B. Learning & Instructional Design Principles

B3. Design Principles

- Design Principles

- IDI & Design Principles

- Course Structure: The How, When, & Where of Learning

- Temporal

- Spatial

- Pedagogical

- Selecting a Structure: Temporal, Spatial, and Pedagogical

- Common Pedagogical Models and Transformative Learning

- Table 1: Common Pedagogical Approaches/Learning Models

- Table 2: Common Activities Based on Pedagogical Approach/Model

- IDI & Learning Models

- A. Models Using Transformative Pedagogies

- B. Models Which Are Active With An Online Focus

- C. Models Which Are Active Traditionally Offered in a Classroom

- D. Models Not Traditionally Considered Active with a Combination of Online & Classroom

- E. Models Not Traditionally Considered Active

- References

Design Principles

Backward Design

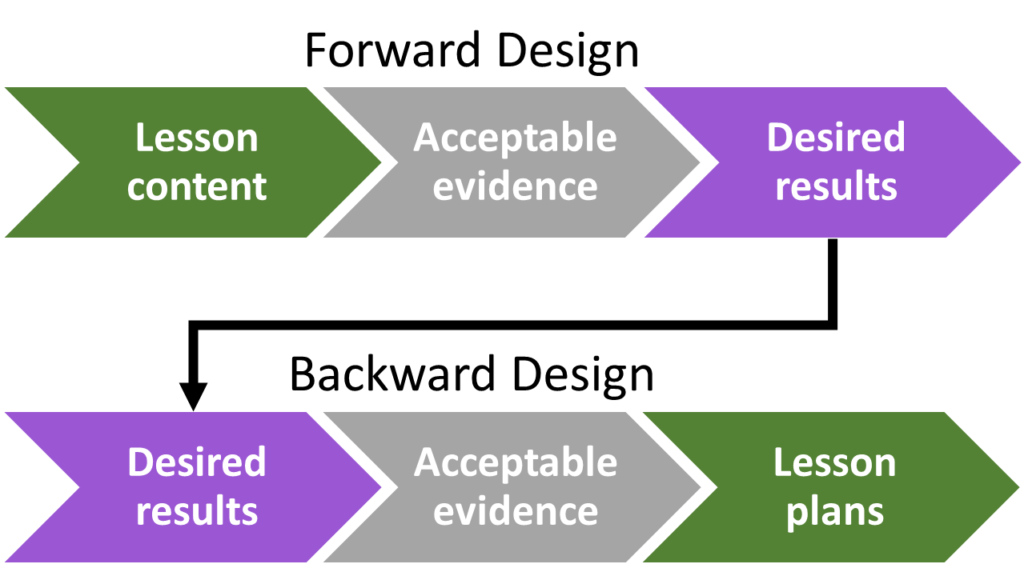

Often, an instructor is tempted to identify what they want to teach and develop courses and classes based on this. This is referred to as forward design (Figure 1).

Instead, ID starts with the end result: what students should know, be able to do, and what attitudes they should have at the end of the course (SKAs). From these SKAs, you can develop learning outcomes and then objectives, followed by assessments and activities. This is often referred to as backward design, a term usually credited to Wiggins & McTighe who wrote Understanding by Design (2006).

Figure 1: Forward and Backward Design

IDI & Design Principles

The IDI model used in this workbook provides a basic sequential format, but is targeted at higher education rather than business, industry, and the military. Therefore, the analysis phase is focused on program goals, other desired outcomes, and student demographics. The steps and sub-steps in the IDI models are:

“Where are You Starting?”

- Review Course Requirements

- Identify Student Learning Characteristics

“Where are You Going?”

- Write Learning Outcomes & Objectives

- Finalize learning model

“How Will You Know If You Get There?”

- Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- Develop Instruments to Evaluate the Course

“How Will You Get There?”

- Develop & Teach Course

- Assess Students

“How Did It Go?”

- Evaluate course

- Identify changes

The IDI model also tries to capture the non-linear aspects that you will naturally use. For example, as course designers identify learning outcomes (Step 2), they may think of specific activities (Step 3 and 4) that would be appropriate and during the teaching of a session (Step 4), changes to the assessments (Step 3), and/or future course sessions (Step 5) may be identified. And, because teaching is very complex and requires a good starting plan, teaching and ID require an ability to shift gears as needed. These shifts are based on how the students are grasping the material but may also occur due to national and international news and policies (such as a pandemic and DoE’s requirements for instructor contact in distance courses). Users of the IDI model should not feel a rigid, mandatory procedure is required – the brain doesn’t necessarily work that way and stuff happens.

Details for the IDI model are included in the workbook.

For more about ADDIE and other ID models, see the introduction to ID.

Course Structure: The How, When, & Where of Learning

The structure of a course lies in where, when, and how the course is presented. This can impact the design of activities, assessments, sense of community, etc. For this reason, learning timing, location, and model are a part of the design of a course and must be determined in the “Where are You Starting” and “Where are You Going” stages of IDI course design.

The Workbook step 2 walks through selection of the course structure.

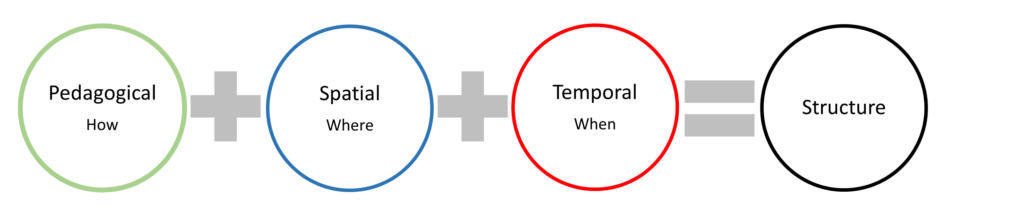

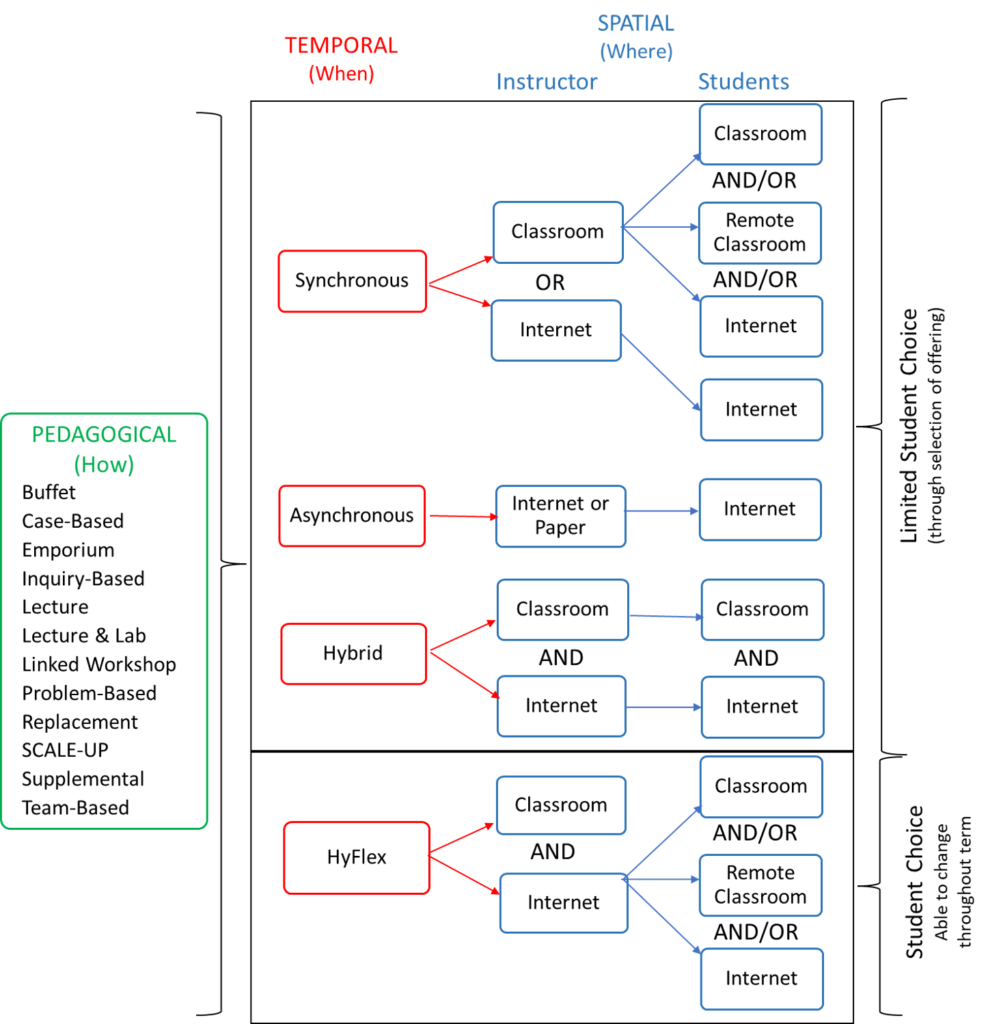

In this workbook, we use the term Temporal Pattern to refer to the WHEN of learning, Spatial Pattern to refer to WHERE, and Pedagogical to refer to HOW – the type of design. See Figure 2 for an illustration of how these relate to each other.

Figure 2: Basic Course Structure

Temporal

We currently have 4 temporal options:

- synchronous,

- asynchronous,

- hybrid, and

- HyFlex.

Synchronous courses require that all participants (students and instructors) be available at the same scheduled time, either online, in multiple classrooms, and/or other locations (such as from home). Asynchronous courses do not require participants to be available at the same time and are usually online (although some paper-based learning does still exist). Hybrid courses have some synchronous and some asynchronous components. HyFlex is a relatively new format where students can choose to participate in any segment of learning either synchronously or asynchronously and change as they need. In HyFlex, all components offered synchronously are also offered asynchronously.

During the pandemic we saw a new format referred to as emergency remote (ERT) – most institutions required that all courses were asynchronous and online. This should not be confused with typical asynchronous online courses due to the amount of preparation, training, and reflection time instructors had available to put their courses online.

Support for Asynchronous Students

Asynchronous students will possibly require additional support from you. Because they do not have the same connection to you, the course, other students, and, potentially, your institution, you will need to be in personal contact with them regularly (note that this is required by DoE now). For more on this, see the section in Chapter B2, Online Good Teaching Principles.

Spatial

Spatial refers to the Where of the structure. We have basically 3 spatial options:

- Local Classroom,

- Remote Classroom (Remote classroom that is linked to instructor’s classroom), and/or

- Online (Remote, but not in a formal classroom).

Modes are basically classroom or online. However, some courses also offer distance classroom experiences via either remote classrooms or home-based synchronous classes. If you are using a room set up specifically for synchronous classroom teaching, make sure you know how to use all the equipment and have technical support contact information handy.

Pedagogical

We currently have about 12 basic pedagogical approaches.

- Buffet

- Case-Based

- Emporium

- Inquiry-Based

- Lecture

- Lecture & Lab

- Linked Workshop

- Problem-Based

- Replacement

- SCALE-UP

- Supplemental Team-Based

(Note that these terms are used differently by different organizations.) These refer to the teaching and learning philosophy and approach used to provide learning. Although about 12 pedagogical approaches are documented here, note that every instructor puts a twist on the approach.

Flipped and HyFlex are Not Pedagogical Models

Flipped Courses

In an effort to unify the definition of Flipped Learning, The Flipped Learning Network (“Definition of Flipped Learning,” n.d.) states: “Flipped Learning is a pedagogical approach in which direct instruction moves from the group learning space to the individual learning space, and the resulting group space is transformed into a dynamic, interactive learning environment where the educator guides students as they apply concepts and engage creatively in the subject matter.”

Under this definition, flipped is temporally hybrid, and the classroom portion is structured on the pedagogical approach selected. The purpose is to provide students with learning support (usually from other students, TAs, or the instructor). The group sessions may be formatted as individual assignment time and/or as grouped activities (such as cases and projects), and, therefore, the models listed as transformative pedagogy and SCALE-UP are almost always flipped.

Flipped Courses Resources

Berrett, D. (2012, February 19). How ‘Flipping’ the Classroom Can Improve the Traditional Lecture. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/How-Flipping-the-Classroom/130857/

Brame, C. (n.d.). Flipping the Classroom. Retrieved from

http://cft.vanderbilt.edu/teaching-guides/teaching-activities/flipping-the-classroom/

Caldarera, J. (2012, April 20). Flipped Classroom – Best Practices. Retrieved from

http://prezi.com/-yrrp4lyodap/flipped-classrom-best-practices/

Demski, J. (2013, January 23). 6 Expert Tips for Flipping the Classroom. Retrieved from http://campustechnology.com/articles/2013/01/23/6-expert-tips-for-flipping-the-classroom.aspx

Enfield, J. (2013). Looking at the Impact of the Flipped Classroom Model of Instruction on Undergraduate Multimedia Students at CSUN. Techtrends: Linking Research & Practice To Improve Learning, 57(6), 14-27.

Hanover Research (2013, October 15). Best Practices for the Flipped Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.hanoverresearch.com/insights/best-practices-for-the-flipped-classroom/?i=k-12-education

Hill, C. (2013, August 26). The benefits of Flipping Your Classroom. Retrieved from

http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/instructional-design/the-benefits-of-flipping-your-classroom/

Lorenzetti, J. (2013, October 4). How to Create Assessments for the Flipped Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/instructional-design/how-to-create-assessments-for-the-flipped-classroom/

Makice, K. (2012, April 13).Flipping the Classroom Requires More than Video. Retrieved fromhttp://www.wired.com/geekdad/2012/04/flipping-the-classroom/

McGivney-Burelle, J. & Xue, F. (2013). Flipping Calculus. PRIMUS: Problems, Resources, and Issues in Mathematics Undergraduate Studies, 23:5,477-486. DOI: 10.1080/10511970.2012.757571

Miller, A. (2012, February 24). Five Best Practices for the Flipped Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.edutopia.org/blog/flipped-classroom-best-practices-andrew-miller

Restad, P. (2013, July 22). “I Don’t Like This One Little Bit” Tales from a Flipped Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-with-technology-articles/i-dont-like-this-one-little-bit-tales-from-a-flipped-classroom/

Schell, J. (2013, April 16). The 2 Most Powerful Flipped Classroom Tips I Have Learned So Far. Retrieved from http://blog.peerinstruction.net/2013/04/16/the-2-most-powerful-flipped-classroom-tips-i-have-learned-so-far/

Schell, J. (2012, March 2). Student Resistance to Flipped Classrooms. Retrieved from http://blog.peerinstruction.net/2012/03/02/peer-instruction-and-student-resistance-to-interactive-pedagogy/

Schneider, B., Blikstein, P., & Pea, R. (2013, August 5). The Flipped, Flipped Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.stanforddaily.com/2013/08/05/the-flipped-flipped-classroom/

SkillsTutor (n.d). Improve the Education of Every Student with a Flipped Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.skillstutor.com/hmh/op/edit/Home/Best_Practices/flipped_classroom

Strayer, J. (2012). How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation, and task orientation. Learning Environments Research, 15(2), 171-193. doi:10.1007/s10984-012-9108-4

Ullman, E. (2013, April 23). Tools and Tips for the Flipped Classroom. Retrieved from http://www.techlearning.com/features/0039/tools-and-tips-for-the-flipped-classroom/53725

Selecting a Structure: Temporal, Spatial, and Pedagogical

The Wordbook Step 2.2 may help you identify your course structure. In some circumstances, the temporal and spatial aspects of a course may be defined by the program, department, or institution. For example, many institutions have fully online nursing programs (all instructors and students are online and all learning is available asynchronously). Another example: many science courses are departmentally required to be flipped (hybrid where the instruction/content dissemination occurs outside of the classroom and active learning occurs in the classroom). However, in others, you may have an opportunity to select the temporal, spatial, and/or pedagogical aspect of your course structure. Your TLC, IDs, and ETs should be able to talk with you about how each aspect will impact your model and further choices, such as activities. Changing structure can often result in additional work to re-think and redevelop parts of the course, so you should consult with others early in the IDI process.

Figure 3 illustrates details on course structure.

Distance Learning: Online, Hybrid, HyFlex, and ERT

“To claim that certain teaching cannot be done remotely is to ignore the experience and innovative abilities of the university teaching staff” (Vutukuru, 2020). Online, hybrid and HyFlex terms refer to the timing of delivery, not the pedagogical aspect. Many universities provide instructional designers and/or educational technologists who support instructors in developing online, HyFlex, and hybrid courses.

With changes in technology and COVID-forced changes in physical and virtual teaching environments, models of learning traditionally considered as classroom-based (such as SCALE-UP and Case-Based Learning) can be migrated to an online environment. These may initially take more design and development thought than the classroom versions. However, the physical location of students does not necessarily dictate the pedagogy (How).

Fully Online

A fully online course makes use of technologies such as an LMS (such as Moodle, Canvas, Blackboard, and D2L). A fully online course may be synchronous (all students and instructors are online at the same time and communicating ‘live’) or asynchronous (students may access learning materials such as videos and recordings, discussion groups, and readings at any time). A fully online course can, these days, be arranged as any of the pedagogical approaches and involve learning that is non-active, active, or transformative.

Effective 7/2021, US DoE regulations stated that distance education courses must “support regular and substantive interaction between the students and the instructor, synchronously or asynchronously.” The DoE further stated “We do not consider interaction that is wholly optional or initiated primarily by the student to be regular and substantive interaction between students and instructors.” For further information on how this might apply to you, see Regular & Substantive Interaction – OSCQR – SUNY Online Course Quality Review Rubric, n.d.)

With the introduction of new technologies targeted specifically at higher education, almost every day it is becoming easier to teach online providing quality as good as – or in some cases better than – classroom-based courses. It may require rethinking approaches, but many instructors have developed an online model that includes active learning and a ‘flipped’ approach. Thousands of research articles have been published about methods for effective online learning and teaching.

Hybrid Teaching

An approach that is increasing in use, partially because of the 2020-2022 pandemic, is the hybrid approach. Hybrid refers to teaching both online and in the classroom for the same course offering. Variations may include:

- Students must attend in person for specific sessions and online for other specific sessions.

- The instructor offers the class session synchronously, with students selecting where they attend.

- Synchronous classroom attendance AND online asynchronous lectures are required (this is frequently the approach for a flipped course).

HyFlex Teaching

HyFlex is designed to give students choices in where and when they learn. “Students choose between attending and participating in class sessions in a traditional classroom (or lecture hall) setting or online environment. Online participation is available in synchronous or asynchronous mode; sometimes both and sometimes in only one online mode” (Beatty, 2019). While hybrid offers some synchronous and some asynchronous learning and some online and some face-to-face learning, this is determined by the instructor. In HyFlex, all material is available synchronously and asynchronously and all synchronous material is available online or face-to-face. This lets students choose the option of attending sessions in the classroom, participating online, or doing both. Students can change their spatial and temporal pattern of attendance weekly or by topic, according to need or preference. Courses built on the HyFlex model help to break down the boundary between the virtual classroom and the physical one. By allowing students access to both platforms, the design encourages discussion threads to move from one platform to the other (Milman et al., n.d.). Students frequently take the same final assessment, regardless of the chosen path through the material. Models like HyFlex, which present multiple paths through course content, may work particularly well for courses where students arrive with varying levels of expertise or background in the subject matter. As such, HyFlex defines the temporal and spatial portions of the structure, and may limit the pedagogical approaches chosen by the instructor.

This format initially places more pressure on the instructor and support team as they need to carefully consider every aspect of the course and how it can be offered in all modes and formats. For example, because of the student choices, collaborative learning activities may need to be redesigned.

Resources

- HyFlex World. (n.d.). HyFlex World. Retrieved September 24, 2022, from https://hyflexworld.wordpress.com/

- Milman, N., Irvine, V., Kelly, K., Miller, J., & Saichaie, K. (2020). 7 Things You Should Know About the HyFlex Course Model. EDUCAUSE Learning Initiative, 2.

- Penrod, J. (2022). Staying Relevant: The Importance of Incorporating HyFlex Learning into Higher Education Strategy. EDUCAUSE. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2022/3/staying-relevant-the-importance-of-incorporating-hyflex-learning-into-higher-education-strategy

- Pressley, J. P. (2022, March 1). Explaining the Difference Between HyFlex and Hybrid Teaching Models. EdTech. https://edtechmagazine.com/higher/article/2022/03/hyflex-hybrid-teaching-models-whats-the-difference-eperfcon

- Raman, R., Sullivan, N., Zolbanin, H., Nittala, L., Hvalshagen, M., & Allen, R. (2021). Practical Tips for HyFlex Undergraduate Teaching During a Pandemic. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 48(1). https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.04828

Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT)

ERT was frequently implemented during the 2020-2022 pandemic when classrooms were shut-down. Because these courses were transferred to an online environment rapidly and frequently by instructors with no previous online teaching experience, the quality of ERT courses should not be confused with normal online courses.

Labs for Online and Hybrid Courses

Until recently, one of the most difficult parts of creating fully online courses and programs has been in courses with a lab component. How can you provide a chemistry or surgical lab at home that provides hands-on experiences?

If you have a lab component in your course, consider options for providing a similar experience via distance.

- Older (2020) reports that Gibb recorded every lab and developed worksheets for students to complete while watching them.

- Boston University built engineering course lab kits and mailed them to each student (Vutukuru, 2020). They conducted the labs via synchronous online meetings, with instructors in each virtual lab. “To substitute expensive equipment like oscilloscopes, students programmed their Arduino microcontrollers. This creative solution introduced students to microcontrollers earlier than usual — typically microcontroller use is taught at a later stage in the undergraduate engineering curriculum. … In fact, the students were more engaged and eager to learn and build circuits in the comfort of their own homes than when on the campus” (Vutukuru, 2020).

- Some companies provide science kits for labs such as chemistry. Vandermolen (2016) lists some of these on the OLC webpage: The Science Lab Makeover: 6 Resources to Consider for Your Online Science Lab [Online Learning Consortium]. OLC Insights. https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/science-lab-makeover-6-resources-consider-online-science-lab/

Organizations Supporting High-Quality Online Courses

Your institute may have IDs, ETs, or TLC specialists who can help you with online course design. Check with your department administrative team or your TLC.

To help ensure that online courses have a high level of quality, several organizations have developed rubrics that you can use. The two most commonly used are Quality Matters (QM) and Online Learning Consortium (OLC).

The OLC provides a suite of online quality checking tools including (Descriptions taken from OLC Quality Scorecard – Improve the Quality of Online Learning & Teaching, n.d.):

- Administration of Online Programs: Launched in 2011, this Scorecard has been used by over 400 institutions to measure the effectiveness of their online learning programs. Handbook, rubric, and interactive dashboard available. Learn more and access this Scorecard. This Scorecard is also available in Spanish.

- Blended Learning Programs: Launched in 2015, this Scorecard focuses on best practices for implementing successful hybrid and blended learning programs. Handbook, rubric, and interactive dashboard available.

- Quality Course Teaching and Instructional Practice: This comprehensive scorecard can be used for an in-depth review to validate instructional practices as compared to quality standards identified by our panel of experts. The scorecard is available for use as a full scorecard or through our four breakout scorecards: Course Fundamentals, Learning Foundations, Faculty Engagement and Student Engagement. .

- Digital Courseware Instructional Practice: This solution has a focus on teaching using digital courseware.

- Quality Scorecard for Online Student Support: The latest addition to the OLC Quality Scorecard Suite is designed to assist in the identification of gaps in services and provides a pathway to improve support for online students. The scorecard facilitates an introspective look at 11 key areas of an institution. This scorecard was developed from a joint initiative with the State University System of Florida (SUSF) and the Florida College System (FCS).

Reference List

- Online Learning Consortium: https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/

- Quality Matters (QM) – https://www.qualitymatters.org/

Common Pedagogical Models and Transformative Learning

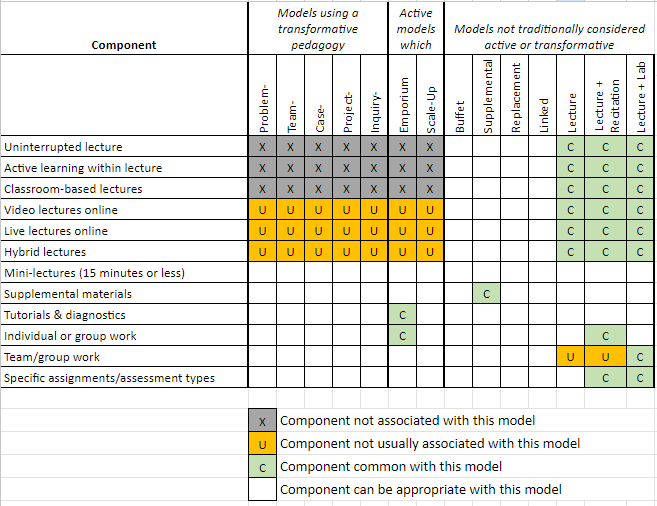

Learning models can be compared in multiple ways. Many courses use a combination of activities, such as lecture-based with some projects, but the predominant pedagogical approach is still lecture. Different authors have defined these models in different ways. For example, some define flipped and SCALE-UP as project- or case- based, while others define flipped as a course where all assignments are completed in the sessions while the lectures are viewed outside of the sessions. Tables 1 and 2 compare some common learning models based on student engagement with the learning material.

Table 1: Common Pedagogical Approaches/Learning Models

| A. Models using a transformative pedagogy (Classroom and/or Online)1 | Active models which could be transformative | Models not traditionally considered active | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. Active with an online focus | C. Active with focus on grouped students (Classroom and/or Online)4 | D. Combination of online & classroom | E. Traditional (Classroom and/or Online) | |

| Problem-Based Inquiry-Based Policy- and/or Law-Based3 Team-Based Case-Based Project-Based | Emporium2 | SCALE-UP | Buffet2 Supplemental2 Replacement2 Linked2 | Lecture Lecture + Recitation Lecture + Lab |

| Space requirements | ||||

| Usually require a classroom with either movable chairs and tables or a room specifically designated as active or transformative OR Students must have good internet access at home or in specified classrooms. | Students must have good internet access at home or in specified classrooms. | Requires a classroom with specific round tables AND Students must have good internet access at home or in specified classrooms. | Students must have good internet access at home or in specified classrooms. | Typically, no special requirements for either online or classroom, with exception of lab. However, some activities may be impeded by classroom set-up (ex.: group work in a fixed-seats room). |

| Footnotes: 1. Authors have classified transformative models in different ways, sometimes with Inquiry-Based as a major model and Project-, Case-, and others as fitting within it, other times with Project-Based as the parent, etc. Whichever way they are grouped, there are differences and similarities between them. 2. These are models identified by the National Center for Academic Transformation (NCAT). NCAT defines transformative models as those that 1) involve information technology, 2) improve student learning, and 3) reduce costs. Transformative teaching structures do not necessarily relate to transformative learning. 3. Policy and/or Law-Based Learning is a subset of Inquiry-Based Learning where the focus for students is investigating why a policy or law was created. 4. SCALE-UP courses usually use a combination of Category A models such as team- and project- learning. | ||||

Table 2: Common Activities Based on Pedagogical Approach/Model

(View table as readable Google sheet in new tab)

IDI & Learning Models

Your structure will impact the types of assignments and assessments you can use. For example, the emporium model doesn’t lend itself to group projects and case-based doesn’t lend itself to individualized attention as much as the emporium model.

As mentioned, your course may use one of these models, but incorporate additional features from another model.

A. Models Using Transformative Pedagogies

Typically, these involve collaborative group work.

NOTE: PBL can mean either problem-based learning or project-based learning. Both are described below.

Problem-Based Learning (PBL)

After being presented with a problem by the instructor, students work in groups to brainstorm ideas, identify what they know about the problem, what they don’t know but must learn in order to solve the problem, develop an action plan for research, and discuss the topics and concepts researched, eventually coming to some agreement on the best resolution. PBL develops students’ abilities to define problems, research and evaluate information, and develop solutions to problems.

Problem– and inquiry-based learning activities have a flexible format but typically follow a pattern of diagnosis and evaluation of a challenge or problem. The students would be asked to:

- define or identify the problem or challenge,

- diagnose potential reasons for this problem,

- brainstorm and evaluate alternative solutions or options, and

- choose the most appropriate solution and justify the reason for their choice.

Articles

- Problem-based Learning – Faculty Focus. (n.d.). Faculty Focus. Retrieved September 8, 2013, from http://www.facultyfocus.com/tag/problem-based-learning/.

- Stanford University. (2001, WINTER). Problem-Based Learning. SPEAKING OF TEACHING. Retrieved from https://stanford.box.com/shared/static/0y42jxd1leptkqbm4ffe.pdf.

- Yadav, A., Subedi, D., Lundeberg, M. A., & Bunting, C. F. (2011). Problem-based Learning: Influence on Students’ Learning in an Electrical Engineering Course. Journal of Engineering Education, 100(2), 253–280. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.2011.tb00013.x.

Example Of Use

Case Study: Problem-Based Learning at University of Delaware. (n.d.). University of Delaware. Retrieved September 8, 2013, from http://www.udel.edu/inst/.

Inquiry-Based Learning

“Inquiry-based learning is a form of active learning that starts by posing questions, problems or scenarios. … The inquiry-based instruction is principally very closely related to the development and practice of thinking and problem solving skills” (“Inquiry-Based Learning,” 2021). Wabisabi Learning (Transformative Inquiry-Based Learning With the Wabisabi Inquiry Cycle, n.d.) defines the Inquiry-Based Learning (IBL) model as a cycle: “The components of this cycle are the Global Concept, the Essential Question, and the 4 Cs [Curious, Connect, Communicate, and Create].”

“Inquiry-based learning is an unorthodox method of learning which incorporates active participation of students by involving them in posing questions and bringing real-life experiences to them. The basis of this method is to channelize the thought process of the students through queries and help them in ‘how to think’ instead of ‘what to think’” (Inquiry-Based Learning, n.d.).

Policy & Law-Based Learning

Policy-based and/or Law-based learning involves students investigating a policy – how it was made, why, and the values underlying the policy. This may be a focus of an Inquiry-based learning course.

Articles

- For more about Inquiry-based learning, see https://www.edutopia.org/topic/inquiry-based-learning.

- 5 Examples of Inquiry Based Learning. (n.d.). Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://www.masterofartsinteaching.net/lists/5-examples-of-inquiry-based-learning/

- Edelson, D. C., Gordin, D. N., & Pea, R. D. (1999). Addressing the Challenges of Inquiry-Based Learning Through Technology and Curriculum Design. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 8(3 & 4), 60.

- Ernst, D., Hodge, A., & Yoshinobu, S. (2017). What Is Inquiry-Based Learning? Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 64, 570–574. https://doi.org/10.1090/noti1536.

- Inquiry-Based Learning. (n.d.). Santa Ana College. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://www.sac.edu/AcademicAffairs/TracDat/Pages/Inquiry-Based-Learning-.aspx.

- Inquiry-based learning. (2021). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Inquiry-based_learning&oldid=1000031291.

- Inquiry-Based Learning. (n.d.). Edutopia. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://www.edutopia.org/topic/inquiry-based-learning.

- Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., de Jong, T., van Riesen, S. A. N., Kamp, E. T., Manoli, C. C., Zacharia, Z. C., & Tsourlidaki, E. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: Definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review, 14, 47–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003.

- Transformative Inquiry-Based Learning With the Wabisabi Inquiry Cycle. (n.d.). Wabisabi Learning. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://wabisabilearning.com/blogs/inquiry/wabisabi-inquiry-cycle.

Team-Based Learning (TBL)

Although many approaches utilize teams, TBL applies specific procedures for developing high performance learning teams. Michaelsen & Sweet (2008) developed a team-based learning approach that uses a specific sequence of individual work, group work, followed by immediate feedback. TBL emphasizes problem solving and interpersonal skills. SCALE-UP (now called Student-Centered Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies) is another model that leverages team learning but includes online work (see the SCALE-UP model description below).

Articles

- Restad, P. (2013, July 22). “I Don’t Like This One Little Bit.” Tales from a Flipped Classroom. Faculty Focus. Retrieved September 8, 2013, from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-with-technology-articles/i-dont-like-this-one-little-bit-tales-from-a-flipped-classroom/.

- Team-Based Learning. (2018, November 6). Center for Advancing Teaching and Learning Through Research. https://learning.northeastern.edu/team-based-learning from https://learning.northeastern.edu/team-based-learning/ (Team-Based Learning, 2018).

Case Studies

- Team-Based Learning Collaborative – Home. (n.d.). Retrieved September 8, 2013, from http://www.teambasedlearning.org/.

- Michaelsen, Larry K. & Sweet, Michael. (2008). The Essential Elements of Team-Based Learning. Team-Based learning: Small-Group learning’s next big step, no. 116. Retrieved from http://www.csusm.edu/iits/ids/documents/active-learning/active%20learning/Team-based%20Learning%20michaelsen.pdf.

Case-Based Learning (CBL)

Cases are typically complex problems written to stimulate classroom discussion and collaborative analysis. CBL involves the interactive, student-centered exploration of realistic and specific situations. As students consider problems from a perspective which requires analysis, they strive to resolve questions that have no single right answer. Emphasizing the application of theory to practice, the use of contemporary cases can make subject matter more relevant.

Articles

- Stanford University. (1994, WINTER). Teaching with Case Studies. SPEAKING OF TEACHING. Retrieved from https://teachingcommons.stanford.edu/resources/teaching-resources/speaking-teaching-newsletter-archive.

- Wolter, B. H. K., Lundeberg, M. A., Bergland, M., Klyczek, K., Tosado, R., Toro, A., & White, C. D. (2013). Student Performance in a Multimedia Case-Study Environment. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 22(2), 215–225. doi:10.1007/s10956-012-9387-7.

Case Studies

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS). (n.d.). National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS). Retrieved September 8, 2013, from https://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/.

Project-Based Learning

“Project Based Learning is a teaching method in which students gain knowledge and skills by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to an authentic, engaging, and complex question, problem, or challenge” (What Is PBL?, n.d.). Project-based learning usually involves a group-work project which lasts the entire course term. Students may have some classroom lectures or out-of-class video lectures. The class-time is typically spent completing project work with the instructor providing just-in-time information about the project or about group work processes.

For example, a project-based IT course at Purdue University involved a full-semester project that focused on product innovation. Each course had over 50 students. The instructors assigned groups but allowed groups the option to ‘fire’ group members. During the semester, each group created a product then identified key aspects of product development, through to cost-determination, development, projected sales, and delivery (logistics).

Articles

- Jamal, A.-H., & Tilchin, O. (2016). Teachers’ Accountability for Adaptive Project-Based Learning. American Journal of Educational Research, 4(5), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-4-5-10.

- Start Me Up: Project-Learning Primers. (n.d.). Edutopia. Retrieved January 31, 2021, from https://www.edutopia.org/project-learning-online-resources.

- What is PBL? (n.d.). PBLWorks. Retrieved January 31, 2021, from https://www.pblworks.org/what-is-pbl.

B. Models Which Are Active With An Online Focus

Emporium

The emporium model replaces lectures with a learning resource center model featuring interactive computer software and on-demand personalized assistance. As defined by the National Center for Academic Transformation (National Center for Academic Transformation, n.d.), emporium:

- Eliminates all lectures and replaces them with a learning resource center model featuring interactive software and on-demand personalized assistance.

- Depends heavily on instructional software, including interactive tutorials, practice exercises, solutions to frequently asked questions, and online quizzes and tests.

- Allows students to choose what types of learning materials to use depending on their needs, and how quickly to work through the materials.

- Uses a staffing model that combines faculty, GTAs, peer tutors and others who respond directly to students’ specific needs and direct them to resources from which they can learn.

- May require a significant commitment of space and equipment.

- More than one course can be taught in an emporium, thus leveraging the initial investment.

While some courses (like Duolingo) may be completely online, using responsive software to correct and direct students, these are not necessarily Emporium. An important part of the emporium model is the availability of faculty, TAs and/or tutors to provide in-person assistance as needed.

Resources

- Watch: Kent State. (2011). “What students are saying about the Math Emporium.” Kent State University. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7OqBcXLEEIQ

video: (2:38) - Short description and case studies: http://www.thencat.org/PlanRes/R2R_Model_Emp.htm

- How to Structure a math emporium: http://www.thencat.org/R2R/AcadPrac/CM/MathEmpFAQ.htm

- New Pedagogical Models for Instruction in Mathematics (from Mathematical Modeling, Simulation, Visualization And E-Learning. 2008, 4, 361-371, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-540-74339-2_22)

- Link to list of case studies: http://www.thencat.org/PCR/model_emporium_all.htm

C. Models Which Are Active Traditionally Offered in a Classroom

SCALE-UP

SCALE-UP (Student-Centered Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies) spaces are “carefully designed to facilitate interactions between teams of students who work on short, interesting tasks…The basic idea is that you give students something interesting to investigate. While they work in teams, the instructor is free to roam around the classroom–asking questions, sending one team to help another, or asking why someone else got a different answer” (Scale-Up, n.d.).

Resources

Overview of the SCALE UP method of teaching…

Watch Old Dominion. (2009). “Old Dominion: SCALE UP-An Innovative Method for Teaching and Learning” Old Dominion. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ECDGy0wVPA

video: (3:36 mins)

Student and instructor reactions to SCALE-UP…

Watch Virginia Tech. (2011).“Virginia Tech: SCALE-UP Classroom.” Virginia Tech. Available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pUFud6MoHMo/

video: (2:41 mins)

SCALE-UP: About the project – https://sites.google.com/view/scale-up.

D. Models Not Traditionally Considered Active with a Combination of Online & Classroom

Buffet

The buffet model customizes the learning environment for each student based on background, learning preference, and academic/professional goals and offers students an assortment of individualized paths to reach the same learning outcomes. This usually involves developing individualized learning contracts with students. As defined by the National Center for Academic Transformation (National Center for Academic Transformation, n.d.), the buffet model:

- Customizes the learning environment for each student based on background, learning preference, and academic/professional goals.

- Requires an online assessment of student’s learning styles and study skills.

- Offers students an assortment of individualized paths to reach the same learning outcomes.

- Provides structure for students through an individualized learning contract which gives each student a detailed listing, module by module, of what needs to be accomplished, how this relates to the learning objectives, and when each part of the assignment must be completed.

- Includes an array of learning opportunities for students: lectures, individual discovery laboratories (in-class and Web-based), team/group discovery laboratories, individual and group review (both live and remote), small-group study sessions, videos, remedial/prerequisite/procedure training modules, contacts for study groups, oral and written presentations, active large-group problem-solving, homework assignments (GTA graded or self-graded), and individual and group projects.

- Uses an initial in-class orientation to provide information about the buffet structure, the course content, the learning contract, the purpose of the learning styles and study skills assessments, and the various ways that students might choose to learn the material.

- Modularizes course content.

- May allow students to earn variable credit based on how many modules they successfully complete by the close of the term, thus reducing the number of course repetitions. Students complete the remaining modules in the next term.

- Eliminates duplication of effort for faculty who divide tasks among themselves and target their efforts to developing and offering particular learning opportunities on the buffet.

- Enables the institution to evaluate the choices students make vis-a-vis the outcomes they achieve (e.g., if students do not attend lectures, the institution can eliminate lectures).

Resources

- NCAT write-up and case studies: http://www.thencat.org/PlanRes/R2R_Model_Buffet.htm

- Case study (2012): Missouri University of Science and Technology, Chemistry Available at: http://www.thencat.org/States/MO/Abstracts/MUST%20Chemistry_Abstract.html

- Link to list of case studies: http://www.thencat.org/PCR/model_buffet_all.htm

Supplemental

As defined by the National Center for Academic Transformation (n.d.): “The supplemental model retains the basic structure of the traditional course and a) supplements lectures and textbooks with technology-based, out-of-class activities, or b) also changes what goes on in the class by creating an active learning environment within a large lecture hall setting.”

Resources

- NCAT Write-up and case studies – https://www.thencat.org/PlanRes/R2R_Model_Sup.htm .

- Magoun, A.D., Hare, D., Saydam, A., Owens, C. & Smith, E. (2010). Assessing the Performance of College Algebra Using Modularity and Technology: A Two-Year Case Study of NCAT’s Supplemental Model. In D. Gibson & B. Dodge (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2010 (pp. 3471-3478). Chesapeake, VA: AACE. Retrieved from: http://www.editlib.org/p/33911/

- List of all NCAT Supplemental case studies: http://www.thencat.org/PCR/model_supp_all.htm

Examples That Add Out-Of-Class Activities and Do Not Change In-Class Activities

Example 1- University of New Mexico: General Psychology

- Students use a two-disc CD-ROM–which contains interactive activities, simulations, and movies–to review and augment text material.

- Students receive credit for completing four online proficiency quizzes each week and are encouraged to take the quizzes as many times as needed until they attain a perfect score. Only the highest scores count.

Example 2 – Carnegie Mellon University: Introductory Statistics

- An automated, intelligent tutoring system monitors students’ work during lab exercises, providing feedback when students pursue an unproductive path, and closely tracking and assessing a student’s acquisition of skills—in effect, providing an individual tutor for each student.

Examples That Add Out-Of-Class Activities and Change In-Class Activities

Example 1 – Spanish: – University of Massachusetts-Amherst: Introductory Biology

- Students review learning objectives, key concepts and supplemental material posted on the class Web site prior to class and complete online quizzes, which provide immediate feedback to students and data for instructors to assess student knowledge levels.

- During class, the instructors use a commercially available, interactive technology that compiles and displays students’ responses to problem-solving activities.

- Class time is divided into ten- to fifteen-minute lecture segments followed by sessions in which students work in small groups applying concepts to solve problems posed by the instructors.

- Instructors reduce class time spent on topics the students clearly understand, increase time on problem areas, and target individual students for remedial help.

Example 2 – English Composition: University of Colorado-Boulder: Introductory Astronomy

- A 200-student class meets twice a week in an auditorium.

- The first meeting focuses on an instructor overview of the week’s activities.

- About a dozen discussion questions are posted on the Web.

- Students meet for one hour in small learning teams of 10-15 students (supervised by undergraduate learning assistants) to prepare answers collaboratively and to carry out inquiry-based team projects.

- Teams post written answers to all questions.

- At the second class meeting, the instructor leads a discussion session, directing questions to the learning teams.

- The instructor has reviewed all posted answers prior to class and devotes class time to questions with dissonant answers among teams.

Replacement

As defined by the National Center for Academic Transformation (National Center for Academic Transformation, n.d.): “Reduces the number of in-class meetings and either replaces some in-class time with out-of-class, online, interactive learning activities or also makes significant changes in the remaining in-class meetings. Although in some ways this model resembles what is often referred to as a blended or hybrid model, the key differentiator is that the replacement model replaces in-class time with technology-based activities rather than simply adding technology-based activities to the traditional course” [emphasis added].

Resources

- NCAT Write-up – http://www.thencat.org/PlanRes/R2R_Model_Rep.htm

- Page of links to case studies: http://www.thencat.org/PCR/model_replace_all.htm

- Case study 1: http://www.thencat.org/PCR/R1/PSU/PSU_Overview.htm

- Case study 2: http://www.thencat.org/PCR/R3/TCC/TCC_Overview.htm

- Case study 3: http://www.thencat.org/PCR/R3/PoSU/PoSU_Overview.htm

Examples that Substitute Out-of-Class activities for Some In-Class Time and Do Not Change In-Class Activities

Example 1 – Penn State University: Elementary Statistics

- Reduce lectures from 3 to 1 per week (keeping 1 lecture the same) and change 2 recitation sections to 2 computer-studio labs, where students work individually and collaboratively on computer-based activities.

- Students are tested on assigned readings and homework using Readiness Assessment Tests (RATs) 5-7 times during the term for 30% of their grade.

- Students prepare outside of class by reading the textbook, completing assignments, and using Web-based resources. Students take the tests individually and then immediately in groups of four.

- RATs motivate students to keep on top of the course material and enable faculty to detect areas in which students are not grasping the concepts.

Example 2 – University of Wisconsin-Madison: General Chemistry

- Reduce lectures from 2 to 1 per week (keeping 1 lecture the same) and reduce discussion sessions from 2 to 1 per week.

- Substitute Web-based tutorial modules that lead students through a topic in 6 to 10 interactive pages.

- Then, a debriefing section includes questions that test whether the student has mastered the content.

- Diagnostic feedback points out why an incorrect response is not appropriate.

- Students can link directly from a difficult problem to additional tutorials that help them learn the concepts.

Examples that Substitute Out-of-Class Activities for Some In-Class Time and Change In-Class Activities

Example 1 – Spanish: University of Tennessee–Knoxville: Intermediate Spanish Transition

- Reduce class-meeting times from 3 to 2 per week.

- Move grammar instruction, practice exercises, testing, writing, and small-group activities focused on oral communication to the online environment.

- Use in-class time for developing and practicing oral communication skills.

Example 2 – English Composition: Tallahassee Community College: College Composition

- Reduce class-meeting times from 3 to 1 per week and substitute 2 workshops.

- Use online resources to provide diagnostic assessments resulting in individualized learning plans; interactive tutorials in grammar, mechanics, reading comprehension, and basic research skills; and discussion boards to facilitate the development of learning communities.

- Use in-class time to work on writing activities.

Linked Workshop

As defined by the National Center for Academic Transformation (National Center for Academic Transformation, n.d.), the Linked Workshop model:

- Retains the basic structure of the college-level course, particularly the number of class meetings.

- Replaces the remedial/developmental course with just-in-time workshops.

- Workshops are designed to remove deficiencies in core course competencies.

- Workshops consist of computer-based instruction, small-group activities, and test reviews to provide additional instruction on key concepts.

- Students are individually assigned software modules based on results of diagnostic assessments.

- Workshops are facilitated by students who have previously excelled in the core course and are trained and supervised by core course faculty.

- Workshop activities are just-in-time—i.e., designed so that students use the concepts during the next core course class session, which in turn helps them see the value of the workshops and motivates them to do the workshop activities.

Resources

- NCAT Write-up: http://www.thencat.org/PlanRes/R2R_Model_Linked.htm

- Case Study – Essentials of Writing: http://www.thencat.org/RedesignAlliance/C2R/R3/RU_Abstract.htm

- Case study – Math: http://www.thencat.org/States/TN/Abstracts/APSU%20Algebra_Abstract.htm

E. Models Not Traditionally Considered Active

Lecture, lecture and lab, and lecture and recitation courses are not traditionally considered active learning. These become active learning when the instructor uses active (or transformative) learning techniques and assignments to support students in higher-order thinking.

References

(This list does NOT include the pedagogical model references given above. They are, however, included in the Reference list)

Beatty, B. J. (2019). Values and Principles of Hybrid-Flexible Course Design. Hybrid-Flexible Course Design. https://edtechbooks.org/hyflex/hyflex_values.

Branch, R. M., & Dousay, T. A. (2015). Survey of instructional design models (5th ed.). AECT.

Definition of Flipped Learning. (n.d.). Flipped Learning Network Hub. Retrieved January 23, 2022, from https://flippedlearning.org/definition-of-flipped-learning/.

Gagné, R. M., Wager, W. W., Golas, K., & Keller, J. M. (2005). Principles of Instructional Design (5th ed). Thomson/Wadsworth.

Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2008). The Essential Elements of Team-Based Learning. Team-Based Learning: Small-Group Learning’s next Big Step, no. 116,. http://www.csusm.edu/iits/ids/documents/active-learning/active%20learning/Team-based%20Learning%20michaelsen.pdf.

Milman, N., Irvine, V., Kelly, K., Miller, J., & Saichaie, K. (n.d.). 7 Things You Should Know About the HyFlex Course Model. EDUCAUSE. Retrieved January 23, 2022, from https://library.educause.edu/resources/2020/7/7-things-you-should-know-about-the-hyflex-course-model.

National Center for Academic Transformation. (n.d.). A Summary of NCAT Program Outcomes. National Center for Academic Transformation (NCAT). Retrieved July 7, 2020, from https://www.thencat.org/Program_Outcomes_Summary.html.

Older, W. (2020). When COVID-19 Forced Him to Teach Online, This New York Tech Professor Got Creative. Inside Higher Ed. http://narratives.insidehighered.com/covid-19-forced-him-to-teach-online/.

Regular & Substantive Interaction – OSCQR – SUNY Online Course Quality Review Rubric. (n.d.). Retrieved January 21, 2022, from https://oscqr.suny.edu/rsi/.

Scale-up. (n.d.). SCALE-UP. Retrieved January 23, 2022, from https://sites.google.com/view/scale-up.

Transformative Inquiry-Based Learning With the Wabisabi Inquiry Cycle. (n.d.). Wabisabi Learning. Retrieved February 12, 2021, from https://wabisabilearning.com/blogs/inquiry/wabisabi-inquiry-cycle.

Vandermolen, J. (2016, August 29). The Science Lab Makeover: 6 Resources to Consider for Your Online Science Lab [Online Learning Consortium]. OLC Insights. https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/science-lab-makeover-6-resources-consider-online-science-lab/.

Vutukuru, M. (2020, August 5). Faulty Assumptions About Lab Teaching During COVID. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2020/08/05/engineering-instructor-disagrees-notion-lab-courses-cant-be-taught-effectively.

What is PBL? (n.d.). PBLWorks. Retrieved January 31, 2021, from https://www.pblworks.org/what-is-pbl

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2006). Understanding by design (Expanded 2nd ed). Pearson Education, Inc.