C. Teaching Practices

C6. Lectures

Lectures

Should You Lecture?

Listening to a lecture is successful learning for some students, but not most. Students who are motivated to learn the material may also reflect on the content after the lecture, identifying new applications and evaluating how well the applications work. During a lecture, they probably don’t have time to do this reflection as they are busy copying whatever you have on the board/slide.

“There is extensive evidence that active learning works better than a completely passive lecture” (Eddy et al., 2015, art. abstract). It is rare that straight lecturing is either active or transformative.

Lecturing induces passivity of thought, even in the best of students. They hurriedly take notes, but have little time to reflect on or question the material being jotted down… Lecturing doesn’t always encourage students to move beyond memorization of the information presented to analyzing and synthesizing ideas so that they can employ them in new ways (Center for Teaching and Learning, Stanford University Newsletter on Teaching, 1993).

However, “there is always the pressure to cover more and more material, so that activities involving students–activities taking up classroom time–seem wasteful” (Center for Teaching and Learning, Stanford University Newsletter on Teaching, 1993).

Content dissemination does not need to be provided during the class sessions and does not necessarily need to be provided in a lecture format. Instructors who are interested in providing their students with active and/or transformative learning experiences must balance the pressures of ‘covering’ material with the pressures of identifying, designing, and managing learning to meet active and/or transformative learning outcomes. Well-designed courses can accomplish both but must start with careful consideration of learning outcomes.

If You Must Lecture…

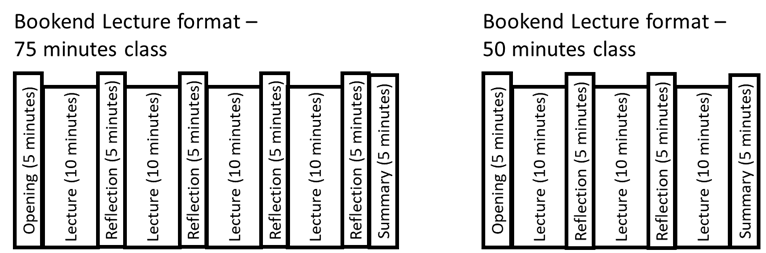

Lectures can be provided in-class or in videos. In either format, students will lose interest after about 10 minutes (see Extraneous Load in Chapter A8). To help students maintain interest and provide for deeper understanding, break up a lecture into about 10-minute chunks. You can use a ‘bookend’ format for these: 5 minutes opening, 10 minutes lecture, 5-minute reflective activity, 10-minute lecture, 5-minute reflective activity, etc. Note this applies to online courses and flipped courses as well as face-to-face. Visually, bookending looks like this figure:

The most common and relatively easy way to incorporate active learning during a lecture can be by asking questions. However, these questions may not produce the desired reflection:

- Usually, one student answers each question.

- Usually, only a handful of students answer any questions.

- Frequently, questions do not require more than regurgitation of the material, not significant added thinking.

- Often, instructors don’t provide incentives to answering questions.

- If tests are based on lower-order thinking skills (LOTS) – such as applying the same math formula to a new problem – they will not be encouraged to think about why this particular content is important.

Of course, some activities will take longer. The length of the activity should be weighed against the value – the probability of providing deeper understanding, and the value of the homework in providing content (using lectures to cover what was in the readings will quickly teach students they don’t need to do the readings).

Here are some guidelines from Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning (n.d.) that can help you structure an effective lecture (For details on each step, see original article available here: https://bokcenter.harvard.edu/lecturing):

- Define a problem

- Acknowledge the approaches not taken

- Lay out some possible scenarios for solving the problem

- Expose the data

- Deconstruct your expert “moves” – There is a critical mass of pedagogical research indicating that students learn well when their instructors make errors

- Don’t fear the dead end

- Obey the “Rule of Three.” in the typical 53-minute lecture, students can probably retain about three big concepts

The Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning (2012) also produced an article “Twenty Ways To Make Lectures More Participatory,” available here: https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/teachingLibrary/Lecturing/20-ways.pdf.

You can increase participation by:

- Ask students to write their answer then pair up (or other think-pair-share method)

- Using a polling program to collect student answers – this can then be displayed, and students grouped to discuss different answers

- Divide students into groups of 3 or 4 and assign each group different questions, then have them “jigsaw” – a member of each group joins with members of others and reviews their Q&As

- Divide the students into groups and assign a spokesperson to report back on their group discussion

Is the Activity Accomplishing What You Want?

Providing reflection time does not translate into either active or transformative learning. The reflection time needs to be carefully constructed to focus on specific learning objectives. Consider your content – will a five-minute reflection provide time and motivation for deeper thinking? Will this question-and-answer time lead to higher-order thinking skills (HOTS)?

Creating Lecture Videos

Most institutions can offer you support in developing videos, ranging from providing equipment or studios, to providing good practices. To find what your institution offers, contact your department administration, the TLC, or the IT help desk.

Accessibility – to ensure all students can use your videos, you will need to ensure you have closed captioning. Your Disability Services department and/or your IT department should be able to explain how to do this and provide access to the needed technology.

Encouraging viewing – Schell (2013) recommends short videos with a multiple choice or short answer quiz after each with a summative quiz at the end of a series of videos.

Interaction – Glantz, et al. (2021) report on a colleague who watches the videos with students in a synchronous session. The instructor then uses chat to answer questions as they come up and to provide additional explanations of the content as needed. You can also provide either an outline or discussion questions before each video to help students focus and frame the most important information.

Supplemental information – in addition to the standard videos, consider making additional videos to provide background, more depth, or extra information. You can make these optional. If you have different assignments for groups or individuals, they can also use these as reference materials.

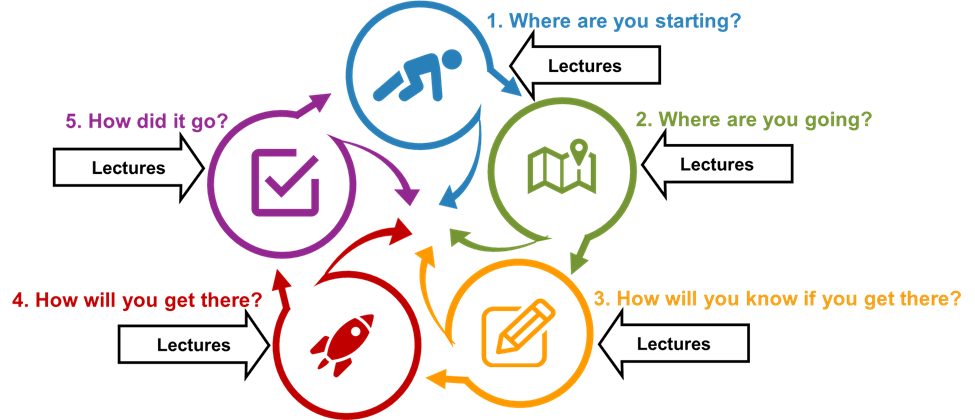

IDI & Lectures

The following describe actions you can take to use concepts from this chapter in the IDI model:

Step 1. Where are You Starting?

1.2 Identify Student Learning Characteristics

- Reflect on student demographics to identify if students have experience effectively listening to a lecture.

Step 2. Where are You Going?

2.1 Write Learning Outcomes & Objectives

- Identify the levels on Bloom’s Taxonomies for each outcome and objective. Ask “Will a lecture get the students there?”

2.2 Finalize Learning Model

- Consider how you can support students in learning from a lecture (If you lecture).

- Consider how you will fit subject content into selected course structure.

Step 3. How Will You Know If You Get There?

3.1 Develop Assessments & Rubrics

- Add content topics to the course instructor’s schedule.

- Consider how your lectures influence students’ motivation to listen to (or read) lecture material.

- Add appropriate content topics to students’ schedule in syllabus.

Step 4. How Will You Get There?

4.1 Develop & Teach Course

- Identify methods other than lectures to provide content.

- Identify how you will provide content in a lecture, and both maintain student interest and active learning.

- Create questions and activities that may lead to HOTS.

- Develop an outline of the content to identify sequencing.

- Develop your class outline to include the needed content and student reflection time.

- If you include lectures, either synchronous or asynchronous, use the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning (n.d.) format.

- Identify back-up approaches.

- Develop a handout, such as an outline or a copy of slides, for students to help them focus on important content.

- Pay attention to how students are reacting to the lecture and other activities. Switch approaches if needed.

Step 5. How Did It Go?

5.1 Evaluate Course Success

- Reflect on how well the class session worked to accomplish the learning outcomes and objectives.

References

Center for Teaching and Learning, Stanford University Newsletter on Teaching. (1993, FALL). Active Learning: Getting Students to Work and Think in the Classroom. Speaking of Teaching, 5(1). https://studylib.net/doc/8109039/getting-students-to-work-and-think-in-the-classroom.

Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Lecturing. Harvard University. Retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://bokcenter.harvard.edu/lecturing.

Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning. (2012). Twenty Ways to Make Lectures More Participatory. Harvard University |. https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/teachingLibrary/Lecturing/20-ways.pdf.

Eddy, S. L., Converse, M., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2015). PORTAAL: A Classroom Observation Tool Assessing Evidence-Based Teaching Practices for Active Learning in Large Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Classes. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(2), ar23. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.14-06-0095.

Glantz, E., Gamrat, C., Lenze, L., & Bardzell, J. (2021). Improved Student Engagement in Higher Education’s Next Normal. EDUCAUSE Review. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2021/3/improved-student-engagement-in-higher-educations-next-normal.

Schell, J. (2013, June 20). Two magical tools to get your students to do and learn from pre-class work in a flipped classroom. Turn to Your Neighbor: The Official Peer Instruction Blog. https://peerinstruction.wordpress.com/2013/06/20/two-magical-tools-to-get-your-students-to-do-and-learn-from-pre-class-work-in-a-flipped-classroom/.