students if they have questions.

- After the students have started the activity, check with each team for questions and problems.

Introducing the Activity

- If you have many group activities planned, consider a presentation on inclusion issues and strategies. You may need to remind students of these before each activity. The following suggestions are specifically about member inclusion.

- Discuss the importance of diversity and inclusivity (defining both) in group activities.

- Provide information about implicit bias such as assumed roles that may occur based on group’s cultural and/or gender make-up. Introduce strategies for removing the bias (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, 2020). For example, is it assumed that the female in the group will provide emotional support or take a serving role? Are students with heavy accents overtalked or ignored?

- Ask students to be aware of ‘tokenism’ – that is, watch for signs that a person is being asked to speak for their entire age, culture, race, religion, disability, etc.

- Ask students to pay attention to microaggressions within the group: These may include excluding students from discussions and activities, and stigmatizing students.

- Provide strategies for students to help overcome biases and microaggressions such as developing group rules, limiting talking time per person, breaking into smaller groups at points and coming back to the larger group with ideas, etc.

- Discuss cognitive dissonance and the ‘Shimon Peres solution.’ (See Chapter A8)

Long-Term Group Work

- Discuss how group work is beneficial to student learning.

- Ask students to review the grading rubric and add to it.

- Ask groups to develop a group contract. Provide examples or an outline.

- Provide information on group roles, stages, and project management.

- Observe group progress and intervene as necessary.

- Provide formative assessment of both the group interaction and the end-product.

4.2 Assess Students

- Use the grading rubric, observations of the groups, and peer evaluations to assess students.

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Use the class outline to note how various activities worked.

References

Arkoudis, S., Watty, K., Baik, C., Yu, X., Borland, H., Chang, S., Lang, I., Lang, J., & Pearce, A. (2013). Finding common ground: Enhancing interaction between domestic and international students in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(3), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.719156.

Benz, M. (n.d.). The Best FREE Google Project Management Apps Out There. Business 2 Community. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from https://www.business2community.com/strategy/the-best-free-google-project-management-apps-out-there-02177836.

Esposito, E. (2020, September 29). The best free project management software in 2020. Zapier. https://zapier.com/blog/free-project-management-software/.

Forming Groups | Introduction to Communication. (n.d.). Retrieved April 14, 2021, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/introductiontocommunication/chapter/forming-groups/.

Gordon, S. R., Yough, M., Finney, E. A., Haken, A., & Mathew, S. (2019). Learning about Diversity Issues: Examining the Relationship between University Initiatives and Faculty Practices in Preparing Global-Ready Students. Educational Considerations, 45(1). https://eric.ed.gov/?q=Diversity+in+the+classroom+better+student+learning&ff1=dtySince_2016&ff2=eduHigher+Education&pg=2&id=EJ1219107.

Groups Roles | Introduction to Communication. (n.d.). Retrieved April 14, 2021, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/introductiontocommunication/chapter/groups-roles/.

Hall, W. D., Cabrera, A. F., & Milem, J. F. (2011). A Tale of Two Groups: Differences Between Minority Students and Non-Minority Students in their Predispositions to and Engagement with Diverse Peers at a Predominantly White Institution. Research in Higher Education, 52(4), 420–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-010-9201-4.

Holland, D. G. (2019). The Struggle to Belong and Thrive. In E. Seymour & A.-B. Hunter (Eds.), Talking about Leaving Revisited (pp. 277–327). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2_9.

Mason, J. (2021, March 19). The 9 Best Teach Tools For Collaboration. We Are Teachers. https://www.weareteachers.com/student-collaboration-tech-tools/.

PBLWorks (https://my.pblworks.org/resources).

Pursel, B. (n.d.). Working with Student Teams. Retrieved June 30, 2017, from https://sites.psu.edu/schreyer/.

Reid, R., & Garson, K. (2016). Rethinking Multicultural Group Work as Intercultural Learning—Robin Reid, Kyra Garson, 2017. Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(3), 195–212.

Restad, P. (2013, July 22). “I Don’t Like This One Little Bit.” Tales from a Flipped Classroom. Faculty Focus. http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-with-technology-articles/i-dont-like-this-one-little-bit-tales-from-a-flipped-classroom/.

Smolcic, E., & Arends, J. (2017). Building Teacher Interculturality: Student Partnerships in University Classrooms. Teacher Education Quarterly, 44(4), 51–73.

Stamper, B. (2022). 4 Misconceptions of Online Learning. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2022/5/4-misconceptions-of-online-learning.

Team effectiveness diagnostic. (n.d.). London Leadership Academy. Retrieved March 27, 2021, from https://www.londonleadershipacademy.nhs.uk/leadershiptoolkit/leading-teams-and-change/leading-teams.

University of Minnesota. (2016a). 13.2 Small Group Development. In Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition, 2016. This edition adapted from a work originally produced in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that it not receive attribution. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/13-2-small-group-development/.

University of Minnesota. (2016b). 14.2 Group Member Roles. In Communication in the Real World. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing edition, 2016. This edition adapted from a work originally produced in 2013 by a publisher who has requested that it not receive attribution. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/chapter/14-2-group-member-roles/.

University of Washington. (n.d.). Group Collaboration Guide. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://canvas.uw.edu/courses/1076981/modules.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.; Revised ed. edition). Harvard Univ Pr.